Oct. 29, 2008

![]() Toomay Interview Part 1 (pdf) | Commodore History Corner Archive

Toomay Interview Part 1 (pdf) | Commodore History Corner Archive

>>> Read More Features, Columns and Blogs on VUcommodores.com

|

|

This interview with former Vanderbilt football and NFL player Pat Toomay is exclusive to Commodore History Corner and VUCommodores.com. It will presented in two parts to cover his interesting and fascinating career.

Pat Toomay has consumed quite a life.

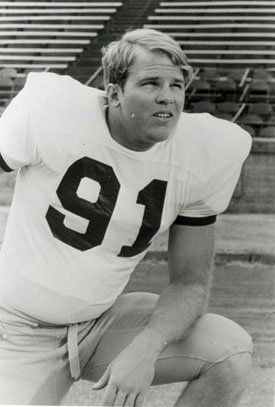

The former Vanderbilt defensive end (1967-69) played in the NFL for legendary coaches, Hall of Fame teammates, authored two successful books and worked with an Oscar-winning movie director. Toomay was born in California, but played his high school football in Alexandria, Va.

“My dad was a career Air Force officer and so we lived all over the place,” Toomay said recently. “We moved about every three years. I was born in California, lived in Hawaii for a while then on the East coast in upstate New York. As I got older my dad had to go to Washington D.C. a lot so we moved to D.C.

“While I was in high school, a neighbor of ours in New York had played for Red Sanders at Vanderbilt. He was J.P. Moore. The Moore’s had kids the same age us so we would play pickup games. That’s how I first heard about Vanderbilt. His son, Jerry, went to Arkansas and ended up playing for the Chicago Bears for a while. They got transferred to Washington too.”

Toomay was heavily recruited as a quarterback and could have played for just about any college in the country. At this time the Commodores’ head coach was Jack Green. Green was going head-to-head in recruiting with such college powers as UCLA, Purdue, Penn State, Stanford and dozens of others.

Toomay was a three-sport athlete in high school playing the pivot in basketball, pitching on the baseball team and quarterbacking in football. But it was a high school teammate that eventually led Toomay to Nashville.

“Bob Cope was the recruiter for Vanderbilt,” Toomay said. “I am six-foot-five and Bob was five-foot-six. He was the most persistent and a charming coach. He wouldn’t take no for an answer. He kept coming and coming. I had a receiver and high school classmate named Curt Chesley. Curt was a magnificent athlete in all sports. We swept everything in Northern Virginia in all sports our senior year as far as accolades, but no one was looking at him.

“I said to Cope and Green if you guys will look at Curt and tell me what you think of him that will help me make my decision. Green saw Curt’s bicep and said come on down for a visit. Curt went and they signed him. I signed and Curt went on to be a leading receiver in the SEC. His two brothers followed him there as well. I would play as a free safety, standup linebacker and defensive end.

“I had never been that far in the South before and that was appealing to me. I liked the idea it was a small private school with a high academics standard reputation. Vanderbilt was recruiting me as a quarterback, but I couldn’t throw the out pattern. I started playing baseball and throwing junk at age nine. By the time I got to Vanderbilt my arm was shot. They moved me to free safety and then to the line.”

This was in 1966 when Toomay was on the Vanderbilt freshmen football team in an era where freshmen were ineligible for the varsity. Green was in his fourth season leading the Commodores’ football team. This would also be his last season coaching at Vanderbilt. In his four years Green recorded a 7-29-4 mark.

“Black” Jack Green was my first coach at Vanderbilt who was an Army All-American guard,” said Toomay. “He chewed tobacco and was a tough guy. They brought in Bill Pace during my sophomore year. As a man, Pace was a different style coach. He was more cerebral and shaped the team to the personnel we had. Dudley Field was a great field and you could feel the tradition there.

