A Father's Lessons Live On

by Jerry StackhouseGeorge Stackhouse didn't just tell me about the value of hard work. He showed me every day of his life.

The invitations to go fishing didn’t always come with advance notice. And if I wasn’t paying attention, I was out of luck. My dad wasn’t a man who asked you a question twice.

Not that he ever had to when it came to fishing. I was always ready. I remember rushing to put on a long-sleeved shirt and pants. In the middle of a North Carolina summer, you hoped the fish were biting, but you knew the mosquitoes would be. Even now, that distinctive scent of mosquito repellent fills my nose just thinking about those trips.

We’d always stop in town at the 76 Mini Mart, the one that had the bait shop attached. We’d buy our worms and corks, maybe a new cane pole. We usually headed to the Neuse River, which runs right through Kinston. But you never knew. My dad loved nothing more than scouting out some new fishing hole in the woods that no one else had discovered.

Sometimes we would talk once we got settled, but we were there to fish. Keep your eyes on your line. I definitely recall him telling me, “You talking too much; the fish aren’t going to bite.”

Don’t get me wrong—my dad could come up with words of wisdom. That man had his sayings. My wife will tell you they live on to this day, even if I don’t always realize I’m repeating them. But the memories that remain etched foremost in my mind aren’t anything he said as much as what he did. Doing was George Stackhouse’s default state—working, providing, protecting. And yes, when he could, fishing for perch, catfish or eels (I never could stomach the eels).

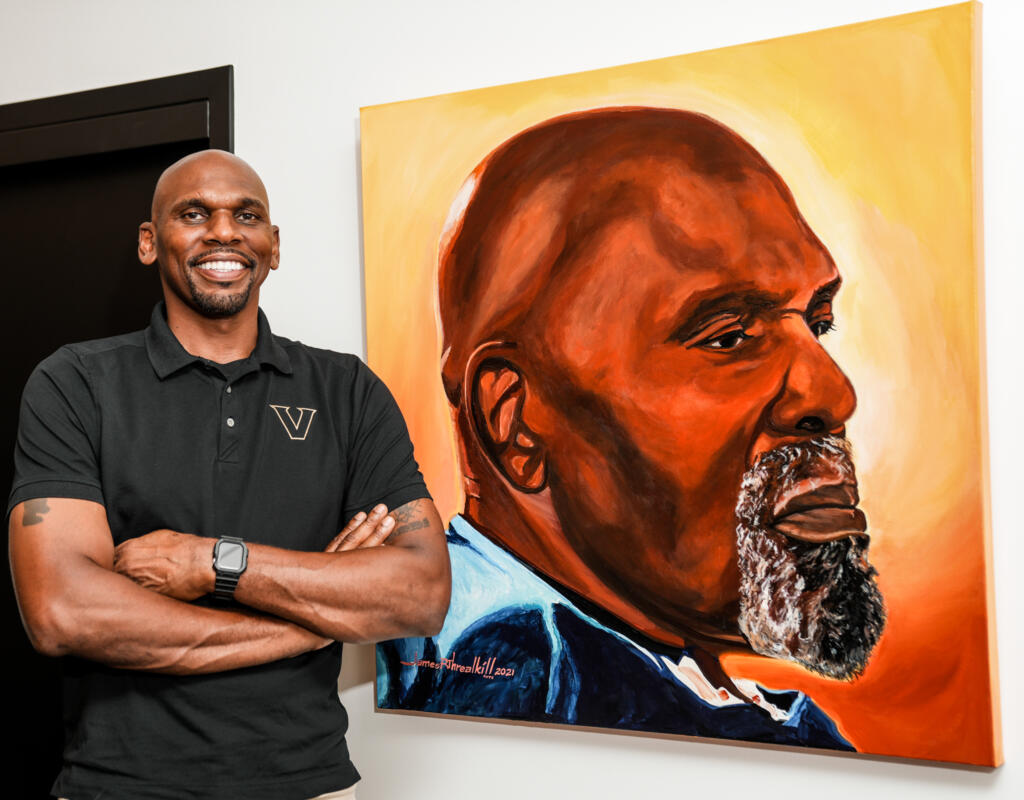

Jerry Stackhouse keeps a painting of his father – George Stackhouse – in his office at Vanderbilt. The painting was created by Vanderbilt alumnus James Threalkill.

