Jan. 2, 2008

|

|

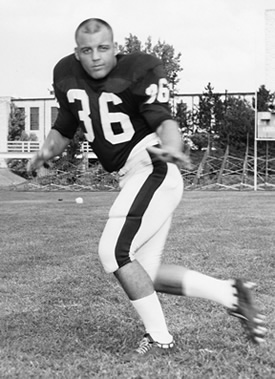

| Current Vanderbilt economics professor John Vrooman during his Kansas State football days. |

Subscribe to Commodore Nation magazine / View Archived Issues

We’ve all had professors from different backgrounds with different degrees from colleges all over the country. Maybe a professor used to be in the band or was involved with student government, but did it ever cross your mind that your professor was a former Division I athlete? Perhaps you should have taken a closer look. From tennis players to football players, Vanderbilt’s faculty is dotted with former Division I athletes who are taking what they learned in athletics and transferring it into the classroom.

Although they played different sports in different eras, each professor has shared similar experiences in athletics that have helped shape who they are in the classroom.

Since playing tennis at Pittsburgh in the late ’80s, political science professor Marc Hetherington sees how competing in college athletics has benefited him both in and out of the classroom.

“Playing sports was a really important thing for me to do, and it gave me perspective on life that probably comes out in ways I have no idea,” Hetherington said.

Vanderbilt law professor and former UMASS lacrosse player Paige Marta Skiba agrees with Hetherington.

“I played sports all through middle school, high school and college,” Skiba said. “Playing sports just takes so much discipline, so I think that kind of discipline is what led me to being successful.”

Economics professor John Vrooman believes that his experiences as a football and baseball player at Kansas State have taught him how to be an even better teacher.

“Sports gives me a notion of confidence and of understanding in the classroom,” said Vrooman, who is regarded as one of the top sports economists in the country. “(Lecturing) kind of relates to when I was at K-State, and I was the guy that gave the pre-game pep talk and halftime pep talk. I was always a pretty emotional guy and kind of talked from the heart a lot. I do that same thing in my teaching, which is why I became a pretty effective public speaker, particularly with large groups.”

A former safety on the gridiron, Vrooman also made his mark in the return game, where his punt return average of 12.7 in 1965 still ranks ninth in school history.

“A lot of people think, how can you (lecture to) 600 people, and I say, `Well I returned punts in front of 80,000 people in Lincoln, Neb., I imagine I can talk to 600 kids,'” Vrooman said. “(Lecturing) is the same sort of rush you have when you are alone as a punt returner because you are out there all alone. That experience makes me a better teacher.”

Similar to Vrooman, Mark Schoenfield, an English professor and former wrestler at Yale, believes that his experience on the mat has helped him get information across to students.

“I’m not a great athlete and never was, but wrestling is one of those things that you can use whatever you have, whether it be smarts, strength or speed to make the most of and maximize your advantages,” Schoenfield said. “I think the way that translates into teaching is that all students have learning capabilities, but those capabilities are different. You try to develop a classroom where their strengths flourish, but you don’t always get it right. That is something that if not for wrestling, I’m not sure I would have caught on to.”

The life lessons that are learned through playing athletics also have found a meaningful place in the classroom. One example of this is through the teachings of sociology professor and former Vanderbilt football player Rosevelt Noble. Noble has brought the competitiveness he learned on the football field and transferred it to his students in the classroom.

“I’m very competitive and so sometimes, subconsciously, I’ll set my students up in a competitive environment,” Noble said. “Sometimes competition can bring out the best in you. Periodically, I give them their ranking in the classroom, and there are some students that become obsessed with improving their ranking. If realizing where you are makes you want to study more and study harder, then my mission is accomplished.”

While a competitive environment helps to spur interest in a classroom for Noble, some professors, including Vrooman, try to relate some of the subject matter through analogies relating to sports.

“I relate (economics) to sports all the time,” Vrooman said. “One analogy I use is of a quarterback or point guard. You just don’t run a play blindly, you take a look and see what the defense is offering you and you see what the reality is. The secret to economics and public policy is don’t make up your mind up about what you are going to do until you see what the reality is.”

