April 8, 2015

Commodore History Corner Archive

Commodore History Corner Archive

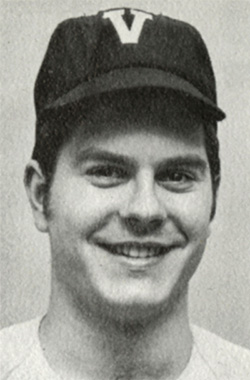

Former Vanderbilt pitcher Elliott Jones (1968-70) was not only the first Commodore to be selected in the Major League Amateur draft but also the first to be drafted twice.

“Back in those days they had two drafts,” Jones said recently. “It is different now because after my third season I could not be drafted since I was not yet 21 years old. You had to turn 21 before your junior year to be eligible for the draft.

“I would not have been 21 until October of my senior year. I was not eligible to be drafted in the June draft of 1970. I was eligible for a spring draft in 1971 and selected in January (sixth round, 101st overall) by the Red Sox. I basically didn’t sign because of money. Then I was drafted by Pittsburgh in June (12th round, 293rd overall). I had already graduated Vanderbilt in January.”

The right-hander played his high school baseball at Nashville’s Montgomery Bell Academy. MBA was a member of the old NIL (Nashville Interscholastic League) and did not have an on-campus baseball field. The Big Red played their home games and practiced at West End Junior High, Centennial Park or the baseball diamond in Percy Warner Park out by the Steeplechase.

“None of those diamonds had fences,” Jones said. “The big difference pitching wise in high school today and back then was no pitching machines. The only batting practice you got was someone throwing to you. I never pitched behind a pitching screen on the mound in high school or Vanderbilt until I was in pro ball. You wouldn’t pitch today without a pitching screen.

“When I was called to pitch batting practice at Vanderbilt, hitters wanted to hit and I just wanted to survive. We would never throw the ball over the plate. We would throw inside so they’d pull the ball. We did not want them to hit the ball up the middle. We had a kid named Jeff Love, a fine player that hit .374 one year. He would hit the ball right up the middle in every game. When Jeff was up in practice we were not going to throw him anything near the plate. The batters were getting frustrated at us.”

The Tennessean named Jones the NIL MVP as a senior for his pitching and leading the league in home runs and RBIs as an outfielder. The evening newspaper, the Nashville Banner, named MBA sophomore Jeff Peeples its NIL MVP. Peeples would later gain a scholarship at Vanderbilt and become one of the most dominant pitchers in program history. John Bennett was the MBA coach at the time.

Jones’ father, Ernest, was a physics professor at Vanderbilt and Chairman of the Vanderbilt Athletic Committee. Tennessee, Davidson and Cornell recruited Jones. At the time, Jones received 100 percent free tuition since his father was a member of the Vanderbilt faculty. The university did not offer baseball scholarships at the time. Said Jones: “My father would have had an early grave if I’d gone to Tennessee. Vanderbilt just seemed to be the place for me. I went to Vanderbilt and lived at home.”

Vanderbilt has been playing baseball since 1886. The Commodores had never won a conference championship and often finished in the bottom half of the standings. It was Jones’ father that can be credited with a surge in Vanderbilt baseball success with the school’s hiring of Larry Schmittou (1968-78).

“Jess Neely was the athletic director and George Archie was the baseball coach,” Jones said. “My dad worked on the Manhattan Project in New York and was a nationally known physicist. (Ernest Jones turns 97 in June). As Chairman of the Athletic Committee he wanted to get a new baseball coach since I was coming to Vanderbilt. He went to Neely and said his son is coming and is a pretty good baseball player and he thought Vanderbilt needed a better coach and program.

“Coach Archie was only a part-time coach. Neely basically said that is a great idea why don’t you find one? My father asked John Bennett, who played baseball at Vanderbilt and was my high school coach, if he’d be interested in the job. He looked at my father like are you insane? Why would I want to leave MBA to coach Vanderbilt baseball? So that didn’t work.

“Then he approached Larry Schmittou who coached me in the summer (Connie Mack League). On that summer team there was me, Wayne Garland, Jeff Peeples and Mike Willis. Garland won 20 games in the big leagues. Willis played on and off in the big leagues and Jeff would have been a big league pitcher had it not been for a car wreck.

“Then I had two undistinguished seasons in the minor leagues and went to law school. We finished third in the Connie Mack World Series. Larry coached those teams. Neely offered Larry $1,500 to coach that spring. Here was a physics professor representing Vanderbilt athletics trying to hire a baseball coach with $1,500.”

Schmittou became a baseball icon to Nashville. He was born in 1939, and grew up in West Nashville where he graduated from Cohn High School and George Peabody College. Schmittou coached sandlot baseball throughout Nashville and would eventually change the landscape of Vanderbilt baseball with his arrival in 1968.

“I came in as a freshman in Schmittou’s first year,” Jones said. “He wasn’t hired until about January so we had gone through fall practices (without Schmittou) for freshmen that wanted to come out at Centennial Park. I went to a couple of practices and thought this wasn’t going to work. When Larry was hired there was only about three weeks before the season started.

