Dec. 2, 2015

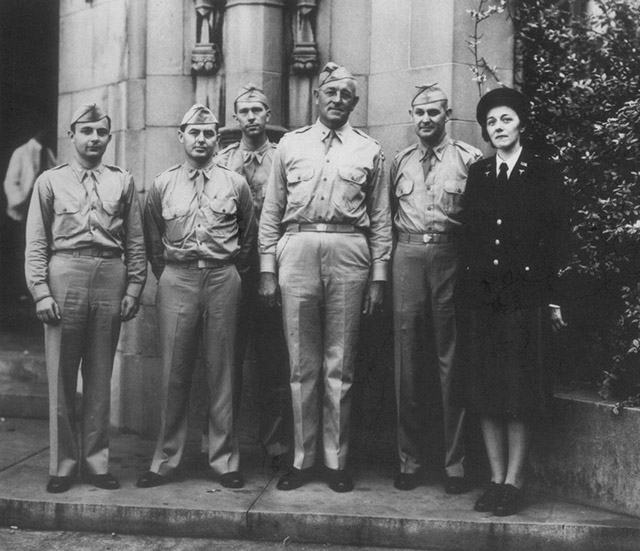

Officers of the Vanderbilt University 300th Medical Hospital Unit prepare to leave for duty on the Italian front during World War II.

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in part to a Joint Session of the United States Congress one day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

Later that day, Congress declared war on Japan with Roosevelt signing the resolution. Two days later a similar resolution declared war on Germany and Italy, as the war in Europe had been ongoing since September 1939.

In the December 7, 1941 edition of Nashville’s daily newspaper, the Tennessean, the first sports page has a photo of Vanderbilt head basketball coach Norman Cooper (1941-43, 1946-47) giving instructions to his center Homer “Red” Dehoney, who is sitting in a chair shooting a basketball in an unusual drill. Cooper was also an assistant football coach for the Commodores as it was a tradition at Vanderbilt and most colleges in that era for assistant gridiron coaches to lead the basketball teams. Vanderbilt would hire its first full-time basketball coach, Bob Polk, in 1947.

The additional story to the photo refers to Dehoney as the new Vanderbilt center who was a transfer from David Lipscomb, which at the time was a two-year college. The Commodores had just begun practice sessions and regular season games were not scheduled until January. Life at Vanderbilt and Nashville were normal until the next day.

The headlines for the Tennessean’s special early edition on the morning of Dec. 8 read:

JAPS ATTACK U.S. BASES!

HAWAII, MANILA ARE BOMBED: HEAVY LIFE LOSS REPORTED EXTRA

In that same issue in the sports section, a story is told of Vanderbilt’s basketball squad expanding to 20 players with the addition of Commodore football players trying out for the team.

That evening the Hermitage Hotel was host to Vanderbilt’s annual football banquet. Twenty-seven letters were awarded while Fred Holder (center) and Jack Jenkins (blocking back) were named as captains for the next football season.

The 1941 football team was 8-2 (SEC 3-2) with the final game played November 29, a 26-7 loss to Tennessee in Knoxville. Red Sanders, a former Commodore football player, was in his second year as the Vanderbilt head coach. No war news would appear in the sports section until days later.

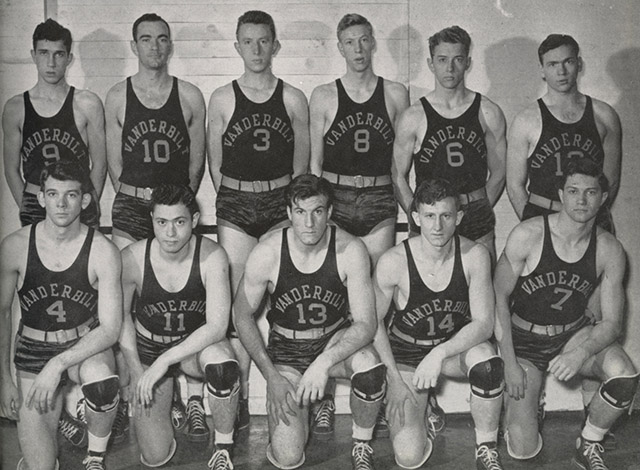

The 1941-42 Vanderbilt men’s basketball team.

Legendary sports writer and Vanderbilt graduate Fred Russell wrote in his “Sidelines Sidelights” column for the Nashville Banner (the city’s evening newspaper) dated December 8, 1941:

Sports—And War

“Last night, in the middle of a movie, the film suddenly stopped. The lights came on, and a soldier—an “MP”—stepped from the wings, saying: “Excuse me for interrupting, but will all members of the Fourth Depot Squad of the Army Air Corps report to their post at once.”

