Oct. 13, 2010

Commodore History Corner Archive

Commodore History Corner Archive

Sporting fans have enjoyed identifying their teams with a mascot. Vanderbilt has used “Mr. Commodore” as a visible mascot for decades. There have been times that Vanderbilt has used a dog to represent the university at sporting events.

In the fall of 1961, Toby Wilt arrived on the Vanderbilt campus to play football for the freshmen. Wilt took his family pet George, a basset hound, to Vanderbilt where they both were housed at the Sigma Chi House. Wilt’s girlfriend would take George to most football practices and home games.

It was during the Vanderbilt/Tennessee game on November 28, 1964 that George became a hero to Commodore fans. The Vols had a Tennessee walking horse that was ridden on the field during certain times of the game. At one point, George took off after the horse and chased him out of the stadium. The episode did not go unnoticed to the Vanderbilt fans in the stands that day.

The Tennessean reported on the incident:

- “George the basset hound, owned by Vandy halfback Toby Wilt whose fine run set up the only touchdown, inspired the Commodores before the opening kickoff. When Ebony Masterpiece, the Tennessee walking horse which has become the university’s mascot, pranced up and down the sidelines, George darted across the field and appeared to challenge him in animal jargon.”

Vanderbilt beat Tennessee that afternoon, 7-0 with Wilt’s 40-yard run from his halfback position setting up the winning score. “I don’t really know what George was thinking,” Wilt said. “My guess is that he had never seen a horse before and thought it was a big dog.”

A few weeks later a student organization selected George as the university’s official mascot for his courageous charge at the UT horse. George would have front row seats to Vanderbilt football and basketball games.

In the spring of 1965, the Metropolitan Health Department didn’t approve of the basset living in the fraternity house and was “officially” expelled. George was not altogether homeless and was taken care of by the students. The Council of Student Activities voted to build a house for George. The cost of the house was estimated at $2,000, which included carpeting and central heat and air. There was a debate on campus as to the exuberant expense for this doghouse. Eventually a regular doghouse was donated for George’s living quarters.

In November 1966, George chased an ice truck on the Vanderbilt campus and was killed. A funeral home donated a small casket and he was buried in a small plot just North of Dudley Field. Samantha, another basset hound, would replace George. She lasted until 1970 when it was decided that Samantha could not replace George. After Samantha’s master had graduated, students gave up on the idea of a basset hound mascot.

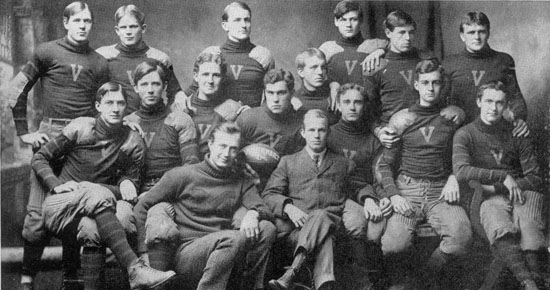

George was not the first canine to represent Vanderbilt football. The 1904 Commodore squad, led by first-year coach Dan McGugin, was proud of their bulldog mascot named Bull. But Bull did not appear to have the courage as George, and was improperly dismissed after an incident.

During Thanksgiving week in 1904, Vanderbilt was scheduled to play rival Sewanee in Nashville. During that week this headline appeared in the Tennessean:

- COMMODORES DON”T CARE IF HE NEVER COMES BACK

Secret Leaks Out–Bull, the Mascot, Whipped in a Fight With a Little Fox Terrier– Search For the Lost Dog Given Up.

This is the entire Tennessean story printed in 1904 on Bull the Vanderbilt football mascot:

- “Bull, the mascot, is still gone, and the search for him, strange as it may seem, has been given up. The members of the team say they don’t care if he never comes back.

“This sudden and seemingly inexplicable change in feeling has been brought about by reports derogatory to the character on the once greatly admired pup.

“It seems that a few hours before he disappeared Dan Blake decided to try the mettle of his charge in a scrimmage–not a football mix-up, but a fight with another dog. Bull was placed in a pen with a fox terrier of some fighting reputation. The former old Gold and Black mascot is not a full grown canine, sad it was thought it would be about an even proposition to buck him against a smaller fighting dog of reputation.

“When Bull was placed in the ring he positively, but respectfully, declined to fight. It was thought at first that this was because he did not want to fight an opponent of such comparatively small proportions. He did not want to chow another dog into doll rags without giving the animal a chance for his life. The fox terrier was not so backward and attacked Bull. In self-defense the bull pup was forced to fight, and he began with some very fierce growls and some terrible-looking grimaces. But it seems that growls and grimaces were is main stock in trade. They were soon changed to yelps and whines. Bull tucked his tail and the last few seconds of the scrimmages was a noble effort on the part of Bull to get as far away from the scene of trouble as possible.

“When the alleged fight was over Dan Blake fed the once highly prized animal back to the chapter house cellar, where he had his quarters, and unceremoniously dumped him into the coal chute.

“The next day Bull was gone. Whether the canine recognized his disgrace or not may never be known, but it is probable that he did, and that he greatly assisted in helping himself to disappear. In this case Phillips of Sewanee did not have as much to do with this incident as some might think.

“Dan Blake was the only member of the football team that knew anything about Bull’s disgrace. He thought it best not to tell the story and pledged two or three others who saw the imitation fight, to secrecy. The only thing he did was to announce the disappearance of Bull on the following afternoon when the squad came out for practice. It was noticed that Dan was not inclined to go into details, but it was thought this was because of his grief over the loss of the dog.

“The unusual way in which Dan seemed to view the matter, although he had extremely little to say, at last aroused the suspicions of other members of the team and they began to suspect that Dan was holding something back. This finally became a conviction and Dan was pressed to tell what it was. He held off for three or four days, but the pressure finally became too strong and he at last told, with tears in his eyes, the story of the disgrace of Bull.

“Such a sudden change of feeling as came over the football squad was a revelation. Word was passed down the line and was soon all over the campus to abandon the search. An official announcement was made before night that offers of a reward were withdrawn. If the dog is found and brought back anyway it is probable, thought nothing has been said about it, that he will be offered to Sewanee as a free-will gift.

“The Commodores are glad he is gone and they don’t want him back–that is officially speaking. Personally and privately, Dan Blake still has a kindly feeling for his old charge. He has already offered one or two little hints as excuses for Bull. Just after somebody had said something about Bull, Dan was heard to remark that a man shouldn’t expect to do much in the way of fighting until after he had at least a little experience or training.

“Whether he had the dog in mind or not he would not state. He was heard later to say that bulldogs did not become good fighters until they were fully grown. It is believed by some that Dan will finally be openly defending Bull, but at the present time the team, officially speaking, is ready to march the dog around the field on Thanksgiving Day as an emblem of what Sewanee will be after the game.”

Vanderbilt would defeat Sewanee 27-0 to cap an undefeated season. And did anyone think to check the bottom of the coal chute for poor ole Bull?

If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.

Dan Blake is top row, second from the left.