Aug. 29, 2007

CHC- Watson Brown (pdf) | CHC Archive

This interview with Watson Brown is exclusive to VUCommodores.com and Commodore History Corner.

|

|

Watson Brown, former Vanderbilt football player and head coach, knew what a football was just hours after he was born. While laying in his Cookeville General Hospital crib on his April 19, 1950 birthday, Brown’s grandfather placed a toy football by the infant’s side.

The proud grandpa was Eddie “Jelly” Watson. Jelly Watson earned 16 letters playing four sports at Tennessee Tech and spent more than 30 years as a high school coach and teacher. He posted a 118-31 record during his final 15 seasons as head football coach at Cookeville Central High.

“I hung around him a lot at a young age while he was coaching at the high school,” Brown said recently from his Tennessee Tech office. “We went on trips, stayed on the sidelines and were in the same town a lot with my granddad. My mom, dad and grandparents were a major influence on Mack [Watson’s younger brother] and me as far as athletics.”

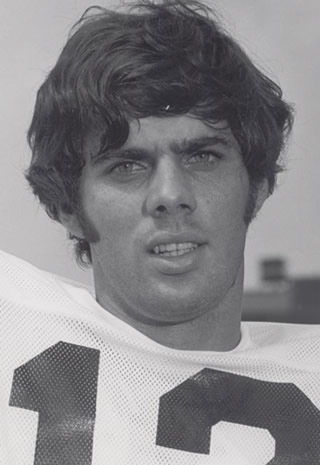

Brown, 57, was All-State, Mid-State MVP and a prep high school All-American quarterback who led Cookeville to a 10-0 mark during his senior season. His options were plentiful as dozens of colleges were interested in his talents. Brown also had offers from professional baseball. While recruiting Brown, Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant said he would be the next Alabama All-American quarterback. But Brown chose to play for coach Bill Pace at Vanderbilt.

“In those days you could visit as many times as you wanted,” said Brown. “I went down there six times to visit at Alabama. That’s where I was going. I told him I was coming there and at the end I backed out and went to Vanderbilt.

“I thought at the end we could get it turned around at Vanderbilt and I wanted be a part of that. I look back on myself and think I’ve always been an underdog. Take chances and try and take a hold of something that hasn’t worked or people say can’t work or whatever. I guess now I can look back and say that. I felt Coach Pace could get it done.”

Brown led the Commodore freshman football team to a 5-0 record. His most productive year came as a sophomore before injuries limited his college football career. Brown did start a few games at quarterback in his first year of eligibility and returned punts and kickoffs. His first game in 1969 was against Michigan at Dudley Field.

“The first time I started was returning punts and kicks against Michigan,” Brown said. “I remember I was so nervous I let the opening kickoff hit the ground. We all went falling for it and one of my teammates recovered it. I got off to a great start. I had a good year as a sophomore and really good start as a junior. But I got injured and really didn’t play much again.”

Brown is best remembered as a player for engineering the winning touchdown drive in 1969 against 13th ranked Alabama in Nashville. He was the starting quarterback, but split time with Denny Painter in the game. Brown came off the bench late in the fourth quarter with a first down on the Tide’s 21-yard line.

Brown handed off to running back Doug Mathews for 11 yards and Daniel Upperman was stopped at the line for no gain. On third down, Brown threw a strike to tight end Jim Cunningham for the winning TD. Vanderbilt held on the last two minutes to secure the 14-10 victory. Pandemonium broke out as fans rushed the field. This was the last game Vanderbilt has won at home against Alabama. Brown was 11-of-15 passing for 119 yards while rushing 22 times for a game-high 68 yards.

“Coach Bryant, before the game, walked by me and was cutting up with me,” said Brown. “He said, `You couldn’t throw when I recruited you and you can’t throw now and you’ll never be able to throw.’ He just kept walking and patted me on the head. Then after we won the game, he found me in all the melee and it was melee. He gave me a hug and didn’t say anything and strolled to the locker room.

“When I couldn’t play anymore and decided I wanted to coach, Coach Bryant really got me started and I called him for advice on every job I was offered until the day he died. He kind of took me under his wing and said, `I’ll help you go here, maybe don’t go here.’ It was neat that I didn’t play for him, but he took care of me until he passed away.”

In an injury-plagued career, Brown’s career statistics include 171 rushes for 369 yards (2.2 avg.) and 10 touchdowns. As a passer he completed 113-for-206 (54.9%) for 1,242 yards and seven TD’s. Brown also fielded six varsity punts for 85 yards (14.2 avg.) and one touchdown.

