Nov. 9, 2011

Editor’s Note: Nashville sports historian Bill Traughber has recently written another book, Vanderbilt Football: Tales of Commodore Gridiron History. The 160-page paperback book can be ordered on historypress.net for $19.99.

Commodore History Corner Archive

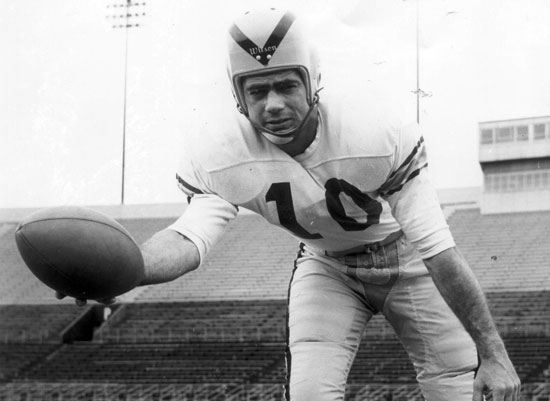

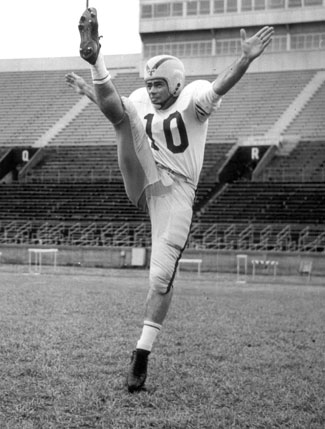

When former Vanderbilt football player and NFL official Don Orr was 14 years old, he faced a challenge that could have affected his life forever. While his schoolmates and friends were playing ball, Orr was diagnosed with polio.

“Some doctors said I would never walk or run again,” Orr said recently. “I was one of the lucky ones. There were people with polio in iron lungs, casts and everything. I stayed in the hospital for three months and after therapy had to learn to run all over again. I ran with a limp, but it eventually left me.”

Orr, who played for the Commodores from 1954-56, had been active in sports and believed his illness was contracted at a Boys Scouts’ camp. He was born and raised in Miami, Florida playing high school football as a junior and senior at Andrew Jackson High School. Orr played quarterback and defensive back in high school and his best memory from those prep days was beating rival Miami Senior High for the first time in 27 years.

Orr had other options for college than Nashville and Vanderbilt.

“I had an academic scholarship to Dartmouth and Northwestern,” Orr said. “I was also offered a football scholarship to Miami and Florida. Vanderbilt use to play the University of Miami and whooped up on them in those days. I thought that they were a big Southeastern Conference team. I didn’t want to go to Miami because I wanted to leave home. My dad was a big Miami fan and he said, `well if you aren’t going to play for Miami, you aren’t going to play for Florida.’ That didn’t leave me too many choices so I chose Vanderbilt.

“I came in under Bill Edwards and was recruited by his assistant Buford `Baby’ Ray who I thought was the biggest human being I’d ever seen. Edwards was like a pro coach. They brought in about 75 or 80 of us as freshmen. They just beat the living hell out of us. I guess some of the better ball players left. I think in our graduating class we only had about 24 players left out of that 80.”

Orr suffered a setback as a freshman in an era that first-year players were eligible for the varsity. During a practice, he was knocked unconscious while being kneed in the head causing a severe concussion and placed in the hospital with double vision. Art Guepe replaced Edwards before Orr’s sophomore season in 1954.

Orr missed a lot of his sophomore season with a foot injury. By his junior year, Orr was starting at quarterback alternating with Jim Looney. He also doubled as a safety on defense. In 1954, Vanderbilt ended its season at 2-7 (1-5 SEC) and a 26-0 victory over Tennessee in Nashville. Orr said that his biggest thrill from that UT game was punting the football over Johnny Majors head for about 60 yards. The next year as a junior, Orr and Vanderbilt would make Commodore football history with its first-ever bowl appearance.

