December 30, 2000: Shea Ralph (@Shea_UConn1) scores in traffic plus the foul in a 81-76 win over Tennessee pic.twitter.com/gOVSafuBXa

— Husky Highlights (@UConnHighlights) December 18, 2020

The Pioneer Behind Shea Ralph

by Graham HaysA mother and daughter’s basketball journey tells the story of a new era of equality

In April, Marsha Lake watched from a few feet away as her daughter was introduced as the sixth head coach in Vanderbilt women’s basketball history. The new coach, Shea Ralph, began her remarks that day by addressing her mother and stepfather directly: “I can’t thank you enough for the sacrifices you made for me that allowed me to sit in this chair.”

Ralph spoke not just as a daughter, but also as a representative of generations of women—the teammates she won championships alongside at UConn and the student-athletes she now leads at Vanderbilt.

Years before Lake began driving Ralph across the South to pursue her own basketball dreams, she arrived at the University of North Carolina as a member of the women’s basketball team. It was 1971—a year before the passage of Title IX, which barred schools receiving federal funds from discriminating based on gender.

Years before Vanderbilt could hire Ralph, a rising star coach sought by universities across the country, Lake was rebuked by UNC’s renowned college athletics director for speaking publicly about unequal training and playing conditions for women.

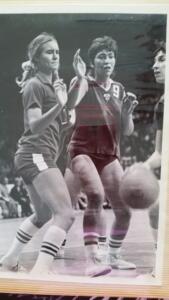

And years before Ralph’s generation helped set a standard for women who aspire and act to change the world through sports, Lake traveled to the Soviet Union as part of a team that represented the United States on the world stage for the first time in the Title IX era.

As the 50th anniversary of Title IX approaches, it’s important to remember the experiences of people like Lake, who made it possible for a new generation of women to push the boundaries of what’s possible in sports. Her legacy is evident, in ways large and small, as Ralph—a standout player and coach in her own right—mentors student-athletes who will lead the next generation. The mother and daughter’s basketball journeys are bookend stories of an era ushered in by legislation. And ultimately, they’re stories about what it takes to have a seat at the table.

“Look at what my daughter has achieved,” Lake says. “She made the game her life. She’s at the absolutely perfect school for her.

“I feel like because of what I went through during my time, maybe in some small way I paved the way for that to happen. In my little, teeny, small way. Because look at the benefits my daughter is reaping from what I fussed about when I was in college.”

From Dunn to Red Square

Lake grew up in Dunn, North Carolina, a small town south of Raleigh, playing a version of high school basketball specifically tailored to girls at the time. As Lake recalls, players were allowed three dribbles, and only two players on each team could play both ends of the court. (In other variations around the country, each team had three defensive players and three offensive players, and no players crossed midcourt).

The University of North Carolina established a varsity women’s basketball team not long before Lake arrived. But the university didn’t award its first athletic scholarship to a female student-athlete until after her junior year. (It went to a first-year student on the tennis team, although Lake went on to earn All-America honors as a senior.)

To help showcase the impact of Title IX at the time, a local television sportscaster interviewed her for a story on women’s sports at universities in the Research Triangle area. Lake explained that her team didn’t have enough basketballs for everyone at practice and that each player had only one heavy polyester uniform for home and road games. She discussed travel inequities, saying the women’s team wasn’t allowed to use the men’s bus, let alone take flights. They instead piled into station wagons with three rows of seats—Lake invariably getting carsick sitting in the rear-facing back row.

Not long after the story aired, she received a summons from then-North Carolina athletic director Homer Rice. None too pleased, Rice asked for an explanation. She told him she hadn’t said anything that wasn’t true. More basketballs eventually appeared. Her team even flew to a tournament by the time she was a senior.

“I’ve never been a feminist, as such,” Lake says. “But I always wondered why I didn’t get treated like everybody else—especially on the basketball court.”

During those years, Lake was also part of the first American team to win a medal in a major international competition in the Title IX era, the 1973 World University Games. Alongside teammates from onetime women’s basketball powerhouses like Wayland Baptist College and John F. Kennedy College—as well as a young Pat Summitt shortly before she became the University of Tennessee’s head coach—Lake traveled to what was then still the Soviet Union. The U.S. went 5-2; both losses were to the host team by a total of 87 points.

“We had a good team, but the Russians kicked our butts,” Lake recalls. “They were gigantic. But we got the silver medal.”

A mother’s lessons to her daughter

To her everlasting regret, Lake didn’t try out for the U.S. team that won silver in the inaugural Olympic women’s basketball tournament in 1976. She instead returned home after college and began a post-basketball life. But the World University Games medal was a central part of her daughter’s childhood.

It never struck Ralph as unusual that her mom coached her youth teams, even if dads coached most of the other teams. It was the reaction the silver medal on display elicited from visiting friends—“Your mom did what?!”—that clued her in that her family history was different than most.

Most moms didn’t have international medals. Or play in your pickup games.

“I started understanding, yeah, she’s different,” Ralph says. “Most people’s moms aren’t playing basketball with them on Saturday afternoons. I liked that.”

Her memories are full of the familiar squeak of sneakers and bouncing balls reverberating in an empty gym at the community college where Lake taught mathematics. Though Ralph usually had to cajole friends to give up their weekend afternoons to ensure a quorum for pickup games, she could always count on her mom to play. Ralph’s perfectionism, she remembers, meant that it was better for all involved if she and Lake didn’t play on the same team.

“I don’t think I was the easiest kid to raise,” Ralph says. “All I wanted to do was play basketball. I still did what I was supposed to do, but it wasn’t always easy for her to get me to do some of the things that I didn’t want to do. On the court was easy, for the most part. Off the court, I think, was probably tougher for her. I was just really headstrong. And God has paid me back 100,000 percent with my extremely headstrong 3-year-old daughter.”