Brown missed his entire junior season in 1971 due to his injuries. Pace would be fired the next year after six seasons. His overall record at Vanderbilt was 22-38-3. Brown was asked if he might have had any regrets on not accepting a scholarship from Bryant.

“I loved being at Vanderbilt,” said Brown. “I got my degree there and a lot of good things have happened since then. Do I regret not going to Alabama or looking back? Do you think about it? Yes.

“I could have gone ahead and played professional baseball and gone through the ranks of that. But I didn’t do that. You always look back and wonder. I’m very proud to have been a Commodore and wished that I could have played more than just my sophomore year. I really wished I could have stayed healthy to see what could have happened to us.”

Steve Sloan took over the coaching duties at Vanderbilt and Brown became his graduate assistant coach. In the following years Brown was an assistant coach at East Carolina (1974-75) with head coach Pat Dye, Jacksonville (Ala.) State (1976-77) and for Rex Dockery at Texas Tech (1978). While at Jacksonville State, in his role as offensive coordinator, Brown was named Gulf South Conference Assistant Coach-of-the-Year in 1977.

“There are philosophies that I have gotten from everybody I’ve been with,” Brown said. “There are things I got from Steve [Sloan]. Coach Dye, who was such a Coach Bryant disciple, I probably took more of his philosophy on things more than any coach that I worked with or for. That’s the neat thing about this business. Everything you do, you basically get from somebody else and you put it together the way you want to put it together. There are not a lot of inventions in this business.”

In 1979, Brown reached a goal of being a head coach with his hiring at Austin Peay State in Clarksville, Tenn. At age 29, Brown guided the Governors to consecutive 7-4 records and each year was runner-up in the Ohio Valley Coach-of-the-Year balloting.

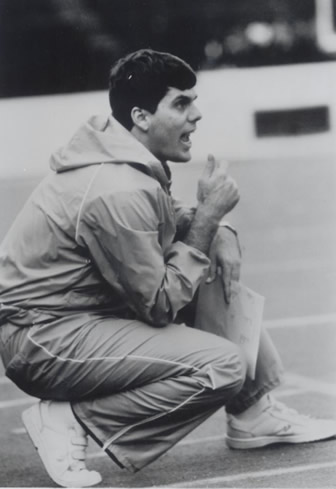

Vanderbilt head coach George MacIntyre would call Brown back to the Vanderbilt campus in the role of offensive coordinator. In those two seasons, Brown’s Commodore’s offense would set dozens of offensive records with a wide-open multiple offense. The 1982 Dores were 8-4 with a Hall of Fame Bowl loss to Air Force, 28-20. This was Vanderbilt’s last bowl appearance. MacIntyre gave Brown full control of the offense.

“When I came from Austin Peay, he said here go with it,” said Brown. “Coach MacIntyre was a great guy to work for. We had three of four really good football players like Whit Taylor, Norman Jordan and Allama Matthews. We had some winners that were playmakers, smart kids.

“You can go further with those kinds of kids. We were really wide-open, kind of complex and complicated for those times. People weren’t throwing the ball at all then. Those kids could handle just about anything I’d throw on them.”

Vanderbilt passed for 3,036 yards and 19 touchdowns in 1981 to rank 8th nationally and No.1 in the SEC. In 1982, the Commodores passed for 2,837 yards and 26 TD’s to repeat as the top passing team in the SEC and 13th in the nation.

After two seasons at Vanderbilt, Brown was hired as head coach at the University of Cincinnati. Brown made an instant impact in the season-opener with his Bearcats. National attention was gained with a 14-3 upset victory over Penn State in Beaver Stadium. The Nittany Lions were defending national champions at the time.

“The city went crazy,” said Brown. “We had a sellout for our first home game the next week when we played Oklahoma State. Penn State had won the national championship the year before. I think the Cincinnati team that had gone there the year before got beat 50-something to nothing, a real bad score. It was just one of those days that we just couldn’t do anything wrong. It was a great, great day for the University of Cincinnati.”

Brown was 4-6-1 in his lone season in Cincinnati. His next stop was at Rice University to become head coach and athletics director. Brown said he left Ohio not for the money as people thought, but to fill his family’s wishes to return to the South.

In his two seasons (1984-85) at Rice, Brown accumulated records of 1-10 and 3-8 for the Southwest Conference member. MacIntyre was relived of his coaching duties at Vanderbilt after seven seasons and a record of 25-52-1. Vanderbilt Athletics Director Roy Kramer looked to Houston for the next Commodore coach.