“When Alabama came in there that year (1967) it was electric. Vanderbilt was focused on building a team. For us younger guys just being on the field with Alabama, Bear Bryant and Kenny Stabler was an experience. I played across from Danny Ford who was a tackle and later Clemson coach. Later we beat Alabama there (1969) that was the highlight of my college career. Bryant said privately that losing to Vanderbilt was the lowest point in Alabama history. The entire campus and Nashville went crazy for weeks after that game.”

Another Vanderbilt coach had an interest in Toomay. Head basketball coach Roy Skinner could have included Toomay on the Commodore basketball roster if things had been different.

“I went to Vanderbilt on a double scholarship.” Toomay said. “My deal was that I could play football and basketball and then choose the sport to go fulltime. I had the privilege of playing with and getting to know Perry Wallace. Vanderbilt was a pioneer in integrating the SEC. Perry was a tremendous person and playing on the basketball side was a tremendous experience for me.

“I played basketball my freshman year. I was a six-foot-five inch pivot man and played inside. I was a garage guy. I could play facing the basket. They had guys that were six-foot-five, six-foot-seven who could play guard so physically that I was not a fit. Had I played basketball I would have been a Gene Lockyear kind of guy. A muscle guy, rebounder. On the football side guys with size were in higher demand and appreciated more. So, I decided to focus on football.”

Toomay would play in the 1969 Blue-Gray Classic. The College All-Star game for seniors began in 1939 and was discontinued after 2003. The game was traditionally played in Montgomery, Ala., on Christmas Day. It was a showcase for NFL scouts who were ranking players for their college draft in the spring.

“It was difficult for the horror of it; it was no fun,” said Toomay. “You are on your Christmas vacation in a strange hotel with a bunch of people you don’t know. Then there was pressure because I weighed about 220 pounds throughout college. Then the pros came around and their ideas are what you can do for them later. Their influence comes to bear on how the game is played and who plays where. They wanted to see me as a standup linebacker.

“At Vanderbilt I would play down some of the time, but mostly I was a standup end in the defense we played mostly with run responsibilities. I had to play a pro linebacker in the game. It was tricky for me in that regard to learn that new position. I was an “in betweener” physically. Dallas as sort of a project drafted me. I gained about 25 pounds in the winter after my senior season to make that transition.”

The Cowboys drafted Toomay in the sixth round as the 153rd player selected overall. Also taken in that 1970 draft by Dallas was Toomay’s Commodore teammate, offensive tackle Bob Asher. Asher was the Cowboys second pick and 27th overall. Duane Thomas was the Cowboys top selection that year. The year 1970 was also the merger of the National Football League and the American Football League. The NFL now had a National Football Conference and an American Football Conference.

Bucko Kilroy was the primary scout from Dallas that was impressed with the future of Toomay as a professional football player. Toomay thought he would be drafted but, wasn’t sure where he’d end up.

Toomay was also about to enter a big mess in the NFL due to a lockout by the owners and a strike by the players.

“The strike did not affect the rookies, but it affected the veteran players,” said Toomay. “It was an opportunity for me because they brought in a lot of people as they always did. We had to start into the exhibition season. They formed a team out of who they brought in that year. They had a lot of time to look at us. That was good for me.

“We were not crossing a picket line since we had not made the team and joined the union. We were just a bunch of guys. At that time they played six exhibition games. Usually the rookies got very little attention except for the top draft picks and a few others. Everybody else is just fodder. Without any veterans they had to form a team and look very closely at the personnel and people could rise.”

Toomay did make the Dallas squad and was playing with defensive teammates as Jethro Pugh, Bob Lilly, Lee Roy Jordan, Chuck Howley, Mel Renfro and Cliff Harris. In the previous year the Cowboys were 11-2-1 and winners of the Capitol Division, but lost to Cleveland in the Eastern Championship game.

The Cowboys became an NFL franchise in 1960, but never won the NFL championship game. They played two historic games with the Green Bay Packers that resulted in losses. Losses came to the Packers in 1966 and the Ice Bowl in 1967. The leader of this collection of players was Tom Landry.

