Jason Esposito Comes Home

by Graham HaysIf coming to Vanderbilt helped Jason Esposito discover what was possible, coming back as an assistant coach lets him return the favor

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — As a son of New Hampshire, Tim Corbin knew families like the Espositos long before he ever filled out a lineup card or sat around the kitchen table on a recruiting visit. Michael and Roseann Esposito and their sons, Jason and Mark, happened to live in Bethany, Connecticut. But from their Italian surname to a no-nonsense forthrightness—not to mention a passion for baseball—they are a New England archetype still far from extinct from Cape Cod to the Connecticut coast.

Nearly two decades ago, those shared New England roots helped Vanderbilt’s head coach forge a bond with the family as Jason, then a highly-touted high school standout, weighed options from college scholarships to MLB signing bonuses. In laying out Vanderbilt’s mission, a lifetime taught Corbin that he would have no greater ally than Roseann.

“A mom looks at it from a unique perspective,” Corbin said. “Baseball is baseball, but who’s going to take care of my kid? Who’s going to watch over him, hold him to a standard, discipline him? I think when moms look at that, they’re not looking at an MLB uniform. For the next three or four years, is the group of people over there going to look after my child?

“A lot of moms up in New England are that way. And in a lot of ways, Roseann was a very firm voice inside that family, making clear ‘No, my kid’s going to school. He could go play professional baseball, but that’s not how my husband and I look at it.’”

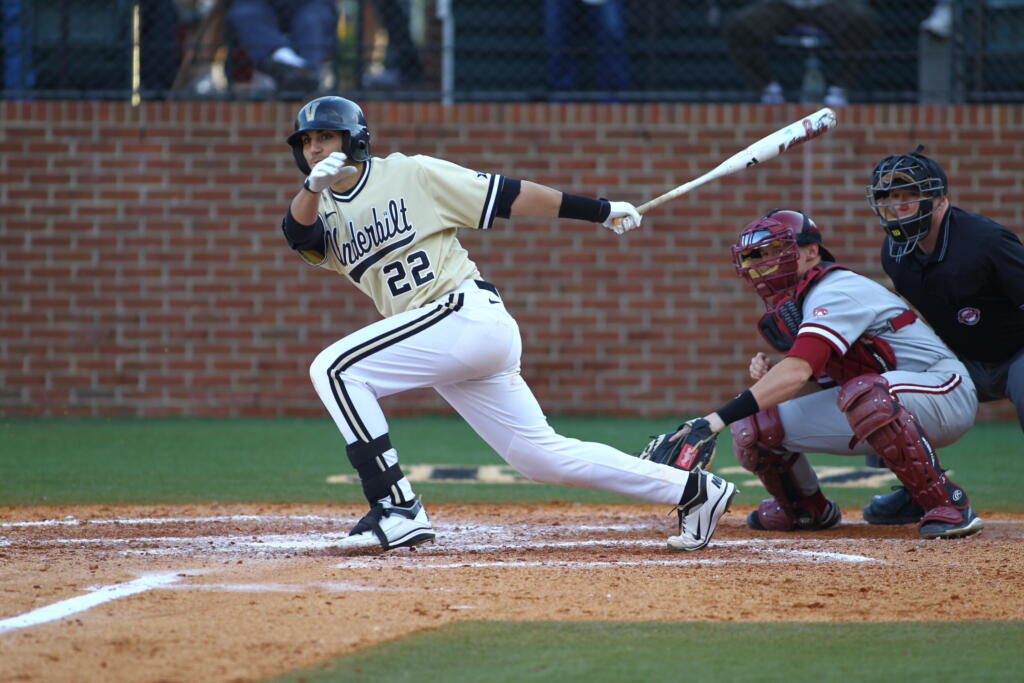

Esposito chose Vanderbilt. He inherited third base from a legend in Pedro Alvarez and emerged as one of the best defensive players in program history. He was an All-American and RBI machine, part of Vanderbilt’s first College World Series team in 2011. What he contributed is easy to find in the record books. What he learned prepared him for the life that awaited—starting a family, finding a calling and always growing. And it’s what he learned here that brought him back to Vanderbilt.