“I was immediately contacted and offered the job,” said Brown. “I didn’t feel good about it to be very honest. I didn’t think it was the best time to go back. And I just nearly backed out. If it hadn’t been Coach Kramer, I believed I might have stayed at Rice. It’s your alma mater and it’s hard to say no.

“As Brenda my wife has said to me many times, `You were going to go back sometime. You were going to take it at some point because it was your school.’ It’s really the only job I took that I really didn’t feel good about. I knew there was so much to do there. But once you go, you go. It’s my school. I did the best I could while I was there.”

Vanderbilt did not have much success on the football field in many years. Since 1953, the previous six coaches at that time had secured losing records except for Sloan (12-9-2). Brown knew about the program’s deficiencies, which was a concern.

“Coach Kramer built what they have now,” Brown said. “They had a major steroid incident that was hanging over the program. There were not very many scholarships. They were full up on scholarships. We could not sign very many players the first two years number-wise when I was there.

|

|

“The things you look for as a coach, when you try and rebuild a program, was not there. I took a major cut in pay to go back. That was another thing I had to deal with. I was concerned about being in two tough jobs in a row at Rice where they had lost so many games in a row. When the Vanderbilt job came, I knew it was going to be tough with back-to-back schools in a row. That’s hard to deal with in that profession. You get about two days to make up your mind.”

In two years Brown was forced to face his brother Mack who was the head coach at the time for Tulane. Mack won both contests. Brown said that it was a problem playing against his close brother since they had never been against each other in anything.

Mack, who is one year younger than Watson, actually followed Watson to Vanderbilt as a football player. When Watson was hurt and it was apparent his football career would be limited, Mack left Vanderbilt. He saw little action in one season and transferred to Florida State. There were a few times the brothers faced each other while Watson was an assistant and Mack a head coach.

In Brown’s five seasons (1986-90) at Vanderbilt, he managed a 10-45 (SEC, 4-29) record including three 1-10 tallies. His biggest win was against Florida in 1988 when the Commodores stunned 20th ranked Florida, 24-9. In Brown’s final season his Commodores defeated LSU in another upset in Nashville.

The opening game in 1990 would turn out to be a low point in Brown’s effort to rebuild Vanderbilt’s football program. SMU was coming off a two-year death penalty imposed by the NCAA for recruiting violations while on probation. Vanderbilt was embarrassed, 44-7 in Dallas.

“Any loss is a low point,” said Brown. “We were a real young team and we were better than SMU, but they were more experienced and older than us. You go back and looked at who played for us in that game. Those kids went on in the next couple of years to make Vanderbilt more competitive.

“Right at the end we were really fixing to have a good football team. I knew it was going to take longer there than it would any other place. I thought we wee looking at six or seven years before we could have it going. We had to do so much. We had to change the image and the SEC was rolling at that point it was really tough at those times. It was a tough time to be in the SEC and I knew what I was walking into.

“We played so many close games. I would hate to go back and see how many less than a touchdown losses we had. I know that we were in the lead going into the fourth quarter many times just not good enough or deep enough to hold on at that point. I really would have loved to have a couple more years and I believed we would have had it turned around. It was the decision that I made and never regretted it in any way.”

After the SMU game, rumors were circulating that Brown’s job was in jeopardy. Brown said that those rumors did not reach him and he did not feel any pressure. He thought the press was good to him and understood his situation in rebuilding the program. But he was surprised by the way his time at Vanderbilt ended.

Before the final Tennessee game, Brown met with Vanderbilt Chancellor Joe B. Wyatt and athletics director Paul Hoolahan. Brown left that meeting realizing he was in trouble. After a loss to the Vols in Dudley Field, it was announced that Brown was reassigned to the alumni development office. Brown’s contract was later settled and he left Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt fans were in an uproar in the way Brown’s departure was handled. Brown was very popular with the Commodore fans and in the Nashville community. A few days after the UT game, Gerry DiNardo was named as the new Vanderbilt coach. John Bibb of The Tennessean reported that DiNardo had been in town one day during the week of the Vols game to discuss the Vanderbilt coaching job. Brown did not want to talk about the events concerning those controversial final days.”

“The tough thing for Vanderbilt is they’ve had much better teams than their records,” Brown said. “That’s because they are in the best league in the country–top to bottom. It’s the toughest league in the country. When you beat an SEC team, you’ve played well. You have to stay healthy. But again times are different.

