May 6, 2009

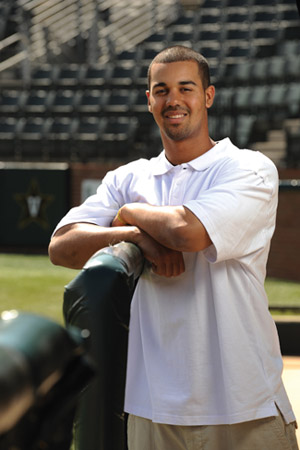

Photo by John Russell

Photo by John Russell

Subscribe to Commodore Nation Magazine / Archive

The popping sound a ball makes when it hits the pocket of a glove, the crackling sound that metal spikes make on the base paths and the distinct sound the umpire makes when he calls a strike. These are just a few of the most distinguishable sounds at a baseball game. They are sounds Joey Manning doesn’t take for granted.

A sophomore outfielder from Bartow, Fla., Manning can hear the sounds and has always been able to, but he knows all too well what it would be like to not be able to hear anything at all.

Manning’s parents, Jeremiah Sr. and Laurie, both are hearing impaired. Laurie was born deaf, while Jeremiah Sr. contracted meningitis when he was three months old, which resulted in his loss of hearing. Because of his experience growing up, Joey has a special appreciation for what he is able to hear.

“A lot of people take their hearing for granted,” Joey said. “I’m really fortunate. Being deaf is a setback, but it is not as bad as it could be. I just always think about what it would be like going to a concert where music is playing loud and hearing absolutely nothing.”

It may be hard for others to relate to how it would be to grow up with parents that are deaf, but for Manning, it is the only way he’s known his entire life. Before Joey could speak English, he could sign. Although he was proficient in sign language at a young age, his verbal skills weren’t up to the same level.

“When I was first growing up, I didn’t know anything different than how my parents communicated,” Joey said. “When I was younger I used to have speech problems a little bit, and that was probably because I was around my parents all the time.”

The middle of three children, Manning’s upbringing forced him to be more responsible at an earlier age than his peers. Joey, along with his older sister Mara (22) and younger brother Jeremy (14), have been counted on since a young age to help their parents with tasks that others would consider just a part of everyday life.

“I just had to learn how to have social skills early because my parents couldn’t talk, so a lot of the time either my older sister or I would communicate for my parents when we were going somewhere,” Joey said. “It would be somewhere as simple as going through the drive thru or going to the bank, we are always with them to help them out.”

Joey’s ability to communicate is something Terrence McGriff noticed right away as his varsity basketball coach at Bartow High School.

“I think that what both his parents being deaf forced him to do is be a great communicator,” McGriff said. “Most kids don’t know how to communicate effectively with adults until they are older, but he was a kid who was able to communicate effectively as a ninth grader. I think he got that because he had to be an effective communicator in order to communicate at home.”

Joey’s ability to communicate also made him a natural leader on the team and helped him earn second team all-county honors in basketball despite not picking up the sport until ninth grade.

“In my 13 years of coaching basketball, he was probably as smart a kid at picking up stuff as any player I’ve coached,” McGriff said of Manning, who was drafted in the 47th round of the 2007 draft by the Philadelphia Phillies, despite already being enrolled at Vanderbilt.

The responsibility Joey had at home with helping his parents communicate also forced him to mature much sooner than most children.

“I was having to communicate with people older than me all the time,” Joey said. “That definitely helped me mature faster. I was having to be independent at an earlier age because my parents weren’t there to help me do a lot of stuff that your everyday parent does.”

To Joey, helping his parents with things others may take for granted and communicating with them through signing was just a normal part of life. He had no reason to believe his relationship with his parents was any different than his classmates. It wasn’t until third grade when Joey realized his relationship with his parents was in fact different.

“The first time I ever noticed (something was different) was when I was in third grade and they had an open house at the school,” Joey said. “My mom actually went with me to that, and I remember seeing everyone’s parents and they were talking to their kids and the teachers. I could communicate with my parents very easily, but it takes a little longer to sign.”

The way Joey communicates with his parents reinforces how fortunate he is to be able to hear. Although his parents’ hearing loss is not hereditary, there was concern that Joey and his other siblings could be born with hearing loss.

“My sister is older than me, and my parents said that they were really worried about her being deaf,” Joey said. “Even though she isn’t deaf, it was still a little nerve-wracking when I was born just to see if it didn’t skip a child.”

Being so involved in helping his parents communicate on a daily basis forged a bond that would be hard for others to relate to. That relationship with his parents made his decision to leave Florida to attend Vanderbilt that much more difficult for Joey. Complicating the decision even further was that the other school he was looking at was Miami. Not only was it closer to home, but it was a school he grew up following.

“Growing up I just loved Miami, and it was really hard for me to not go to Miami with it being closer to home and to come up here, but it just kind of tells how much I like the coaches and the program (at Vanderbilt),” Joey said. “It made it a lot easier to be around people like that in the program.”

For as much as Joey loved the Vanderbilt program when he was going through the recruiting process, the thought of leaving his parents for a school so far away left a knot in his stomach.

“It was pretty tough at first just because, I wouldn’t say I hold our family together, but we have a lot of issues financially and socially that go on in my family,” Joey said. “When I first left, things kind of broke apart for a while, but then things got better and everything is pretty good now.”

Joey admits that at one point last year he thought about transferring to another school so he could be closer to his parents. Part of it was concern for his family and part of it was his lack of playing time. Now in his second season, Joey couldn’t be happier than he is in Nashville.

“I’m really glad that I came up here, and I love everything this program is about … I’ve settled in nicely,” Joey said.

Although Joey is a long way from home and he is unable to have a traditional phone conversation like most children do with their parents, he has found other ways to communicate at a distance. Every day, Manning connects with his parents through e-mail or by using Skype, an online service that enables people to communicate face-to-face on the computer via a Web cam.

Manning may be a long way from his parents, but even when he isn’t connected with them on his computer, the unique sounds that fill the air at baseball games bring his mind back to them.