Lily Williams Goes for Gold

by Graham HaysLily Williams thought she was done with sports when she graduated. Five years later, she's racing in the Olympics.

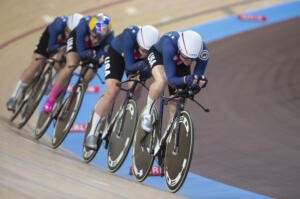

Lily Williams, BA’16, an elite track cyclist representing Team USA, will soon become the first female Vanderbilt graduate to compete in the Olympics. A member of the 2020 women’s team pursuit squad that won the UCI Track Cycling world championship, Williams has a good chance to become the second Commodore to ever win a gold medal.

Given the route the former middle-distance runner took from Nashville to the Izu Velodrome outside Tokyo, she is also among the unlikeliest Olympians in the American delegation.

It was a job application that put Williams on the path to Tokyo. The daughter of an Olympic speed skater, she began her own Olympic journey after walking away from sports. Shortly after graduating from Vanderbilt, and with little expertise other than riding around campus on a bike she bought in Edgehill, she applied for part-time work in a bike store. She got the job and, in the process, also found a passion.

Five years later, Williams is racing for gold.

“It is unusual,” said Gary Sutton, a two-time Olympian who now heads the women’s endurance track program for USA Cycling. “There have been some great champions that have crossed over from rowing and athletics and stepped up—most of them probably not as quick as Lily has, to be honest with you. There’s not too many. It’s just amazing how Lily has progressed.”

REKINDLING THE COMPETITIVE FIRE

In 2016, after earning her degree in biology and English from Vanderbilt, few would have been more surprised than Williams about what awaited her. A student-athlete on the cross country and track and field teams, she ran her final collegiate mile that spring in the SEC Championships in Tuscaloosa, Alabama—the same weekend as Commencement in Nashville. In her mind, those laps marked the end of her competitive career.

Accepted to a graduate program at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, she packed up her things—including the bike—and moved to the Chicago area.

“I was so ready to be done with sports,” Williams recalled. “I was ready to just not be a competitor. With sport, a lot of it is failure. You have good races, but a lot of times you have bad races. And I was just really burned out.”

While not an outright phenom, she arrived at Vanderbilt as a talented prospect. Not only did she win high school track titles in Florida in the 800, 1,600 and 3,200 meters, she won all three in the span of an afternoon. As a prep runner, she had some of the fastest mile times in the nation for her age group and was a three-time runner-up for the state title in cross country. Though she won some races and enjoyed the camaraderie of the Vanderbilt team, her passion for running waned.

Longtime cross country and track coach Steve Keith, BA’81, saw Williams as someone who was pulled in new directions, with a creative and analytical mind exploring avenues outside of athletics. He saw the burnout. But he didn’t see someone who was done with sports.

“I’m sorry, that doesn’t happen,” Keith chuckled. “You may take a little sabbatical, but that is ingrained in her nature, that athletic part of her. She didn’t realize it, but she was going to get back into it one way or the other.”

Other is an understatement. To help offset graduate school expenses, Williams emailed several bike shops in her Chicago neighborhood in hopes of part-time work. Turin Bicycle responded within an hour, eager for someone to help assemble bikes and work the floor.

Bikes weren’t foreign to Williams. Her mother, Sarah Williams (then Sarah Docter), had competed for a few years in cycling road races in the United States and Europe—in addition to competing for the United States in speed skating in the 1980 Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. While that was well before Lily’s arrival, she and her sister, Cecelia, grew up at least aware of cycling culture.

At Vanderbilt, Williams rode to class and to summer internships across Nashville. She also rode to unwind on the trails in Percy Warner Park. Cycling was a means of transportation more than anything else, and it remained that way until co-workers in the Chicago shop convinced her to try cyclocross—a discipline in which competitors ride, and sometimes carry, bikes around largely unpaved courses. Soon she was hooked.

From cyclocross, she began competing in road races with Northwestern’s club cycling team. She won a small regional race early in 2017 and hoped to latch on with a team for the Joe Martin Stage Race, a long-running annual event in Arkansas. She didn’t have any takers at first, but when one team lost a rider to injury a few days before the race, she drove to Fayetteville on her own dime and filled in.

“I really probably shouldn’t have been there,” Williams said. “It’s one of the few truly professional-level races in the United States, and you should probably have some experience before you go do that race.”