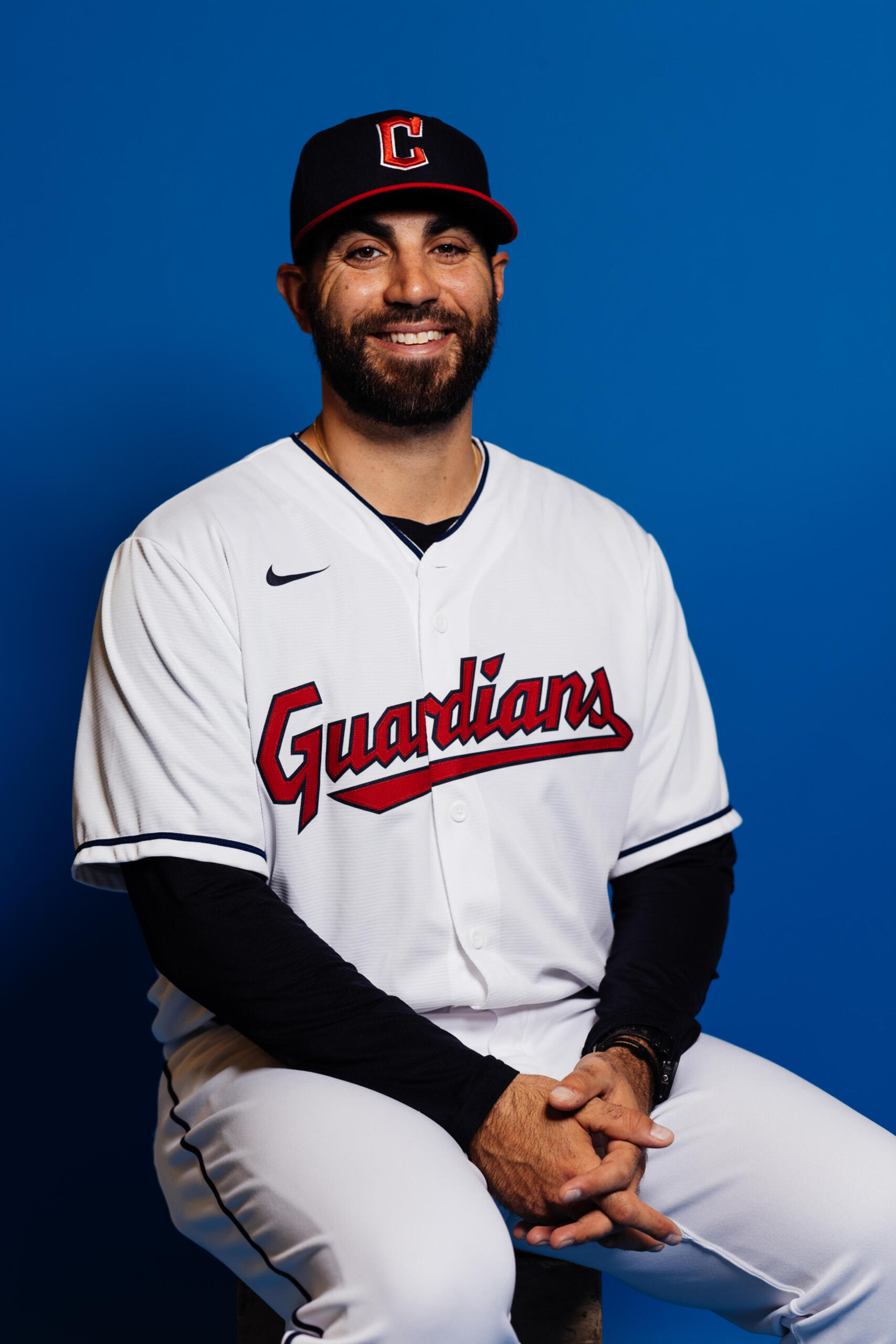

After more than a decade playing and coaching professional baseball, including as a hitting instructor with the Cleveland Guardians for the past eight years, Esposito returns to his alma mater as an assistant coach. If coming to Vanderbilt the first time helped him discover what was possible, coming back gives him a chance to return the favor for a new generation of players sitting around kitchen tables and debating the best path forward.