“He repeated: All members of the Fourth Depot Squad of the Army Air Corps report to their post at once.

“That was all. The movie resumed.

“Wasn’t much laughter thereafter. Frequent whisperings. The war had been brought closer than ever by the announcement. It was difficult to concentrate on the movie, to thoroughly enjoy any kind of entertainment.

“With the war clouds that formed long ago now rumbling thunder and flashing lightening, with the United States attacked, sports may seem out of place at the moment. Reading about sports may strike some silly stuff, as time wasted.

“Writing sports, writing a sports column, isn’t easy today. I wouldn’t kid you. It’s tough. From touchdowns and all-star teams and player trades, your thoughts fly to some 350 American boys killed by bombs dropped on barracks at Hickam Field in Honolulu.

Now More Than Ever

“Right now, you can’t keep your thoughts on sports. Nor can the next fellow. And yet, you know better than anything that sports are needed now more than ever before.

“When sports go, that’s when the world is gone.

“You can trace a nation’s trend toward dictatorship by its sports program. The first thing Hitler did after taking over France was to eliminate the sports pages in the newspapers.

Tyranny and democracy are incomparable. Tyranny and sports are incomparable.

Let ’em have it

“What is sports?

“In sports, you just have to play according to the rules. If you can’t do that, out you go.

“Imagine the United States, imagine Cordell Hull, continuing negotiations with Japan while the country’s forces were getting ready to attack, without warning, the Japanese Empire!

“Imagine the United States mercilessly bombing undefended Rotterdam hours after a peace agreement had been reached!

“Yes, you can tag a nation by its idea of sports. The dirty players, the dirty nations, in the end always get the works. May take a long time, but they’ll get it. And the idea now is—Let ’em have it!

The American Athlete

“As the business of letting ’em have it begins, and progresses, and until the end, there’s a greater need than ever for sports.

“Health-giving, body-building, competition-toughening sports.

“Given a choice as to soldier material for defending the shores of this country, give me, above all the American athlete.

New!

“It’s war now. Real war. No more note exchanges and negotiations and more threats.

“And with war, more need than ever for sanity and level-headedness.

“No more moping. No time for pessimism. No time for staleness.

“More reason than ever for doing and thinking the American way.

“Sports is the basis for the American way, the true action of freedom, the true expression of democracy.

“Now, more than ever, is the time for men in sports to do and do better than ever—the work assigned to them.”

Curious about what movies were playing in Nashville on December 7, 1941?

Knickerbocker Theater: “Suspicion,” this Alfred Hitchcock production starred Cary Grant and Joan Fontaine.

Loew’s Theater: “Two-Faced Woman,” with Greta Garbo and Melvin Douglas.

Paramount Theater: “Birth of the Blues,” with Bing Crosby and Mary Martin.

Princess Theater: “The People vs. Dr. Kildare,” with Lionel Barrymore, Lew Ayres and Red Skelton.

Fifth Avenue Theater: “Hold Back the Dawn,” with Charles Boyer, Olivia DeHavelland and Paulette Goddard.

Belmont Theater: “Dive Bomber,” with Errol Flynn and Fred MacMurray.

Belle Meade Theater: “New York Town,” with Mary Martin, Fred MacMurray and Robert Preston.

Searching the Tennessean the next several days, athletics in Nashville did not change, as there were no cancellations of sporting events. High school basketball in the city was underway and continued. Boxing was popular at this time and the December tournaments were held as scheduled at the Hippodrome. The annual Golden Gloves Tournament was held at the Ryman Auditorium in February.

Nashville area high school football all-star selections were announced as were SEC football. Except for the Rose Bowl, all the college bowl games were played as scheduled. The Rose Bowl game was moved from Pasadena, Calif., to Duke University’s stadium in Durham, N.C by request of the U.S. Army. Cleveland Indians’ pitching ace and future Hall of Famer, Bob Feller, announced that he was joining the navy, which he served four years.

George Archie (St. Louis Browns) was the first Nashville professional baseball player to join the army and reported to Camp Forrest in Tullahoma, Tenn. Archie would become Vanderbilt’s baseball coach in 1965-67 to be replaced by Larry Schmittou. The Nashville Vols baseball club was in the news with trade rumors and changes to its roster. Vols’ manager Larry Gilbert was concerned about night baseball being dismissed in the upcoming season due to the war. Night baseball continued in the city.