“I started the entire year at quarterback,” said Orr. “We beat Alabama (21-6) and No. 17 Kentucky (34-0). The Kentucky game was the biggest game. They were favored over us and we really beat them. Blanton Collier was their coach. One of our assistant coaches picked up a tip on the right halfback Dick Moloney of Kentucky.

“He staggered his feet in the direction that he was going so we just keyed on him all day. We called `red’ or `blue’ whatever the signals were in which the direction the play was going. We just stuffed them all day long. Then at the end of the game we were hollering, `don’t hurt Moloney.’ We wanted him to stay in the game. We intercepted three or four passes and just killed them. After the game was over we told them about being tipped off.”

Vanderbilt finished that historic year 8-3 (4-3 SEC) with an invitation to the Gator Bowl against Auburn. But Orr and his teammates were not pleased with the Gator Bowl invitation.

“We were disappointed in getting the Gator Bowl,” Orr said. “If we had beaten Tennessee, which we should have, we would have played in the Sugar Bowl. When I got hurt in the Tennessee game, the substitute they put in for me, watched a bomb go right over his head for the winning touchdown. They beat us 20-14 and that knocked us out of the Sugar Bowl. We didn’t think we’d get anything, but the Gator Bowl offered us the game.”

In the Tennessee game Orr suffered a dislocated elbow in his passing arm, which made it doubtful for him to appear in New Year’s Eve contest against the No. 8 Tigers in Jacksonville.

“In the Vols game, I was playing safety and I went over the receiver’s shoulder to knock down a pass,” said Orr. “I mistimed it and went over the top of him and put by arm down to brace myself and dislocated my elbow. I thought I would be able to play in the bowl game, but the coaches didn’t think so.

“I didn’t practice much. I could throw the ball fairly decently. They taped my elbow so I couldn’t extend it. I thought I could play. Before the game, Coach (Art) Guepe said if we started on defense he was going to start Tommy Harkins. I said, `Coach, I don’t think that will get the job done.’ They decided to start me. I did play both ways.”

Vanderbilt beat their fellow conference member 25-13 to finish that remarkable season at 8-3. Orr was named the game’s MVP after scoring two touchdowns on the ground and passing for a third.

Vanderbilt beat their fellow conference member 25-13 to finish that remarkable season at 8-3. Orr was named the game’s MVP after scoring two touchdowns on the ground and passing for a third.

“There was one funny moment I remember from that game,” Orr said. “We lined up for an extra point with Earl Jalufka our kicker. To get his spacing right, Earl would do a push up where the ball was spotted. He was doing a pushup when one of the Auburn guys said, `what the hell you guys doing, calisthenics?’ Our captain Jim Cunningham was the center and he raised his head up and said, `well, we’ve got to do something for exercise.’ Everybody broke up laughing. And then Earl missed the extra point.”

As a senior, Orr was a team captain along with Art Demmas who would also become a longtime NFL official. The Commodores were 5-5 (2-5 SEC) that year. Early wins would put Vanderbilt ranked as high as No. 13 including a 32-7 victory over Alabama. However, the Commodores lost five of their final seven games.

Orr was invited to play in the annual North/South All-Star game in Atlanta. The South won the game 33-7 with Orr playing quarterback in the first half. Sonny Jurgensen of Duke relieved Orr in the second half. NFL Hall of Famer Len Dawson was the starting quarterback for the North squad. After graduating from Vanderbilt with a degree in electrical engineering, Orr had an opportunity to continue his football career.

“I got drafted by the Bears in the 26th round, but never talked to them,” said Orr. “I had two or three concussions and didn’t think it was too smart to try and play professional football. I was in ROTC in college and received a commission as an officer. In January 1957, I reported to the army at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas.

“I was there for six months. I had two years, but the Korean War was over and they had so many second lieutenants that they didn’t know what to do with them. They took the class in front of mine, and the class behind me and put us back to six months. When I left the army I went into business, but I spent six years in the reserves and had to go to Fort Sill (Oklahoma) every summer.