It’s why, with the possible exception of learning she was going to be a grandmother twice over, Roseann has rarely sounded happier than when her son told her the news this summer.

“She was really happy because she knows who Coach Corbin is—she knows what he stands for,” Esposito said. “She knows Vanderbilt helped me become who I am.”

Becoming a Commodore

All all-everything prep player in Connecticut, Esposito was selected by the Kansas City Royals in the seventh round of the 2008 Major League Baseball Draft. The team was eager enough to sign him that bonus negotiations eventually reached seven figures, nearly $3 million in today’s dollars. He turned down the offer, instead settling into a dorm room and scrounging for pizza money alongside the rest of Vanderbilt’s freshman class that fall.

“I think I had do some self-assessment as a 17-year-old kid and understand that I might not be ready to go off into the world and just play professional baseball,” Esposito said. “I think the best thing at that time was being honest with myself and being honest to my parents—and my parents were instrumental in the decision. They supported me either way, but they also gave me an understanding of what an education means for the rest of my life.”

Fall isn’t easy when you play baseball at Vanderbilt. Under Corbin, fall is when you earn your spring, hotshot draft pick or not. And for someone who had a clearer view of himself with a bat in his hands on the field than a pen in his hand in the classroom, Vanderbilt’s rigorous academic standards were an added challenge all their own. There were a few calls home, questioning just what he had gotten himself into. But as Corbin had promised, there were resources available—all you had to do was accept the responsibility to ask for help.

On the field, the transition to the SEC appeared seamless. Esposito started every game at third base and led the team in stolen bases. He only got better, hitting .359 as a sophomore and leading the team in RBI and the SEC in doubles, then pacing the Commodores in RBI and doubles again as a junior in 2011. That season offered unforgettable moment after unforgettable moment, from his walk-off home run against Louisville in the regular season to the team claiming a share of the SEC regular season title to the super regional sweep of Oregon State that sent the Commodores to their first College World Series.

Yet for all the highlights, collective and personal, few are etched in his memory as clearly as one that wasn’t captured by the cameras. Sitting in the team’s classroom at Hawkins Field early in that campaign, he remembers Corbin writing a record on the eraser board. The numbers didn’t matter. What mattered was the dash in the middle—representing the actions, emotions and accountability that the people in that room controlled.

“It was just the experience with all the boys—with all my friends, teammates—that made the experience so special,” Esposito recalled.

“I think education helped him create a passion and a thought process for learning and teaching. And then because of that, he got into coaching. And then because he got into coaching, he started teaching hitting. He became one of those guys who really loved what he was doing. He had an affinity for the players, and the players had an affinity for him. He grew as a teacher and a coach.”

Vanderbilt head coach Tim Corbin

Finding a Calling to Serve

Looking back on those teams, the signs were there for the next step in Esposito’s journey. Corbin remembers scarcely being able to walk by the batting cages without seeing the cadre of Esposito, Aaron Westlake, Mike Yastrzemski and Curt Casali working with then-assistant coach Josh Holliday, now Oklahoma State head coach. Nearly 15 years later, Yastrzemski is still playing in the majors, Casali just completed a career that spanned 11 MLB seasons and Westlake is a hitting coordinator with the Houston Astros. When it came to hitting, they were relentless, insatiable. And Esposito was very much one of them.

“If they’re in there all the time and they’re spending five and six hours a day, then it would make sense that they’ve invested so much time in it that they probably want to share knowledge,” Corbin said. “That’s where Jason separates himself. He worked hard at hitting and he was a good hitter.”

But if his path is obvious in hindsight, it wasn’t at all clear to him in the moment. He never thought about coaching. Not while playing three seasons at Vanderbilt. Not after being drafted by the Baltimore Orioles in the second round of the 2011 MLB Draft. Not even when he returned to earn his undergraduate degree in 2013 while playing in the Orioles system.