From the pickup games and pointers to the 200-mile weekend trips so Ralph could play with a nationally competitive AAU team, Lake did all she could to facilitate Ralph’s basketball development. She even called Summitt to ask her old teammate for an honest assessment of her daughter’s potential. Lake hoped Ralph would play at Tennessee, or at the very least follow in her footsteps at North Carolina. That Ralph ended up playing for Tennessee’s biggest rival, the University of Connecticut, is evidence that Lake didn’t try to choose her daughter’s path. Ralph chose Connecticut, won over by legendary coach Geno Auriemma’s bluntness and his promise to make her earn every minute she played.

In her day, Lake had four coaches in four years at North Carolina—the coaching task had generally fallen to whoever in the athletic department couldn’t avoid it. Knowing that, Ralph couldn’t resist the opportunity to play for someone who made women’s basketball feel like it mattered more than anything.

Ralph arrived at Connecticut a year before Title IX’s 25th anniversary, when women’s sports were at an inflection point. A year earlier, American women had starred in and dominated the 1996 Olympics. Athletes like Mia Hamm and Lisa Leslie were no longer niche stars.

The Huskies were undefeated national champions in 1995, and they had emerged as a cultural institution in their state. As home games sold out and nearly every game was on television, Connecticut became a worthy foil for Tennessee in a rivalry that lifted the sport’s national profile to new heights.

Ralph persevered through one of the most star-crossed college athletic careers on record—enduring five ACL tears while still winning a national championship and the Honda Award as the nation’s best player in 2000. Her determination captured hearts, and she became a household name throughout women’s basketball and across Connecticut.

“I don’t know that either one of us was prepared for what we experienced at UConn,” Ralph says. “We had never experienced anything like that before. I know for my mom it was really cool. She was North Carolina’s first All-American, and if women’s basketball had the attention that it had when I played, she would have had that kind of attention in the community. She had her own, but it wasn’t the same. I know it was cool for her to experience that with me.”

The world they made

Now, a year before the 50th anniversary of Title IX, Ralph is taking her next step at Vanderbilt. In her first head coaching role (she served as an assistant at Pittsburgh and Connecticut), she has the opportunity to shape the future of one of the sport’s historically significant programs.

She doesn’t have to worry about having enough basketballs at practice or how the team will get to road games. The unprecedented $300 million Vandy United campaign, which aims to provide all of Vanderbilt’s student-athletes with the best experience in college athletics, is netting her program its own practice court and refurbished locker room.

And when the university athletic director—former basketball student-athlete Candice Lee—invites her for a meeting, it isn’t likely to be because she has a problem with Ralph advocating for equity.

That is the world created over the past 50 years.

“Shea is a living example of the transformation of women’s sports in this country,” says Lee, now vice chancellor for athletics and university affairs and athletic director. “Her mom was a tremendous basketball player in the early days of Title IX, competing at the collegiate and international levels without a scholarship and before women’s sports were even a part of the NCAA.

“Then by the time Shea comes along, she’s one of the most highly recruited players in the country and becomes a part of a legendary NCAA program at UConn as a player and assistant coach. To have Shea now leading our program at Vanderbilt, as we approach the 50th anniversary of Title IX and celebrate the legacy of women’s sports on campus, is a special opportunity for our university and for a new generation of basketball players.”

Ralph is cautious about delivering too many history lessons to her student-athletes, especially if she is the main character. She remembers rolling her eyes when her mom launched into stories about the glory days—and also usually offering a teenager’s typically sarcastic coda about her mom probably also walking uphill both ways in the snow to the gym.

It’s among the reasons she was pleased to add former Vanderbilt basketball student-athletes Ashley Earley and Christina Foggie to her staff as assistant coach and chief of staff, respectively. Their back-in-the-day stories may better resonate with current Commodores, drawing on shared experiences at Vanderbilt and first-hand knowledge of the names and faces from the school’s history who still regularly visit Memorial Gymnasium.

And yet Ralph’s history will shape Vanderbilt whether or not she shares her tales of yesteryear. She is shaped by it, and by her mother’s history. While Lake and others like her didn’t endure inequalities just so Ralph could win a national championship or be selected in the WNBA draft, both did come to pass. Those earlier generations pushed to play because they wanted the same access that men traditionally had to all aspects of sports—the competition and camaraderie, the challenge and opportunity to grow as people. That’s the heritage a mother passed down to a daughter, and it’s what Ralph feels compelled to pass on to her student-athletes.

“I’ve experienced so much as a basketball player for as long as I can remember, and that includes my mom and the stories that she shared,” Ralph says. “Now I can give them a well-rounded holistic approach that I hope will help them grow as human beings.

“I’ve experienced so much as a basketball player for as long as I can remember, and that includes my mom and the stories that she shared,” Ralph says. “Now I can give them a well-rounded holistic approach that I hope will help them grow as human beings.

“That’s my job. Basketball is what we do here, but I think a lot of my growth as a human being contributed to my success on the basketball court. It was when I became a better person that I became a better teammate. When I learned how to care about others—leading as caring, serving and inspiring—not just about going out there and scoring a bunch of points.”

Even if they don’t know all the names and feats of the women who came before them, current and future Commodores will directly benefit from the efforts of those like Lake, who began the journey. In Ralph, Vanderbilt hired someone who can lead the program into the future while respecting and honoring where the game came from.

Looking out at the audience in April, Vanderbilt’s new coach was grateful to share the moment with the mother who made it possible.

— Graham Hays covers Vanderbilt for VUCommodores.com.

Follow him @GrahamHays.