More Nashville sporting news reported after Pearl Harbor was David Scobey scoring a David Lipscomb then-record for most points in a basketball game (30) against Lindsey-Wilson (Ky). Scobey, a future Nashville Vice-Mayor, would transfer to Vanderbilt and star on the basketball team (1943, 1945). He would become a Commodores’ assistant basketball coach and head baseball coach (1949-51, 1954-56).

As the days and weeks passed, newspaper pages were dominant with war news and photographs while store advertising for the Christmas holidays slowly appeared. Vanderbilt senior football players that announced their intentions to join the military immediately were Joe Atkinson (Marines), All-American Bob Gude (Marines), Mac Peebles (Navy), Dan Walton and George Marlin.

An article in the Tennessean reported on December 14 that “the nation’s college men cannot be exempted from the call to arms merely because of ‘an entirely laudable desire’ to finish their schooling, the United States Circuit Court of Appeals held today. The court with no dissenting opinion, ordered dissolved a temporary injunction issued by the Federal District Court of Montana in the case of Peter Larry Connors, football star at Gonzaga University in Spokane, who sought deferment from call under the Selective Services Act.”

Coach Sanders served in the United States Navy from 1943-45, and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Commander in the navy’s pre-flight training program in Pensacola, Fla. Sanders became the Commodores’ coach in 1940 replacing Ray Morrison. After missing the 1943-45 seasons, Sanders returned to Nashville for three seasons (1946-48) before leaving for UCLA. During the 1943-44 seasons Vanderbilt played a limited football schedule with no SEC opponents.

One of Sanders’ assistant coaches was Paul “Bear” Bryant. Bryant who was Vanderbilt’s offensive line coach for two years was offered at the end of the 1941 season the head coaching position at Arkansas. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the 28-year old joined the U.S. Navy and not the Razorbacks. Part of his enlistment was serving off North Africa and seeing no combat action. Bryant was honorably discharged in 1945.

Vanderbilt played an informal basketball schedule in the 1943-44 and 1944-45 seasons also without SEC competition. In both football and basketball multiple games were scheduled with the military bases located mostly in Tennessee. Vanderbilt did not field a baseball team in 1944-46.

In the December 17 sports edition in the Tennessean, regular sports columnist Raymond Johnson was on vacation and members of the sports staff substituted as guest columnist for his “One Man’s Opinion” column. Guest columnist Will Grimsley wrote: “The Sunday Tennessean reports that Vanderbilt football stars, Jenkins, Rohling, Fritz, Folmar, others, are planning immediate enlistment in the United States armed services. It’s not a shocking news item.

“The rallying of Commodores to the colors at this time of national peril comes as no great surprise to those who know Vanderbilt men. Down through the years it’s always been that way. When the country has called, Vanderbilt men have answered quantities. They’ve needed no shoving.

“World War No. 1 is not so long gone that many of you fail to remember what happened then, and to read a recognizable similarity in the events of today. The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. On May 12 a dozen of Col. Dan McGugin’s finest specimens of athletic manhood were negotiating squads right instead of off-tackles and firing Springfields instead of hog hides.

“Dr. Tom B. Zerfoss, at our request, recalled those days for us yesterday. Dr. Tom was one of the first to enlist.

“‘I remember well. War was declared in April. By May there were something like a dozen of us in the service. There were Russ Cohen, Rabbit Curry, Tom Lipscomb, Tom Ridley, Johnny Floyd, Pryor (Pigiron) Williams to mention a few. We all went in together.

“‘We were all playing baseball at the time. We had played a few games. Well, when we went to camp, the baseball team disbanded. We were stationed at Columbia. Having left school before the term was out, the seniors were allowed to graduate anyhow.’”