But if his path is obvious in hindsight, it wasn’t at all clear to him in the moment. He never thought about coaching. Not while playing three seasons at Vanderbilt. Not after being drafted by the Baltimore Orioles in the second round of the 2011 MLB Draft. Not even when he returned to earn his undergraduate degree in 2013 while playing in the Orioles system.

In 2015, having retired following four seasons in the minors, like countless former players Esposito was giving hitting lessons and contemplating his next move. He realized that he didn’t want to just go through the motions, telling students what he thought he knew or what had worked for him. He wanted to understand hitting on a deeper level than he had as a player. He was done playing, but he wasn’t done growing. He poured over peer-reviewed research papers on the science behind hitting and videos on biomechanics. He talked to anyone and everyone willing to speak with him about the latest trends.

“It set me down this path of objectivity that really helped shape how passionate I might be for coaching,” Esposito said.

In 2017, he earned an interview with the Guardians and impressed them enough to land a job as a hitting instructor.

He even earned his master’s degree in kinesiology in 2020, with an assist from his wife, Allie—a nurse practitioner who works in an ICU and quickly put him in his place when he expressed doubt about his ability to complete an advanced degree.

As Corbin put it, “there’s no way in hell” anyone would have predicted that an 18-year-old Esposito was on his way to a master’s degree. He just wanted to play baseball. And even Esposito would agree that baseball remained his primary passion at Vanderbilt. But in addition to grinding through the litany of required classes, he also had the freedom to choose others. Sure enough, able to pick subjects that interested him and teachers as passionate about conveying the information as he was about playing baseball, he grew more attentive, focused and intentional in his work—engagement that has proved as useful in his subsequent coaching career as all those hours in the cages with Holliday.

“I think education helped him create a passion and a thought process for learning and teaching,” Corbin said. “And then because of that, he got into coaching. And then because he got into coaching, he started teaching hitting. He became one of those guys who really loved what he was doing. He had an affinity for the players, and the players had an affinity for him. He grew as a teacher and a coach.”

Coach Esposito Returns

Esposito served in a variety of roles in the Guardians organization, including hitting coach for Class-A Mahoning Valley and Triple-A Columbus and, most recently, run production coordinator and assistant hitting coach with the big league club. A product of what amounts to baseball’s bridge generation, as analytics expanded from a revolutionary movement most famously portrayed in Michael Lewis’ Moneyball to mainstream adoption, the tools and technology more widely available by the year were a natural fit for a young coach committed to studying every nook and cranny of hitting.

“He’s been knee deep in the offensive side of the game, hitting,” Corbin said. “I think hitting has changed quite a bit, with the analytics and numbers and thought processes that go behind hitting. I think in today’s world, players and coaches look for that guy who is really passionate about hitting but really involved in it enough to where they’ve studied it and can apply it in teaching terms to a young person. That’s where I felt like he had an advantage.

“When that happens, I think you build some trust with the kids because they want to know about that. They want to know how to change angles, create barrel awareness, they want to develop a plan. They want the things that he potentially can provide them.”

Still, Esposito stresses, information is one part of the equation. It’s only a tool, only as valuable as a teacher’s ability to communicate its lessons. The satisfaction, even the joy, in his job isn’t in the data. It’s working with someone to develop a plan that puts them in the best position to succeed, then seeing them follow through—seeing the realization in their faces of what all the work was about, even if it’s a line drive right at the centerfielder.

It’s easy to see the joy in Esposito’s walk-off home against Louisville all those years ago, the solitary figure sprinting toward the plate enveloped by and indecipherable from the mass of waiting teammates. It’s the joy of victory. You play to win. You play to win it all. But that moment is also about the group and what’s possible—the dash in between the wins and losses.

As a coach, you aren’t in the dogpile at home plate after the walk-off home run. You’re probably already worrying about the next day’s starter. But you’re part of it all the same.

“I think the goal changed from wanting to be the best player I could be to wanting to see the players I have the opportunity to coach be the best that they can,” Esposito said. “I always try to keep that at the forefront. It’s about the boys, really. It isn’t about me as a coach. Having them reach their goals is the new way of me hitting a home run.”

Nearly two decades after he trusted a baseball program and a university to show him where life could take him, it led him back to Hawkins Field.

Sometimes moms know best.