“We played on what is now McGugin Field and sometimes we played at Centennial Park. Centennial Park had lights, but our field did not. Neither field had a fence. We would hit balls into the glass where the swimming pool was in the basement of Memorial Gym. In my freshman year they practiced football in the spring on the baseball field. They installed lights with posts similar to telephone poles to practice at night. They were three or four poles sitting in the outfield.

“One of them was probably 30 feet back from where the infield grass ended. Once we played Kentucky and Mike Mease, one of our better batters, hit a line drive. A Kentucky player ran into the light pole chasing the ball. The ball just kept rolling since there was no fence. We beat Kentucky because their outfielder ran into a light pole. Football spring practice was going on and they didn’t care about baseball.”

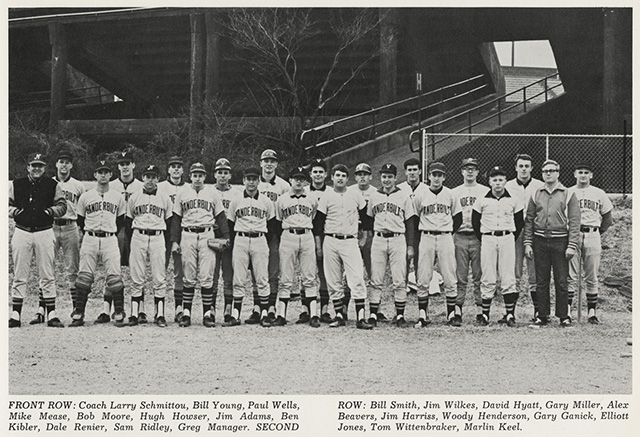

In Jones’ first season the Commodores were 7-15 and 2-13 in the SEC, finishing in last place. There were no scholarships offered at the time. The SEC was divided into two divisions and the Commodores represented the Eastern Division with Tennessee, Kentucky, Auburn, Florida and Georgia. The SEC began playing in a two-division format in 1959.

“We didn’t play anybody in the Western Division,” Jones said. “We played a three-game series with a game on Friday and two games on Saturday. We didn’t play on Sunday. Most of the time we traveled to games in our own cars. I remember going to a game in Memphis in my dad’s car with three other players. After the game Schmittou would tell us, `Be careful driving back and don’t stop to get anything.’ That was his warning to us to behave. It was not unusual for us to operate like a summer baseball team.”

Jones said he was in the the first pitching rotation under Schmittou, along with Paul Wells, Jim Wilkes and Jim Adams. Said Jones: “It was a good group, but not a distinguished group.” The 1969 team was 21-18 and 3-10 in the SEC with an expanded schedule. Mike Willis was Schmittou’s first scholarship player and would be joined by Steve Estep and Bill Winchester. Jones led the SEC in strikeouts (112) and was named to the SEC All-Eastern Division team.

“It was not a bad team because Mike (Willis) was there as a freshman,” Jones said. “With Estep and Winchester, Larry just figured out how to get these local guys into school with some financial aid. The 1969 team was very competitive. It didn’t show in the SEC record, but substantially better than the year before.”

The 1970 team was 24-16 and 5-10 in the SEC. The starting rotation revealed Willis, Doug Wessell, Jones and Peeples. Peeples also played on the Commodore football team. Jones said that Wessell threw an incredible curve ball.

Jones tossed a no-hitter at Kentucky, but lost the game in the 10th inning. The game was scoreless after nine innings until a three-run Wildcat home run ended the game. At the time, Jones was leading the SEC in strikeouts and was coming off a loss to Florida where he pitched a two-hitter.

“It was one of those years where everything went wrong,” said Jones. “I was supposed to be a leader since I was a returning All-Eastern Division and SEC strikeout leader. I pitched nine no-hit innings and in the 10th inning it goes away.”

The talent did improve for Vanderbilt baseball and there was a view of optimism for the future under the guidance of Schmittou.

“Our view of Vanderbilt baseball was more localized,” Jones said. “We didn’t play but half of the SEC. There was no SEC baseball tournament. It was very small-time. Thinking about the stadiums… Tennessee just had bleachers, as did we. At UT the fraternity houses were up on a hill so they would scream and yell at us the entire time we were there. The stadiums looked like Shelby Park a few years ago with a nice diamond and basically bleachers. I don’t think there were any exceptions to the SEC stadiums with just bleachers. We never played in any real stadium.”

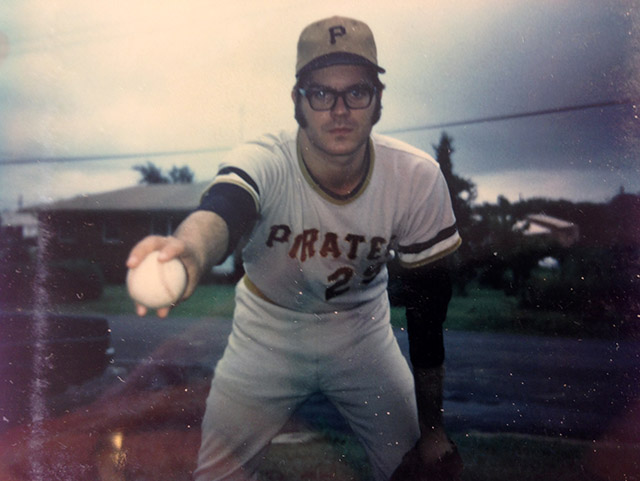

Jones decided to skip his senior year of baseball to prepare for the Vanderbilt School of Law. His Vanderbilt career pitching stats are unavailable. When Jones was drafted in 1971 by Pittsburgh, he put his law studies on hold in an attempt to pursue a possible career in professional baseball.