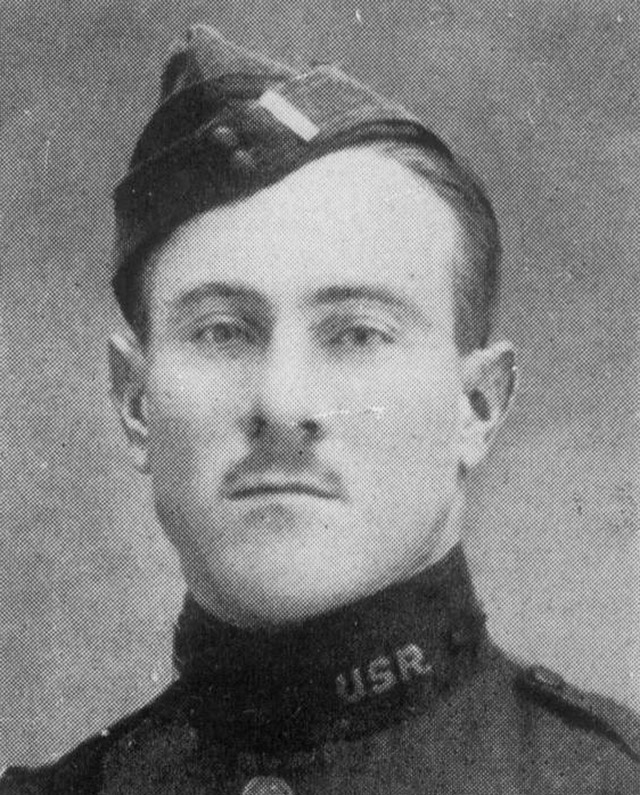

First Lieutenant Irby “Rabbit” Curry in World War I

Grimsley continued:

“For those unfamiliar with Vanderbilt football in the war years, here is exactly what transpired. McGugin took his little, inexperienced squad in 1917 and despite an 83-0 licking at the hands of Georgia Tech (worst in school’s history), managed to beat Transylvania, Kentucky State, Howard, Alabama and Sewanee. The team lost to Tech, Chicago and Auburn.

“The second year, 1918, found both McGugin and Owsley Manier, his side, in the armed forces, too. Ray Morrison was brought up as coach and the team played a limited schedule, losing contests to Camp Greenleaf and Camp Hancock, but beating Kentucky, Tennessee, Auburn and Sewanee.”

The football players mentioned in the column are Jack Jenkins, Jimmy Rohling, Emil Fritz and Jimmy Folmar. Footballers Irby “Rabbit” Curry and Charley Price were both killed in World War I. Head football coach Dan McGugin missed the 1918 season with a short time in the service.

Grimsley began working at the Tennessean in 1932 at age 18. Three years later he became the paper’s sports editor and columnist. He was hired in 1943 by the Associated Press in Memphis then transferred to New York. Grimsley was a sports writer for the AP for 40 years.

In the introduction to the 1942 Commodore, the university’s yearbook, this is written in part:

“The declaration of war by the United States on the Axis found Vanderbilt eager to give full service to the country. Victory in modern war depends on highly specialized knowledge. Skilled technicians hold the balance of power. The army camps can teach the art of war and develop the physical stamina of the men, but the foundation of specialized knowledge must necessarily be laid in the college and university. The emphasis of education at Vanderbilt has been changed, in the College of Arts and Sciences as well as in the professional schools, to point toward the needs of war.

“All through the history of the university, Vanderbilt men have responded quickly to the call to colors. The atmosphere on the campus this time, however, though fully strong and as loyal, has a somewhat different form of expression. During the first World War, a student was considered unpatriotic, and life with his fellow students was hard if he had not volunteered for active duty or was not studying some profession directly connected with the pursuance of war. In the spring of 1917 baseball and track gave way to military drilling. The boys were organized into four companies and were drilled by trained officers.

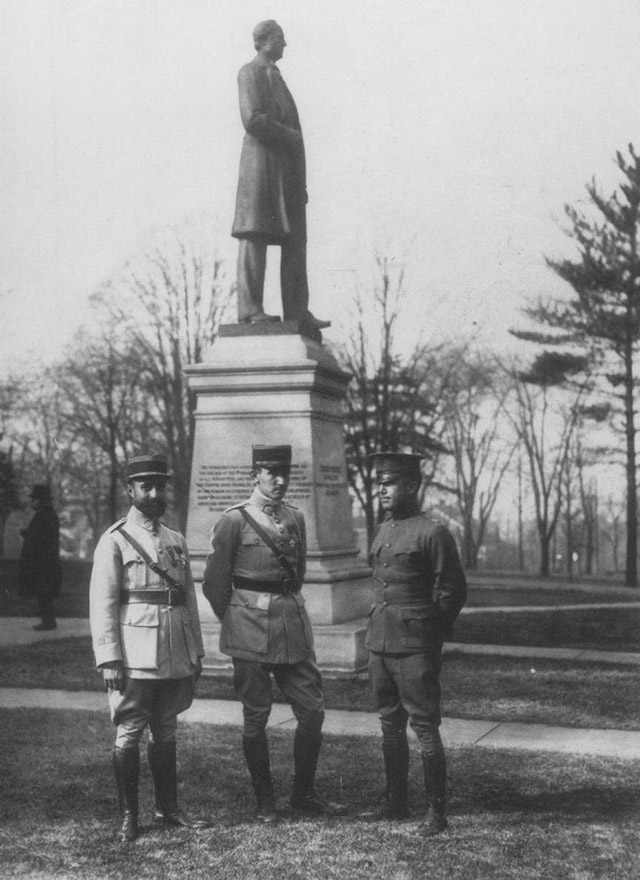

French army officers visit the Vanderbilt campus during World War I.

