Forever a Commodore

by Graham HaysVanderbilt helped Deeg Sezna chase a dream. Through the Deeg Sezna Scholarship, family and friends work to honor the 9/11 victim’s memory by giving others the same opportunity.

The events of Sept. 11, 2001, no longer form any part of the lived experience of most college students. The date remains part of the history young people learn. But for those born in the intervening years, the memories and emotions stemming from that day’s terrorist attacks won’t be their history.

For Vanderbilt golfers, however, Davis Grier “Deeg” Sezna Jr., BA’01, is part of their history—and always will be.

Those who knew Sezna best are committed to making sure that never changes. Twenty-two years after he was among the nearly 3,000 people killed in New York, Washington, D.C., and at a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, Sezna is still part of Vanderbilt golf’s present and future.

Deeg, as he was known by family and friends, didn’t play golf at Vanderbilt. But growing up in a family with deep roots in the sport, he was never more at home than walking a course, a bag of clubs slung over his shoulder. After his death at the World Trade Center’s South Tower, his parents, Davis and Gail Sezna, established a scholarship in his honor that became part of the fabric of one of the nation’s best college men’s golf programs. It has helped All-Americans and future professional golfers like Matthias Schwab and Will Gordon grow, on and off the course. For the past four years, it has helped All-American William Moll contribute to some of the program’s greatest successes, from back-to-back SEC championships to a Final Four appearance.

Now, after a gift from an anonymous alumnus of the Class of 2002 to Vanderbilt’s historic Dare to Grow campaign and dedicated to the children of Willy Sezna, Deeg’s surviving brother, those who knew him best hope to inspire others to complete the effort to fully endow what would be Vanderbilt’s first fully endowed golf scholarship.

A Vanderbilt Experience

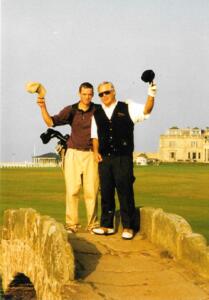

With a father who was the 1973 Delaware Open champion and worked in and around the sport for decades, Deeg grew up immersed in golf. Course locations and tee times shaped family vacations. They traveled to Scotland and played St. Andrews, where Davis Sr. is a member of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. When Deeg was 12, he tagged along one day for a round with his father, not expecting to play. When a member of the foursome had to drop out, one of the other players asked Deeg if he would fill in. The player? Longtime PGA professional Joe Inman. The course? New Jersey’s Pine Valley, often ranked as the best course in the world.

With a father who was the 1973 Delaware Open champion and worked in and around the sport for decades, Deeg grew up immersed in golf. Course locations and tee times shaped family vacations. They traveled to Scotland and played St. Andrews, where Davis Sr. is a member of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. When Deeg was 12, he tagged along one day for a round with his father, not expecting to play. When a member of the foursome had to drop out, one of the other players asked Deeg if he would fill in. The player? Longtime PGA professional Joe Inman. The course? New Jersey’s Pine Valley, often ranked as the best course in the world.

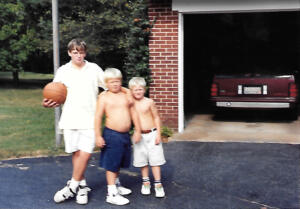

Growing up, Davis Sr. and his father played in the annual Leon “Pop” Sikes International Father-Son Golf Tournament at Atlantis Country Club in Florida. Almost from the moment Deeg was born, Davis Sr. counted down the years until they could continue the tradition. The moment finally arrived when Deeg was 11. The alternate-shot format can test the bonhomie of serious golfers, even family members. So, traveling to the tournament, dad reminded son that the trip was all in the name of fun. There was no reason to get upset if things went wrong.

The pair was still in contention on the second day when Deeg hit a picture-perfect drive, only for Davis Sr. to hit a poor shot into a bunker and derail their chances. Fuming at his own error, he stalked back to the golf cart and sat in brooding silence. Deeg tapped him on the knee. Son reminded dad that they were there to have fun.

“I needed my 11-year-old to straighten me up,” Davis recalled. “I chuckle about that to this day.

“I needed my 11-year-old to straighten me up,” Davis recalled. “I chuckle about that to this day.