At that time the minimum salary for a big league ball player was just $12,750. Roberto Clemente was the top Pirate with a $125,000 a year contract. The Pirates won the 1971 World Series in seven games over the Baltimore Orioles.

“I signed for $6,000,” said Jones. “I remember standing in Pirate City (Bradenton, Fla.) in the spring of 1972 watching Nelson Briles and Steve Blass trying to negotiate a contact for $55,000 and $65,000 a piece. They were both holding out during spring training in 1972 after they won three games in the 1971 World Series.

“I received $6,000 broken into two bonuses. One was $3,000 when I signed and one was $3,000 in September. Back then $3,000 would buy me a new Pontiac Grand Prix, which it did. I was sitting in Pirate City in winter ball with several kids, like Dave Parker, that were going to be on 1979 Pirates World Series club.”

Jones played two seasons (1971 and 1972) in the Pirates organization and was impressed with the athletes he competed with. His two-year minor league totals include 26 games (13 starts) with a 4.40 ERA in 94 pitched innings while giving up 85 hits and 51 runs (46 earned).

“When I first signed I drove straight to short-season training in Bradenton,” he said. “Then I was assigned to Monroe, N.C. (Class A Western Carolina League) where they put us up in the Holiday Inn. Walking out of the motel was a 6-foot-5 black guy wearing a tank top that looked like the finest athlete you’d ever seen in your life and he was wearing a Pirates’ hat.

“I thought if they are all like this I am in real trouble. It was Dave Parker who was playing with us in Monroe. He was 19 years old from Cincinnati. Mario Mendoza was our shortstop and Ed Ott was also on that team. Then I went to Niagara Falls (Single-A New York/Penn League). I played instructional league ball in Florida during the winter. There I gave up home runs to Dwight Evans and Jim Rice in the same game.

“I came back in 1972 to Single-A in Gastonia (Western Carolina League) and had the combination of an arm injury and being accepted into the Vanderbilt School of Law. I played part of the season and decided to go to law school. They held me on the Triple-A roster for about 10 years after I left. I asked why in the world would they have me on the roster. I was told they wanted to make sure I didn’t come back. I told them that was unlikely. They wanted to keep my rights. I told them they must really be desperate.”

Jones has a son Warner that played for Vanderbilt from 2003-05 where he was First Team All-SEC and an All-American in his final season as a Commodore. Warner has the fourth best batting average (.414) in Commodore history and holds single season records for hits (111), doubles (27) and RBIs (74). He was drafted by Detroit (17th round, 510th overall) in 2005.

“Warner never signed,” said Jones. “He had a wrist issue for most of his final year at Vanderbilt. He shattered his wrist in the Cape Cod League and had some tendon problems. In his two years in the Cape Cod League he led the league in hits both years. He played his last year at Vanderbilt with that wrist problem and had to have surgery. The Tigers offered him about $100,000, but they wanted a waiver (that) if proved he was injured in a physical they could take it back. We knew he was injured and we couldn’t reach an agreement.

“Warner got into law school. It is one thing for a pitcher to go out and have a few good innings and get to the big leagues pretty quickly. A position player that is small in physique has to prove himself in three or four years. That is a long time for a kid that is smart enough to get into law school. He made that decision. There is no doubt in my mind that Warner could have played in the big leagues and been an all-star. It just didn’t happen.”

Elliott and Warner are both attorneys working for Emerge Law in Nashville. In 1971, the Commodores won their first of four consecutive SEC Eastern titles. In 1973 and 1974, Vanderbilt captured the SEC championship and Schmittou was named SEC Coach of the Year both times.

Schmittou coached 20 All-SEC players while 14 were taken in the major league drafts. He is currently ranked third all-time in career wins with a mark of 306-252-1 behind Roy Mewbourne (655-608-9) and Tim Corbin (517-250). In 1978, Schmittou brought professional baseball back to the city with the Southern League Nashville Sounds as part owner and president.

“There are two things about Schmittou you have to understand,” said Jones. “He is not smart enough that when someone tells him you can’t do this, that you really can’t. If you say it’s impossible, he doesn’t know it’s impossible. He didn’t think anything was impossible. There is no job that is too small for him to do himself. If the restrooms needed cleaning in Greer Stadium at three o’clock in the morning Larry is going to clean them out.

“The things that made Larry special was he was never going to give up. He kept going until he got a `yes’ or he was going to wear you down. Nobody could ever accuse him of not doing what was needed to be done. He was coaching us in the daytime and working at the Ford Glass plant at night to support his family.”

If you have any comments or suggestions contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.