“On November 16, 1917, doctors and nurses in the Vanderbilt Hospital Unit left for active service amid the ovation of a huge crowd in the Ryman Auditorium. In the fall of 1918 Vanderbilt University became an armed camp. It was detailed by the United States Army as a unit of the Student Army Training Corps. Nearly 500 men were listed in the unit. Kissam and Wesley Hall were turn into barracks, there was a canteen and the gymnasium served as the ‘Y’ room. All courses of study were subordinated to the military training, and activities were at a minimum.

“The nature of the present war, however, has changed the type of service demanded of university men and of the university itself. The only semblance of the armed camp on the campus this year is the drilling of the company of students enlisted in the Tennessee State Guard. Before our entry into the war this time the government was able to establish a system of training camps which eliminates the necessity of turning college campuses into drill grounds. The theory of the Selective Service Act has wrought the greatest change. This assumes that every man is willing and ready to serve his country.

“The government calls men as they are needed. The theory is that each individual can best serve his country in the particular niche into which he fits best. University training is as important as military training in the business of scientific destruction. Students are discouraged from enlisting. They are urged to continue their education as long as possible in order to prepare themselves for any task their country asks of them. Vanderbilt students are as eager and ready to serve their country as they ever were. They are calmly waiting for their call to duty.”

In 1940, medical schools across the country organized reserve units in the event the United States entered a second world war. On July 16, 1942, the Vanderbilt University 300th Medical Hospital Unit departed Nashville for Camp Forrest for training. On November 10, 1943, the unit set sail for Naples where it established a 2,000-bed hospital to treat soldiers from the battlefields in Italy. The hospital treated over 37, 000 patients until July 1945.

Vanderbilt’s basketball team in 1941-42 finished the season 7-9 (SEC 3-8) and played its normal schedule. Several years later Vanderbilt constructed a new gymnasium that was ready for its first home game in December 1952. Memorial Gymnasium is named in honor of the 144 former students, men and women who lost their lives in World War II.

Traughber’s Tidbit: Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, the great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt for which Vanderbilt University is named, died on the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. The Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat off the coast of County Cork, Ireland. The sinking of the Lusitania was one of the reasons for the United States entering World War I. Vanderbilt was seen helping fellow passengers into lifeboats and gave his life jacket to a female passenger saving her life. The ship sank in 18 minutes. Vanderbilt was traveling first class with his valet and neither body was recovered.

His son, William Henry Vanderbilt III, dropped out of prep school shortly before the United States declared war on Germany and was appointed as a midshipman in the U.S. Naval Coast Guard Defense Reserve. Vanderbilt was only 15 years old and one of the youngest Americans to serve in the war. Later he served one term as the Governor of Rhode Island (Jan. 1939-Jan. 1941) and as a Naval Reservist was assigned to the Panama Canal Zone during the first part of War World II. He later served on Admiral Chester W. Nimitz staff in Pearl Harbor as a lieutenant commander, commander and captain. Other members of the Vanderbilt family also served in World War II.

Tidbit Two: Vanderbilt All-American quarterback, Irby “Rabbit” Curry (1913-16) was killed in aerial combat on August 10, 1918, near Chateau Thierry on the River Marne in France. This is an eyewitness account to Lieutenant Curry’s death: “Irby and a classmate from Vanderbilt were in the same aero squadron. At Chateau Thierry their squad engaged the Richthoffen’s circus (Germany’s greatest aero squad). Irby was wounded and went into a tight spiral to land. He never gained strength enough to come out of the spiral and crashed to the earth. His classmate downed a plane and landed to get the German, but landed on German soil and was captured. Nine out of eighteen of Irby’s squad were killed.”

When the new Vanderbilt football stadium was built in 1922, Dudley Field was dedicated. The original Dudley Field was renamed Curry Field in honor of “Rabbit” Curry. Curry Field was used for baseball and track and is on the present campus location of the Vanderbilt School of Law.

If you have any comments or suggestions contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.