Stroke of Inspiration

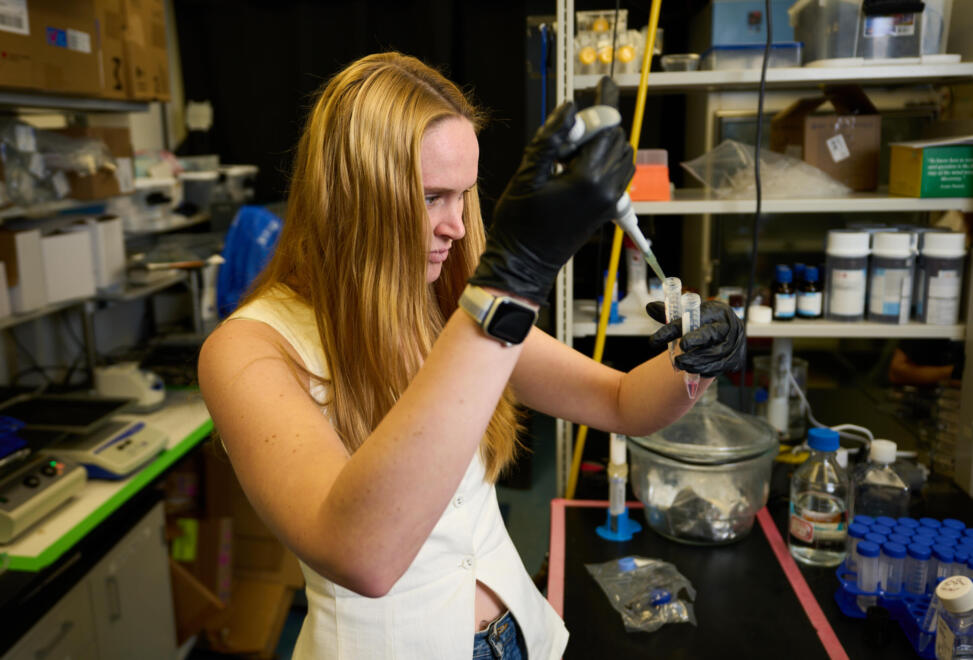

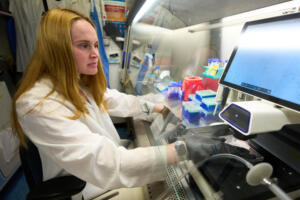

by Graham Hays with photos by Garrett OhrenbergSwimmer and Ph.D. student Jojo Pearson’s tissue engineering research could help in fight against neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — As the daughter of a former collegiate swimmer, Jojo Pearson has been around pools as long as she can remember—even longer than she can remember, in fact. As the story goes, she was barely old enough to walk the first time she showed an inclination to launch herself into the water. Supportive of her spirit of discovery, if not the planning and execution of the experiment, her dad quickly signed her up for swimming lessons.

Pearson proved a precocious learner. She’s now a Vanderbilt graduate student in her final season of eligibility after completing four successful seasons at Case Western Reserve. But the thirst for knowledge that first propelled her into the pool—and back into the water this season after a year away from the sport—isn’t limited to athletics. Pearson boldly confronts the unknown in ways that may shape the world well beyond SEC pools.

As she readjusted to the demands of life as a student-athlete this fall, Pearson made a different sort of road trip. She went to Baltimore for October’s Biomedical Engineering Society Annual Meeting, where the second-year Ph.D. candidate in interdisciplinary materials sciences presented an abstract on research related to neurovascular coupling.

Leading the research alongside adviser Leon Bellan, associate professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering, Pearson’s work has helped secure a grant from the American Heart Association. Her research could help the biomedical community better understand neurodegenerative disease progression and test the efficacy of new drug treatments.

Pearson’s future beyond competitive athletics is already taking shape, and she didn’t need to return to swimming this year. But her past in the pool and future in the lab are parts of the same story: One helps explain the other, and they fuel her desire to work toward a common goal and be better today than she was yesterday.

“With swimming, it’s a lot of trying again and again and again and being very comfortable with failing until you get to where you want to be,” Pearson said. “It’s very similar with research, where you’ll have an experiment fail a hundred times and you keep changing little things and trying to get it better. Eventually it works, and it’s really, really rewarding when it does.”

"One of the first things that struck me is her willingness to really get into the literature to understand what’s going on and her results. That’s not something that a lot of younger students will do, particularly independently."

Leon Bellan, associate professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering

The Human Face of Research

Pearson left her native Southern California for Ohio’s Case Western Reserve because she wanted a challenging academic environment and a change of scenery. She didn’t fully account for winters along the shores of Lake Erie. Wind chill and snow boots aside, she enjoyed the experience as a biomedical engineering and neuroscience double major. The small-to-midsize academic environment (not unlike Vanderbilt) afforded her ample research experience. She had known entering college that she wanted to work within the convergence of medicine, biology and engineering. At Case Western, she had the time and freedom to explore paths that lead there. Instead of a stereotypically impersonal lab environment, she discovered the potency of seeing research affect everyday lives.

As a junior, she worked in a neuromodulation lab, where researchers helped amputees control prosthetics using the nerve signals from their residual limbs. Pearson worked with a veteran who had lost both arms.

“He was able to hold his daughter’s hand for the first time ever,” Pearson recalled. “I literally saw the tears in his eyes. That was the biggest moment I’ve had as a researcher.”

Pearson set a personal best in the 1,000 free on Nov. 22 (photo by Joe Howell/Vanderbilt Athletics).