“Bobby [Johnson] has it going and has the best shot to get it going. It’s a good time for them and I’m 100 percent behind him. I will help in any way that I can to do that. It’s not easy. It never has been. But it’s not because Vanderbilt doesn’t try. In those early years it was the competition and who you were playing.”

Brown would coach for Jackie Sherrill at Mississippi State (1991-92) and Gary Gibbs at Oklahoma (1993-94) before beginning a 12-year tenure at UAB. The Blazers began playing football in 1991 as an Independent in NCAA Division III. When Brown joined the team in 1995 they were in Division I-AA, but moved up to Division I-A and joined Conference USA.

“We started that one from scratch,” Brown said. “I loved it. I’d never taken a program where you just start from scratch. Your ordering new shoulder pads and helmets the whole thing. They were just starting. They just had a few scholarships. That was different from any that I’ve taken over before. You look at where I’ve been. I seem to go find the toughest ones there are, and take them.”

During Brown’s first three seasons the Blazers were a very respectful 5-6. It was in his second season he faced an SEC foe–Vanderbilt. The game was played in Nashville and the Commodores won the hard-fought contest, 31-15. It was not a homecoming for Brown.

“That was hard,” said Brown. “We weren’t very good. It was our first year in Division I-A, but we were competitive that whole year. I would love to have brought in one of my teams from the past four or five years. Just coming back was hard and I knew after that time, I didn’t want to do it again. It brought back too many memories in too many ways.”

While at UAB, Brown was later in the dual role of athletics director and head coach. Brown did an amazing job in upgrading the facilities and building the program into a conference championship contender. The other sports at UAB were also improved during Brown’s time at the school.

In 2000, the Blazers went to Baton Rouge and shocked LSU, 13-10. UAB has been bowl eligible three times and earned a trip to the school’s first and only bowl game in the 2004 Hawaii Bowl. The Rainbows won, 59-40. Brown’s overall record at UAB was 62-74 while his overall career record is 94-151-1.

In December of 2006, Brown was named the new head coach at Tennessee Tech. Brown returned to his hometown of Cookeville and became the Golden Eagles 10th head football coach. He was asked if going home was destiny.

“It came at a time in my life where I’m 57 years old and I’ve been doing this for 35 years,” said Brown. “It’s a little bit of the same reason I went to Vanderbilt. I wanted to come back and give something to my community. My best friend’s daddy was the head coach at Tennessee Tech. The stadium is named after him. His daddy and my daddy were roommates in college. So the families have been so close.

“Tech has great tradition here and hasn’t had an OVC championship in 30 years. So here I go again. I really want to this to be my last go around. This will be it for me. I want to leave a mark here at Tennessee Tech and leave this program really strong. I want to bring back a championship or two before I go play golf, get into a ski boat or fishing boat and have a good time.”

Brown contributions to athletics have not gone unnoticed. He was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame in 2003 and was recently inducted into the first Cookeville High School Hall of Fame. Other partial inductees into the inaugural HOF were his grandfather “Jelly” Watson and brother Mack. Mack has been a longtime college coach and will be entering his 10th season at Texas. His Longhorns won the national championship in 2005 with quarterback Vince Young.

Brown’s daughter, Ginny, was a four-year letter winner in basketball at Georgia State University (1996-2000) and son Steven played football at UAB for his father. Also living in Cookeville is Brown’s brother Mel and mother Katherine.

Looking back, would Brown do anything differently concerning his career?

“You always look back and say what if I’d done this,” Brown said. “What if I’d not gone to Cincinnati? What if I’d gone to Alabama as offensive coordinator when Ray Perkins offered me that? What if I’d gone the baseball route that I very well could have done? Life has been great for me. What would have happened if I hadn’t gotten hurt?

“I’ve had a wife for 35 years, two great children and been healthy except for my physical deal with my arms and leg from the injuries from football. It’s been a wonderful life and I don’t think you can go back.

“One thing I can say that every place I have coached, we tried to do what was best for that school and I always wanted the kids to be No.1. And try to take care of them the best I can and teach them the right things. I know I’ve done that wherever I’ve been. That’s what will really matter when it’s all said and done and it’s really over.”

While Watson Brown has a connection to Vanderbilt athletics with highs and lows, he remains one of the most popular figures with Commodore fans and in the Nashville community.

Said Brown, “Make sure that the Vanderbilt fans know there is still Vanderbilt blood right there down deep, and there always will be.”

If you have comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via e-mail WLTraughber@aol.com.