“I was fascinated,” said Toomay. “Most of these guys were from bigger programs. Lee Roy Jordan and Chuck Howley I knew about. Lilly and Pugh had just come off those great games with the Packers. And of course, everybody knew of Tom Landry. A lot of the coaches at that time had a military background and I had grown up in that environment. So, I got that piece of it. I could see that Landry had an elegant system that was difficult to learn. He needed guys that could mentally understand the system and see the virtue of learning it, which probably took three years to master.”

In his rookie season, Toomay played in all 14 regular season games and playoffs with an occasional start at defensive end. Landry had been the Cowboys head coach from the team’s inception in 1960. Toomay had great respect for Landry and considered his coach a mentor.

“I found that there were constraints for me being around Landry,” said Toomay. “Dallas was very image conscious. When the ownership and management turned on the TV, they wanted to see a particular kind of guy saying particular things. I would push that envelope. That got to be a frustration. In 1973, I started and led the team in sacks then in 1974 they drafted Ed Jones No. 1 in the entire draft who was a defensive end. The next season Larry Cole and I became run specialists, but I was a pass rusher. Having been a running quarterback in high school I could get free a lot and I didn’t see that I was allowed to use my potential.

“After five years I played out my option. I would have been on the bench. A No. 1 pick is going to be on the field regardless. I knew that I could play for a lot of teams all the time. Dallas didn’t pay well. They were in the bottom third in the league as far as salaries. Their justification was if you come with this great organization you will go to the playoffs and you will make it up that way. I didn’t like that either.”

In 1970, the Cowboys would win the Eastern Division with a 10-4 record behind quarterback Craig Morton. They went on to defeat Detroit (5-0) to advance into the NFC championship game. They defeated a John Brodie-led San Francisco team (17-0) to earn a match against the AFC champion Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl V.

In that Super Bowl played in Miami’s Orange Bowl, the Colts kicker Jim O’ Brien booted a 32-yard field with five seconds on the clock to break a 13-13 deadlock for a 16-13 victory. The offense for both sides was so ineffective that Howley was named the game’s MVP award for his two interceptions and fumble recovery.

“I got to play more that year in a number of key games towards the end of the season,” Toomay said. “I had to play out of position and into Coles’ position. The Super Bowl then is not what it is now. But, it was still an amazing thing. Of course, the Colts won that game. The Cowboys had lost to Green Bay and they lost a lot of big games.

“They were known as not winning the big one. Lilly after that game threw his helmet a record high up in the air. I was not on the field when the Colts kicked the winning field goal. I was a rookie and in that game I was covering kicks. The following year things started to come together.”

The Cowboys did put it all together that next season. They won the East with an 11-3 record and won their division playoff game 20-12 at Minnesota on Christmas Day. This propelled the Cowboys into the NFC championship once again against the 49ers. Dallas won again at home, 14-3.

The opponent for Super Bowl VI in New Orleans was the Miami Dolphins led by quarterback Bob Griese and head coach Don Shula. The Cowboys were now being led on the field by quarterback Roger Staubach. Staubach was the game’s MVP as the Cowboys dominated the contest, 24-3.

“I was playing behind George Andrie who was an old vet and I beginning to play a lot,” Toomay said. “It was an amazing experience to win a Super Bowl. It was a huge high point for me as I got married after the season. You go to two consecutive Super Bowl games in your first two years in the league; you think you are living a charmed existence.

“Staubach was the quarterback at this time. He had come out of the service in 1969. He was four years older than us that came in 1970 and he was learning as we were. A guy like Roger with a Heisman Trophy background was a great leader. It was a thrill to be around people with that great of a quality.