She nevertheless won a stage racing against the professionals. That helped her eventually earn a contract with the Rally Cycling team to continue competing in road events. More strong showings, especially in sprints, caught the eye of Kristin Armstrong. Armstrong is a three-time Olympic gold medalist in cycling (and no relation to Lance Armstrong), which meant that Sutton listened when she suggested that he keep an eye on Williams.

In fall 2018, USA Cycling invited Williams to train on the track in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

OLYMPIC FAVORITE

Track cycling takes place on banked ovals—a 250-meter oval with 45-degree banking in the case of the Izu Velodrome. It is divided into a variety of sprint and endurance disciplines, although even endurance disciplines like the 4-kilometer team pursuit are considerably shorter than road racing distances. Williams knew that team pursuit, at the world-class level, was around a four-minute event, a similar physiological profile to running the mile in track.

“Physically she was very good,” Sutton recalled. “She was very strong. Her technique was very average, but you expect that when someone hasn’t been on the track before. When you said to her ‘Just try and do this,’ she would always nail it the first go. She fully understood what you were asking of her and took it in.”

Little more than a year later, Williams was part of the American entry that beat reigning Olympic champion Great Britain and won the team pursuit in the 2020 UCI Track Cycling World Championship in Berlin. While track cycling has a history of pulling athletes from other sports—notably Great Britain’s Rebecca Romero winning gold in rowing in 2004 and in cycling four years later—Williams went from bike shop employee to world champion in barely 40 months.

“Leading up to that point in my athletic career, I’d had a lot of ups and downs,” Williams said. “It was a really nice affirmation that all the hard work I’d put in had paid off.”

The world title in 2020 established the Americans as Olympic favorites but also came at the end of February, just days before the pandemic shut down much of the sports world and postponed the Tokyo Games. While Williams would have been part of the team without a postponement, Sutton called the additional year of training a “game-changer” for her development.

In team pursuit, four-person teams ride in head-to-head competition against an opposing team that travels in the same direction but begins the race on the opposite side of the track. A team wins by either catching the other team or, if that doesn’t happen, completing the distance in the fastest time. Each team’s cyclists ride at speeds approaching 40 miles per hour, as close as possible to each other to improve aerodynamics (like bumper-to-bumper stock cars). Riders take turns leading the pack, and communication during the race is essential. While still the newest member of the team, Williams is increasingly an equal partner.

And all of it began with that job application that she thought was part of putting athletics behind her after her time competing for the Commodores.

“It’s been really nice as I move into my adult life to be able to achieve some of those things that during my time at Vanderbilt I didn’t know if I would be able to achieve,” Williams said. “The rigor of Vanderbilt really prepared me for the world in a lot of different ways.”

She is now a professional athlete; Rally Cycling allowed her to put road racing on hold to train on the track during the buildup to the Olympics. She hopes cycling may one day allow her to be a full-time professional, though that may mean returning to road racing and a life abroad for the largely Europe-based professional circuit. For now, in addition to the daily training routine, she is director of communications for Bike Index, a nonprofit organization that lets users register their bikes and crowdsource recovery efforts if a bike is lost or stolen.

Williams left Nashville certain that she was done with sports and unsure whether she would find a community as welcoming and supportive as Vanderbilt. Cycling proved her wrong on both counts. She isn’t living the future she envisioned when she arrived at Vanderbilt from Tallahassee, Florida, or even when she departed Nashville four years later. But if Vanderbilt didn’t prepare her for team pursuit, it prepared her for life. From the biology lab to the providentially named Red Bicycle Coffee, where she would bike for crepes, Vanderbilt prepared her to follow her passions wherever they led.

“It was the first time that I’d really interacted with literally anybody who was different than me,” Williams said. “It was such an amazing place to learn about the world and meet all sorts of people and prepare me for reality after college. I miss my time there a lot.”

She hopes to return soon, but she is a little busy at the moment.

Williams in the Olympics

Qualifying for team pursuit will take place Monday, Aug. 2, beginning at 1:30 a.m. CT. Medals will be decided over two subsequent rounds on Tuesday, Aug. 3, beginning at 1:30 a.m. CT.

— Graham Hays covers Vanderbilt for VUCommodores.com.

Follow him @GrahamHays.