Oct. 9, 2007

CHC- Red Sanders (pdf) | CHC Archive

|

|

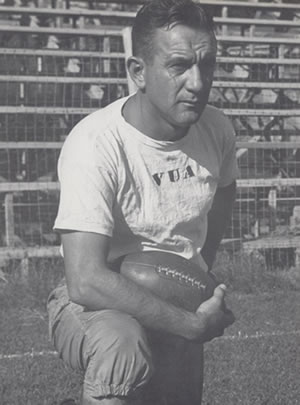

Former Vanderbilt player and head coach Henry Russell “Red” Sanders was born in Asheville, N.C. on March 7, 1905. At the age of two, he moved to Nashville with his family. Sanders received the nickname “Red” by always playing football in a red sweater on the playgrounds of East Nashville.

Before entering Vanderbilt, Sanders attended Eastland grammar school, Duncan School and Nashville’s Central High School. Sanders graduated from Riverside Military Academy (Gainesville, Ga.) in 1923. During his four years at Vanderbilt (1923-26), Sanders lettered in football, basketball and was captain of the baseball team. In football, he was primarily a substitute player and backup to All-American quarterback Bill Spears.

Coach Dan McGugin was said about his player, “Sanders has one of the best football brains I have ever seen.” After graduating from Vanderbilt in 1927, Sanders became backfield coach at Clemson under former Vanderbilt All-American Josh Cody.

In the summer months, Sanders played semi-professional baseball, and then in 1931 he accepted the head-coaching job at Columbia Military Academy in Tennessee. Next was a stop back to his alma mater at Riverside Military Academy in 1934 where he compiled one of the greatest records in Southern prep football winning 55 games, losing four and tying two.

In 1939, Cody, now in his final season as head coach at Florida, hired Sanders back into the college ranks as freshman coach and scout. The following season Sanders was coaching the backfield at Louisiana State University. When Vanderbilt head football coach Ray Morrison decided to leave Vanderbilt for Temple in 1940, a committee tabbed Sanders as the new head coach. One of Sanders’ assistants was Paul “Bear” Bryant.

An article about Sanders from the New York World Telegram in 1954, related Sanders philosophy on football:

“Contrary to general belief, Sanders did not learn his single-wing strategy under McGugin. Dan was a Michigan box man. Sanders says his development as a head coach, and he is confident that he is a good one, stems from contact with three men.

“He learned psychology, particularly the art of handling men, from McGugin. He learned football fundamentals from Cody. His single-wing he learned from Gen. Bob Neyland, great Tennessee mentor–and that’s a story.

“Red never worked under the General. But he scouted Tennessee plenty and the more he saw, the more he was impressed. In the end, he took over the entire Neyland style, later spent many an hour with general Bob going over plays and devising new strategy.”

Sanders had only one losing season at Vanderbilt and that was in his inaugural year in 1940 where he was 3-6-1 (SEC, 1-5-1). He actually was at Vanderbilt in two separate stints. Sanders coached the Commodores in 1940-42 and 1946-48. In between, he was serving in the Navy as a lieutenant commander during World War II.

Sanders six-year overall record at Vanderbilt was 36-22-2. He was SEC Coach-of-the-Year in 1941 finishing with a record of 8-2. His final season as the Commodore skipper in 1948 resulted in another 8-2 record. That club opened the year with a loss to Georgia Tech, a tie with Alabama, a loss to Mississippi and eight straight victories including season-ending wins over #15 Tennessee and #12 Miami (Fla.).

The win over Tennessee was his first in six attempts. Then in January 1949, Sanders shocked the Vanderbilt community with his announcement that he was heading west for the head coaching position at UCLA. It was reported that Vanderbilt offered Sanders a new five-year contract paying $12,000 a year, a guarantee of $10,000 a year until he was 65 years old and retirement privileges of a university professor.

At UCLA, Sanders was offered a five-year contract averaging out to $13,000 a year. Sanders was only 43 years old, but he decided the opportunity to coach at UCLA would be more rewarding. Upon his resignation Sanders said:

“Leaving Vanderbilt, Nashville and the South is not easy. Parting with the Vanderbilt players isn’t either. I’m certain that the university can and will find a highly qualified coach.

“My decision to coach at UCLA was not made hastily. We have played football at Vanderbilt on the highest plane and I wish to thank everyone who has helped to promote it. I want to especially express my gratitude to Madison Sarratt. When Vanderbilt was at its lowest ebb, he had the courage, the wisdom and the foresight to see that this splendid game had a definite place in student and campus life.”

Sanders thrived at UCLA continuing his single-wing offense. UCLA had been playing football since 1919 whereas the major Southern schools were running the pigskin since the 1890’s. Sanders achieved a 66-15-1 record in nine years at UCLA. This includes three Pacific Coast championships and a National Coach-of-the-Year honor in 1954. His 1954 Bruins were 9-0 and declared national champions. This was the Bruins only undefeated and untied football team. This was also UCLA’s only their only national championship.

Sanders began the 1954 season with just 37 players on the varsity and 20 on the junior varsity. He did not stress scrimmaging, but relied on classroom instruction using a strict time schedule. Sanders once said that his players, “Spend only about seven hours a week on the practice field.”

The end of his coaching career would also see controversy. The university came under fire in 1956 from the conference due to the activities of the Westwood Men’s Club, a Bruin booster organization. That group was accused of securing illegal financial aid to the UCLA players.

As a result, the university was suspended and fined by the conference resulting in the senior class losing half a year’s eligibility.

Sanders is credited by Nashville Banner sports writer Fred Russell as making the statement, “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing,” and not Vince Lombardi.

Sanders died suddenly in Los Angeles on August 14, 1958 as he was preparing for his 10th season at UCLA. This is part of the eulogy at his funeral by Paul Wellman:

“In speaking of Red Sanders, we are speaking of a man who chose for his profession one of America’s greatest arenas of unceasing interest–the world of sports–and made it his own throughout his life, with honor, courage, and brilliant success.

“I think of him as an authentic genius–the only true genius I have ever known, although I have known all too many who like to think of themselves as geniuses.

“Red Sanders himself would have been the first to deny such a designation, for among other things he possessed humility that was almost shyness. Yet we have the definition, of the genius by the philosopher, Amiel:

“Doing easily what others find difficult is talent; doing what is impossible for talent, is genius.’

“By that definition, he whose memory we here honor was a great genius, for continually he did the impossible.”

Sanders was inducted into the National College Hall of Fame in 1996.

If you have comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via e-mail WLTraughber@aol.com.