New Chapter in Nashville

Interested in pursuing graduate research, Pearson applied to a number of material science programs that focused on biomaterials. After four Ohio winters, she figured she would end up close to home. But she visited Vanderbilt, and the more she learned about its unique program, the more a less transcontinental move appealed.

She was accepted into the School of Engineering’s Interdisciplinary Materials Science program, which brings together more than 40 full-time faculty members and an individually customizable curriculum. She moved to Nashville ahead of the 2023–24 academic year.

“It really felt like the faculty and staff were invested in the students’ success in the program and really cared about you,” Pearson said.

First-year students in the program complete three lab rotations over the first two semesters, in addition to taking classes and serving as teaching assistants. At the end of the second semester, each student continues on in one of those labs. In Pearson’s case, that meant joining Bellan’s lab with its emphasis on tissue engineering.

“She’s very independent, super hardworking,” Bellan said. “One of the first things that struck me is her willingness to really get into the literature to understand what’s going on and her results. That’s not something that a lot of younger students will do, particularly independently. They might do it after I ask them to. But when she gets results that require further explanation or context, even before talking to me, she will look into the literature and find the one or two papers out there where people have done things that are relevant so that we can better understand our system. That’s pretty rare.”

Research That Makes a Difference

Bellan’s previous work includes pioneering efforts to create artificial human capillary blood vessels using cotton candy and gelatin. Recently, his lab’s work has also focused on resistance vessels, the blood vessels that make themselves larger or smaller to redirect blood flow around the body as needed.

Pearson, with her background in neuroscience, arrived at the ideal time to take the lead on an idea that Bellan had been contemplating about resistance vessels and the brain.

Different parts of the brain require different levels of blood flow at different times. As more neurons fire in a given part of the brain, nearby blood vessels get bigger to deliver more blood flow and energy. This relationship is neurovascular coupling, “the close temporal and regional linkage between neural activity and cerebral blood flow.”

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, neurovascular coupling gets muddled. Pearson’s project seeks to use stem cells to model a portion of neurovascular coupling—a working three-dimensional model is far more accessible to study than a living patient’s brain, and it’s more cost effective, accurate and ethically uncomplicated than animal testing.

“We’re looking at the interface between neurons and vasculature and making a tissue engineering model of that,” Pearson said. “That’s the end goal, so people can look at different disease progressions and also test and develop different drugs to see if they’re safe and effective.

“A big part of the motivation behind this is to give other people a platform to research different therapeutics that might help treat these different diseases that are associated with neurovascular dysfunction.”

October’s presentation at the conference in Baltimore represented roughly a year’s work in the lab, with substantive progress and positive data to report about growing and sustaining the cells used in the modeling and finding the enzymes necessary to move forward with the research.

Several thousand people attend the annual conference. While not all of them had reason to pay attention to her particular place in the proceedings, it was an important professional development opportunity. Not that someone used to standing on the starting block was likely to suffer from stage fright.

“I definitely get much more stressed out about swimming than I would just going to a conference and talking about my research,” Pearson said, chuckling. “At the end of the day, you’re supposed to be an expert on your research. So no matter what people ask you questions about, they’re going to take you as an authority. I find a lot of comfort in that, whereas with swimming, anything could happen and you don’t really know what the person next you is going to do. You have to really just focus on you, on your own race.”

Paying It Forward

Pearson didn’t intend for swimming to be part of her Vanderbilt story. She had eligibility remaining after losing more than a full season of competition to the COVID-19 pandemic, but she was solely a graduate student during her first year in Nashville. She didn’t want to feel overwhelmed. And spending roughly 40 hours a week in the lab, on top of other academic responsibilities, made plenty of demands on her time.

But as her second year approached, she felt drawn to the pool. She had played a variety of sports growing up, but she was never far from water. With swimming, she enjoyed training at least as much as competing—maybe more. She loved the team dynamic in training, people pushing you to be your best and supporting you regardless. So, with head coach Jeremy Organ’s support in working around her schedule, she debuted in Division I.

Just before Thanksgiving, a month after her conference and with exams looming, she set a personal best in the 1,000 free at the Gamecock Invitational.

“I think there’s been a shift in tone where it’s like this is something I get to do, not so much something I have to do,” Pearson said of swimming again. “As an undergrad, for a while, I think I sometimes had the mentality that it was something I had to do. I definitely didn’t enjoy it as much because of that.”

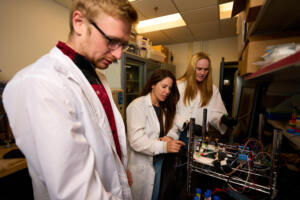

Team still drives her forward—the camaraderie she felt with the people in Bellan’s lab was as much the impetus for choosing it as the specific research she would be doing. And in addition to lending a voice of experience to her swimming teammates, she’s supervising undergraduate students in their research. It’s rare, in Bellan’s experience, to have a second-year student who is both settled enough in their own project and eager enough to mentor to take on that role.

“I was really fortunate to work with really amazing grad students as an undergrad doing research,” Pearson said. “Being able to return the favor was a big priority for me in grad school—mentoring kids and getting them excited about research and getting them in the lab. I wanted them to get hands-on experience with what exactly does it mean to do research in an academic setting? That mentorship was important to me.

“Dr. Bellan does a great job of finding students who are interested in doing research and getting them in the lab.”

She’s there with a helping hand for those who share her desire to explore the unknown. Just as her dad was all those years ago when she wanted to find the answers in the pool.