“As he started to become one of the regulars, Roger wanted to be one of the boys. Walt Garrison persuaded him to try snuff. Roger did and he was sick for about six days. He appreciated practical jokes and was a ferocious competitor.

|

|

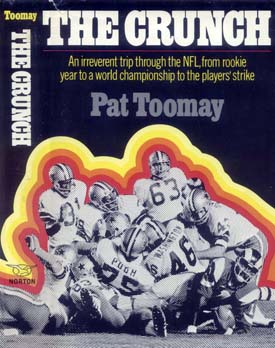

When Toomay played out his option ending his five-year stay with the Cowboys, he gained attention as a writer. His book, “The Crunch” was published and not well received by all connected to the National Football League.

The jacket of his book, published in 1975, asks: “Who is Pat Toomay? He is an intelligent, funny man who just happens to earn a living as one of the best defensive ends in pro football. And what he has to say about the game, the front office, and his fellow professionals is stuff you won’t hear or see on the “Monday Night Game of the Week.” He describes his frustrations, the colorful personalities, the red tape and insane regulations generated by the front office–and treats them all with the freewheeling humor they deserve.”

So, why would Toomay write such a book that was considered controversial and maybe possibly harmful to his teammates?

“I didn’t deliberately set out to write a book to have published,” said Toomay. “What I found was an image reality contradiction. The game is presented in a certain way. I grew up with NFL Films and John Facenda (the narrator with that strong memorable voice) and my father’s fascination with the game. When you get there you find that it is more complicated than that. I just started keeping some notes and I kept a journal during training camp. Some silly things would happen and some aspects bothered me so I jotted them down. I sent a copy of what I had written to my dad for Christmas just so he could see what I was going through.

“There were some things that happened in the NFL that doesn’t show up in films or printed in the newspaper. One of the things that got me was the physical battering. We were a much of kids there and when the veterans came in the physical battering began. The joints and the number of knee surgeries and the shots put a new twist of things on me that this activity is more complex than I thought. You didn’t see it college that much because people weren’t around for 10 years. There were horribly misshaped knees from five or six surgeries. I had surgery at Vanderbilt my freshman year; it was a knee injury. I was very lucky. I realized how much luck there was getting to that level and staying there.”

“It was irreverent is how they described my book. I suppose it was. I was talking about the things that underline the presentation. I was basically presenting people as human. The people in charge of media and image were not particularly thrilled. They weren’t thrilled with me talking about everybody being human. The marketing aspect is these are super human guys and can do anything. So, I just took down what I was seeing and experiencing.

“John Bibb (Tennessean sports writer) was a very good friend of mine. I sent a copy of these pages to him just for his own entertainment. He handed off the pages to John Seigenthaler (Tennessean publisher) who wrote a note back asking if there were anymore because he knew a publisher who might be interested in publishing those types of observations. I just kept making notes. Seigenthaler was a great supporter of me the rest of the way.”

The book was popular and a best seller. It give the inside impressions of life in the NFL unknown to the average fan. Some teammates were not happy with their portrayal in the book.

“I had left Dallas when it was published,” said Toomay. “I played out my option and the book came out when I was in Buffalo, which was in a different conference. Some guys were annoyed. It wasn’t a “Ball Four” (written by former baseball player Jim Bouton) kind of thing. I wasn’t buying into it totally. I wasn’t a total convert to the system and what they were doing and that was a reflection of the times. I thought the Vietnam War was a bad idea so I was more on the protesting side of things than on a conservative side. It was a controversial time.

“There is a direct relationship between the military and football. It is sort of a mirroring of war. It draws a lot of military people as coaches. Landry was a bomber pilot in World War II. It carries over. If you look into (Vince) Lombardi’s history, he was at Army where he would brief General (Douglas) MacArthur on game strategy. The training is the same though you don’t get killed in football. You get maimed. The NFL was criticized during that period being an arm of the military industrial sensibility. Look at the language–blitz–a lot of the language carries through.”

Next week read part two about Toomay playing football at Buffalo with O.J. Simpson, Tampa Bay and the 0-14 season, playing for Oakland’s John Madden and his involvement in Oliver Stone’s film “Any Given Sunday.”

If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via e-mail WLTraughber@aol.com.