“I went to work for Nashville Bridge Company and stayed there for nine months then I was offered a job at the Nashville Machine Company. They were looking for a young engineer. I went to work for them in 1958. Then in about 1968 the gentleman that was president purchased the controlling interest in the company with me. Then he retired in 1995 and I retired in 2006.”

Orr continued his interest in football by becoming an official. Having contacts and some luck, Orr would gradually move into the world of professional football.

“When I came out of the army and back to Nashville, Dave Scobey (former Vanderbilt athlete and SEC official) suggested that Charley Horton, Art Demmas and myself join the high school officiating bunch. After working three years in the high school level, Art Guepe came to Art Demmas and myself and asked if we were interested in officiating in the Southeastern Conference. He told us to put our application in that year because he was the chairman of the selection committee.

“So we did and we got in. Art and I were two of the four that they selected. I was in the league for about 10 years. In my 10th year, I was working the UCLA/Tennessee game in Knoxville as the referee. There was a pro scout there to watch somebody else who had applied to the NFL. Before the game the scout asked me if I minded that he sit in on our pregame official’s meeting. I told him he was welcomed. On Sunday he called me and asked, `are you interested in getting into the NFL?’ I told him you always want to get to the top of your profession.

“He said he’d send me an application. The guy’s name was Charlie Berry. He was an old baseball umpire that the league had hired to be a scout. He told me not to send it to the league office but to him, which I did. The next thing I knew, Dave Scobey then the vice-Mayor of Nashville, called and asked what was going on that the FBI had asked him some questions about me. They took four that year and I was one of the four. That was in 1970 when I began officiating NFL games.”

Orr said that as a college official his crew is sent a schedule for the entire season and they were required to be in the location the game is played the night before the game. In the NFL, the crews were given their assignment two weeks before a game and were required to be in the NFL city by noon the day before the game.

“In the NFL they had a routine where they send all the films of the games you worked the previous week that has been critiqued play-by-play,” said Orr. “You and the entire crew have to sit through that film, which takes about five hours to review with an NFL officials’ supervisor. If you agree with the critique, you say so, and if you don’t agree then you tell them you don’t agree and explain why we did such-and-such. You very seldom win those arguments.”

Do the football officials at any level know all the rules from the rulebook?

“I will say some of us do, and some of us don’t,” Orr said. “Sometimes when you see us huddling up, we are discussing the correct rule. A lot of it depends on when the foul occurred. Whether the ball was loose. Whether it was in possession. All that changes the enforcement spot. So a lot of time those conferences are to determine the position of the ball when the foul occurred. Between all of us, we will get it right.”

In the NFL there are seven officials on the field with different titles and responsibilities. They are the referee, who is in charge of the game, the umpire, head linesman, side judge, back judge, field judge and line judge.

“I was a referee in college,” said Orr. “When I first came into the NFL, they had a rule that nobody started out as a referee. They put me on the line of scrimmage as a line judge. Most new guys came in as line judges. Then they expanded it to seven officials and I moved downfield as a side judge.

“One time the field judge in our crew got run over and couldn’t work and we had to adjust positions. I had played safety at Vanderbilt and I said I’d move back there and take his place. I enjoyed it so well, and they must have thought I’d done a decent job that the next year they asked me if I wanted to be a field judge, which I said yes. I never made it to referee.

Orr was an official in three Super Bowls. These were Super Bowl XVII (Washington 24 Miami 17); Super Bowl XXIV (San Francisco 55 Denver 10) and Super Bowl XXVIII (Dallas 30 Buffalo 13). Super Bowl officiating assignments would go to the top rated officials.

“They have a grading system of the films in every game you were involved,” Orr said. “They grade you if you make a good call and if you make a bad call. Sometimes they will give you a good grade for not making a call like a good no-call. At the end of the year they add up the grades and the top guys get the Super Bowl. I don’t think you will ever see anybody repeat in Super Bowls. They’ve got some rule or unwritten rule that you can’t get another Super Bowl for three years. Basically the top guys get the Super Bowls and the next eight guys get into the playoffs.”