With a multitude of philosophies that go into determining exactly what the best way is to lead a classroom, professors have taken a view that is similar to that of a coach on the sideline.

The knowledge of working with different coaches and seeing different leadership techniques work and not work for certain teams and personalities has given professors with athletic experience a unique perspective into managing a classroom of students.

Orthopaedic trauma professor and former Duke football player Bill Obremskey constantly uses coaching techniques when dealing with patients.

“Part of our education is not just in the learners or residents, but a lot of it is in patient education and that is a little bit more like a coach, where you are trying to teach them what you want them to do,” Obremskey said. “There are different coaching styles of either scaring (the patient) or trying to make them part of the process. I try to take the attitude of making them part of the process and stating that it is their responsibility for their recovery of their injury and to make them a team member instead of just giving instructions.”

Hetherington also believes that the way a professor works in the classroom is very similar to that of being a coach in athletics.

“By being a teacher, in a sense, you do become a coach, and it’s the role you take on in the classroom,” Hetherington said. “The kids in your classroom are your team, and your job is to try to get as much out of them as you can.”

Similar to Obremskey and Hetherington, Schoenfield views his role in the classroom through the eyes of how a coach views a team.

“I really just think of my role when I teach as a coach more than an evaluator or a referee,” Schoenfield said. “Another thing I realized is that I always did better at home when the crowd was on my side, when I really felt my teammates were behind me, and I realized that really worked very well in the classroom when students support each other.”

Having seen both sides of being a student-athlete and now working in academia, professors who played college sports also know the challenges and constraints that go into balancing school with athletics.

“With sports, you learn how to totally throw yourself into something for two hours and then how to take a 15-minute transition to get to something else,” Schoenfield said.

A member of the National Football Foundation Academic All-America Team as a senior and a three-time Academic All-ACC selection at safety, Obremskey saw immediately the improvement in his time-management skills at the conclusion of his playing career.

“It was probably the most challenging part of my entire educational process,” Obremskey said. “Nothing else took the same complete commitment and dedication and hours that playing football, going to school full-time and trying to be successful in school to go to medical school took.

“You had a 40-hour-per-week job playing football and at the same time trying to go to school fulltime with people who are really smart,” Obremskey said. “After football was over, medical school wasn’t so bad because suddenly you had 10 hours to do six hours of homework instead of three hours to do six hours of homework. Athletics absolutely helped my time management.”

Coupled with the enhancement in time-management skills, Skiba believes that the drive it takes to become a Division I student-athlete on the field also translates well into a student-athlete’s drive in the classroom.

“I always think that athletes are the best students because of the drive they have,” Skiba said. “You just don’t become a Division I athlete without being extremely competitive and staying focused and driven. A lot of times student-athletes get a bad rap because people think that student-athletes are not really students, but I’ve always found that athletes are the best students.”

That knowledge of what it takes to become a student-athlete and compete at the Division I level also brings a special bond between professors and current student-athletes.

“Athletes kind of migrate to you because they know you are one of them,” Vrooman said. “There is sort of a fraternity that runs under all of this, and it goes back to the fact that we have led a very complicated college life and they know the pressures that are on their time. There is that kind of hidden respect.”

Obremskey sees a similar bond in the medical field with his medical students that are former athletes.

“I think there is that admiration there,” Obremskey said. “Somebody who has had the commitment themselves to the same type of things that you have, you know that they have a high gear. If they have been able to succeed academically in the medical field and at the same time compete at a very high level of athletics, to do both they have a reserve of something.”

The admiration for professors who competed in college athletics doesn’t end just with current student-athletes. Students in general seem to find a special bond with professors through sports.

“In the classroom, sports are very much a part of the way I try to warm to the students,” Hetherington said. “I’ve been fortunate over the course of my 10 years of teaching to win awards, and I think it is because my students can relate to me. I definitely use sports a lot. The way I talk about athletics is to kind of humanize me. I think the students are able to see me as a human being through sports.”