A man’s got to do what a man’s got to do. That was one of his favorite lines to live by.

I wish my dad was here for Father’s Day. I still miss the hell out of him. But for my family, my friends and the student-athletes, coaches and staff who form our Vanderbilt basketball family, I try to honor him every day by living up to the example he set—I try to honor him by doing what I learned from him.

My dad didn’t need to tell me how to work hard. He showed me every day of his life.

In the 25 years he worked as a sanitation driver, I don’t know if he was ever late. He was one of those guys. He would be up before dawn and out the door before the rest of us were awake. But that was only one of the ways he provided for us. He was always doing all types of odd jobs. He was a mover, landscaper and bricklayer, among other things. He even had his own tree removal service. Saturday wasn’t the weekend—it was just a different workday.

Any work ethic I have comes from both my parents, but especially my dad. He hauled me along with him for some of those jobs, even if I didn’t look forward to those mornings nearly as much as the fishing trips. The only heat in his old pickup came out of the floor vents, so on cold mornings in fall and winter, the rest of your body was out of luck. Like the mosquito repellent, that’s another sensation that lingers years later—the feeling of curling up on the floorboards when we got to a site and catching a few extra minutes of sleep while he got things organized.

He didn’t treat me as free labor. He expected me to work like any of the adults on a job. But when I went to work for him, he paid me like the adults, too. At 8 or 9 years old, after loading tree limbs in the back of the truck or bagging grass clippings from the push mowers, that was my first time having money in my pocket. It was my first time accomplishing something and getting the reward for it. My first time doing something with purpose.

I’m not going to lie. Watching him work also spurred me on to work on my jump shot because I knew I didn’t want to do that my whole life. He grinded hard. He didn’t even cash the checks, just gave them to my mom to handle and went on to the next job. But those experiences gave me confidence to know that no matter the situation, I could earn and provide for my family.

As I got older, we had some clashes. I was becoming a man and ready to step out and make my own decisions. I might not want to tell him every time I was coming or going. But my dad, if you lived in his house, you needed to let him know when you’re coming and when you’re going.

That’s just the natural butting of heads between a father and son. When maybe you’re not quite as much of a man as you think you are, but you’re more of a man than he thinks you are.

My dad was a hard man—even the toughest guys I knew always straightened up in his presence and called him “Mr. Stack.” When he was around, you didn’t curse and you went to church on Sundays. But we grew through any battle of wills. We grew closer because of them as we aged. It’s funny, once I had kids, I remember how gentle and loving he was with his grandkids. Sometimes I had to stop and laugh, asking myself, “Do I remember him being like that with me?”

Plant a butterbean, you get a butterbean.

That was another of his favorite sayings. I think about it sometimes when I see myself in a picture. There’s no mistaking where that head shape came from. That’s a George Stackhouse original. I hope it isn’t the only similarity. I always felt safe when my dad was around. Not just physically safe but secure. If he was there, I knew our family could get through anything.

I always wanted my children, and now our team, to feel that same sense of security. I want them to trust that I’ll do what I need to do for them and give them a chance to thrive.

As I got older, basketball started to get in the way of impromptu fishing trips with my dad. But even if I was at practice or playing a game somewhere, friends would tell me when they saw him out with his cane pole, trying to get the fish to bite. Doing that was part of who he was.

I’m thankful that later in life, when I could help him and my mom, we had time to fish together again. No one loved those opportunities more than my son Jaye. I liked fishing, but the two of them shared a passion, so much so that Jaye just got back from a fishing trip in the Bahamas.

In small ways like that, my dad is still with us. I do my best to ensure it isn’t the only way.

A son’s got to do what a son’s got to do.