“It was magical,” he said. “I always say family trips are terrific, but there’s nothing better than taking individual trips with your children. Those are the trips I remember the most.”

Deeg loved golf. He continued caddying even during summers at Vanderbilt. He was good enough to win local junior events and could have played collegiately at some level. But the other great passion of his youth drew him to Vanderbilt. Growing up in his family also meant growing up around business. His dad’s restaurant and golf ventures drew a steady stream of friends and golfing buddies from among the business elite—larger-than-life figures Deeg looked up to the same way his peers might have Tiger Woods or Ernie Els.

For someone who was reading The Wall Street Journal every morning as a high schooler, Vanderbilt offered the chance to chase dreams of a career in business—even if he wasn’t initially sure he was up to the challenge of the academic equivalent of the toughest par 5.

“He was just fascinated by the ins and outs of how business works and the history of people who were successful in the business world,” Gail Sezna recalled. “I think Vanderbilt was a great match for him. He got there and was just really impressed with the intelligence of the student body. I think he was maybe a little bit afraid of keeping up with it. But he did fine.”

Classmates recalled a carefree magnetism and a trademark baseball cap, worn backward with the bill curled in the style of the day. He didn’t put on airs, was quick with a dry wit and happy to engage with anyone, whether discussing golf, campus happenings or the world of Wall Street investing that he loved—and that eventually took him to New York.

“He was a bit of a border collie when it came to friends,” Davis said. “He was always embracing his friends. If there was punch, everyone would have a glass of punch before he did. He was a very thoughtful, intellectual, good person who was a great friend to many.”

After completing his degree, Deeg landed a job with Sandler O’Neill, a giant in the investment banking world that had offices high in the South Tower. It was a prestigious job—if one that came with long hours and intense pressure for a junior employee trying to make an impression. But it was where he wanted to be, the pressure every bit as welcome as it would be for a young golfer fighting for the lead on the final day of the Masters.

And so he was at work on the fateful Tuesday a week after Labor Day, getting an early start and wearing the suit that Sandler O’Neill boss Jimmy Dunne had already assured him he didn’t have to wear to meet the office’s business casual expectations.

The second plane hit the South Tower at 9:03 a.m., not quite 20 stories below the Sandler O’Neill offices and Deeg’s workspace. Approximately 40 percent of the firm’s employees died in the attack and ensuing tower collapse. Deeg was among them.

Just 22 years old, he had been on the job a matter of weeks.

Don’t Let the Devil Win

The scholarship was first awarded in 2006 to baseball student-manager Jason Cunningham, who continued to hold it after trying out and making the team as a pitcher the following year. After Cunningham graduated, and in consultation with the family, the scholarship found its permanent home with the men’s golf program. For Davis, it felt right. Not only had golf been central to the family’s life, but family friend and Vanderbilt Hall of Fame member and Toby Wilt, BE ’66, played an important part in encouraging Deeg to consider the school in the first place.

A two-time All-American, as well as an economics major recognized on multiple occasions on the SEC Academic Honor Roll, Moll is the current recipient.

Current scholarship recipient William Moll is a two-time All-American and SEC Academic Honor Roll honoree (Vanderbilt Athletics).

Proceeds from the annual Vandy Golf Day fundraiser at the Golf Club of Tennessee go toward maintaining the scholarship, but the recent anonymous gift is intended to inspire donations that will complete the endowment.

“It just shows the care level from our Vanderbilt community, that they see something that they appreciate and want to support with everything they have,” said Scott Limbaugh, Thomas F. Roush, M.D. and Family Men’s Head Golf Coach at Vanderbilt. “As this life goes on for all of us, you begin to understand and embrace what’s important to you. Deeg was near and dear to so many people at Vanderbilt. This is one of the ways the family has chosen to honor him, and we’re all extremely grateful that people continue to embrace his memory.”

Gail Sezna, too, had to continue after 9/11. She told herself she owed that to Deeg and Teddy—her youngest son who had died in a boating accident just a year before Deeg’s death. She told herself they wouldn’t want her to fade away or retreat from the world.