Orr will never forget January 6, 1980, a cold day in Pittsburgh. The Houston Oilers met the Steelers for the right to advance to the Super Bowl in this 1979 AFC Championship game. The temperature was 22 degrees and falling and piles of shoveled snow surrounded the artificial turf in Three Rivers Stadium.

Late in the third quarter, Pittsburgh was ahead 17-10 and Houston had driven down to the Steelers 6-yard line. Houston quarterback Dan Pastorini tossed the ball into the end zone corner to Mike Renfro. Renfro apparently caught the ball over his left shoulder. Orr was a side judge and ruled “incomplete” since he believed that Renfro did not have possession of the ball before he stepped out of bounds.

The officials huddled to confer. Because of the angle, no other official had a clear view on the play. Since there were no sideline instant replay cameras to consult–Orr’s call stood. The Oilers settled for a field goal and trailed 17-13. Pittsburgh went on to win the game, 27-13.

Is Orr still asked about that controversial call today?

“Not anymore,” laughed Orr. “It was a long time ago. But it comes up now and then amongst my buddies. We had a mechanic back then. If the guy goes out of the end line, which he did, the guy on the side, which was me, watches the football. The field judge, who has the end line, watches his feet. And then you try to communicate by nodding your head or waving it off whether you think it was good or not good. I was watching the ball and it comes over Renfro’s left shoulder and slides down his stomach and then he grabs it on his hip and he is out of the end zone. I looked to the field judge and the field judge is out of position. He is on the other side of the goal post when all this is all happening in the corner. I waved it off.

“Later they sent me eight shots of the play, and you couldn’t tell if he had possession of the ball before his feet went out of bounds. There was a guy who worked for NFL Films that stood behind me and had played for Bum Phillips (Oilers head coach). He agreed that the ball was moving when Renfro went out of bounds. Now I don’t know if he knew anymore than I did. I didn’t get a nod or anything from the field judge. We huddled up afterwards to see who saw what and who didn’t see anything. It was all on me.”

“If they had instant replay back then it would have made my life a lot easier. They would have verified it right then and there or they would have overruled it. As it was I got 500 nasty letters and telephone calls from Houston fans. My wife was in Nashville and she started getting nasty telephone calls before the game was over. I was hung in effigy in the Astrodome. There were two or three nuts that called me at home. Some guy called me about two o’clock in the morning every day. He’d say, `Mr. Orr, you’ve hurt a great number of people. You should be ashamed of yourself’ and he’d hang up before I could say anything. Then the next morning he’d call me again.

Television replays at the time seemed to be inconclusive. The television analysts could not agree themselves. There was some evidence that the ball was moving before Renfro stepped out of bounds. It was ironic that in 1997 the Houston Oilers would move to Nashville–Orr’s home city. Orr said his company purchased eight PSLs for the Oilers/Titans and would attend games.

Orr also threw a future NFL Hall of Famer out of a game.

“I threw out Willie Lanier and caught all kinds of grief about it,” said Orr. “It was because the week before Lanier had been named the `Sportsman of the Year’ in Kansas City. I threw him out because he threw a couple of short punches in a guy’s stomach. The umpire, Tom Hensley, who happened to have played tackle at UT grabbed Lanier by the facemask and walked him to the sidelines. Both of us got chewed out because they said it looked like all Lanier did was push him and not hit him. And nobody should ever grab a player by his facemask.”

Orr retired from the NFL in 1996 after 25 seasons. He retired from his Nashville Machine Company business in 2006. Orr has homes in Nashville, North Carolina and Florida and is enjoying retirement.

“I have known so many friends from my days at Vanderbilt and developed great relationships,” Orr said. “The Gator Bowl thing, we had reunions all the time. Down here in Florida, I regularly play golf with Charley Horton, Bobby Goodall, John Hall and Billy Grover. There must be a half a dozen former Vanderbilt football players down here. We are still very close and follow Vanderbilt football with great interest.”

If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.