She found writing therapeutic and self-published a book. She purposefully limited printings and didn’t distribute it widely. But she will on occasion meet other parents who have lost children and share it with them, hoping it might be of use. It offers no easy answers or universal solutions. Those don’t exist. But you learn ways to manage, she said, like having a plan for what to do on the hardest days—birthdays, anniversaries and the like.

“It is sort of a bonding thing when you identify with other parents who have lost children,” she explained. “It’s a club you don’t really want to be in, but you can also be really helpful to other people.”

She has returned on multiple occasions to the National September 11 Memorial and Museum for the annual commemoration ceremony, joining other surviving family members in reading aloud the names of the victims. She has returned to Vanderbilt too. Deeg needed to complete a few final credits in the summer of 2001 and didn’t walk with his class during Commencement. Richard McCarty, at the time the dean of the College of Arts and Science and later Vanderbilt’s provost, invited her to attend a subsequent Commencement and walk with students in Deeg’s place.

Gail Sezna carries on. Because while there is pain in the memories of what you’ve lost, there is solace in knowing others remember the person you loved.

“The biggest fear you have when you lose your child is that they’ll be forgotten,” she said. “I think that’s universal.”

Invited to speak at the Sandler O’Neill memorial service held at Carnegie Hall about a month after the attacks, Davis told those assembled that even on their worst day, at their lowest ebb, they couldn’t let the devil win. They couldn’t stop moving forward.

“We all have met people who had losses—there are so many of them,” Davis said. “Deeg was one of 3,000. I feel for all of them. I feel even more for those who can’t find the energy to cope with it. It’s destroyed a lot of people. And why wouldn’t it? What do you really live for? To be proud of your kids and do your best to mentor them until they’re ready to go off to college and start learning life on their own. That’s what it’s all about. Life is not monolithic. It’s in chapters—one man in his time plays many parts, as Shakespeare said so beautifully.

“Deeg missed out on a lot of chapters. But through all of this, I’ve inherited many surrogate sons that we keep in touch with,” he said. “You know, I have my version of Deeg, but I love hearing their versions of him. Because 20 years later, we don’t miss him any less.”

A memory lives on

It was only after becoming men’s golf head coach at Vanderbilt in 2012 that Limbaugh learned Deeg’s story from women’s golf head coach Greg Allen and got to know the Sezna family. But like everyone who lived through that day, he can replay it in his mind more vividly than any number of far more recent events. Still a student at Huntingdon College in his native Alabama, Limbaugh recalls walking out of a marketing class, hearing talk begin to circulate and going to a computer lab in search of more information. For a time, he was even worried about his mom, who had recently departed for a trip to Washington, D.C., before learning she was still en route during the attacks.

Future generations won’t be able to call on those personal experiences, the bewilderment and visceral horror of that morning. It’s important to Limbaugh that they still understand what that day meant and what Deeg meant.

“They’re still aware of the significance of that day, for sure,” Limbaugh said. “The more time passes and the more that younger generations might become less aware of it, the more I want to talk about it. We’re always looking for opportunities to talk about life outside the game.”

For the parents who lost a son, the brother who lost a sibling and the friend who lost a kindred spirit, that’s what the scholarship represents. Through golf, the game he loved, it means Deeg is always a part of Vanderbilt, a school that, if all too briefly, helped make his dreams come true.

“If Deeg couldn’t be with us, then how do we make sure that he has (left) an indelible mark and memory in life?” Davis asked. “There couldn’t be anything better than Vanderbilt, especially Vanderbilt golf. I salute the administration for supporting men’s and women’s golf and their commitment to two great coaches, Greg Allen and Scott Limbaugh. Greg and Scott are driving toward national championships and not settling for less.

“Deeg would be so very proud to be remembered in that way.”

To help support the Deeg Sezna Scholarship, search “Deeg Sezna Scholarship” under “Other or Additional Allocations” on the Dare to Grow giving page.

About the Dare to Grow Campaign

Launched in Vanderbilt’s 150th year, Dare to Grow is a $3.2 billion comprehensive campaign, the most ambitious in university history. The campaign will succeed through three essential pathways—Destination Vanderbilt, Discovery Vanderbilt and One Vanderbilt—and by furthering the culture of belonging, innovation and collaboration that defines the Vanderbilt Way. Learn more at vu.edu/daretogrow.