Nov. 7, 2007

![]() Hinkle: Iron Man All-American | History Corner Archive

Hinkle: Iron Man All-American | History Corner Archive

|

|

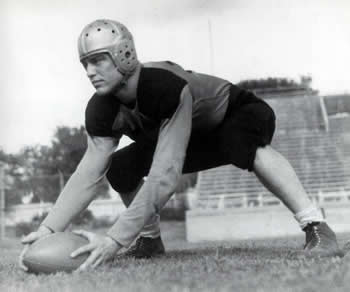

Carl Hinkle (1935-37) displayed his iron man toughness during his senior season while playing all 60 minutes in seven games as a lineman.

“Determination,” Willie Geny (1933-34) a former Vandy player and Hinkle coach said at the time of Hinkle’s death in 1992. “That was Carl Hinkle. He wanted to be the best and he was the best. I remember he knocked three or four men out of that game (1937 Tennessee). On one play, he hit Tennessee’s George Cafego and I remember Hinkle saying, `He’s through. Take him off.'”

Hinkle was born in Hendersonville, Tenn., and attended Hickman County High School before graduating from Franklin’s Battle Ground Academy. He was a dominant player in the line while playing as a sophomore and junior. But, it was his outstanding play as a senior in 1937 that gained Hinkle a national reputation as one of the country’s best football players. Hinkle was also the Vanderbilt team captain.

The Commodores, led by Coach Ray Morrison, entered the 1937 Tennessee game, 6-1 on an autumn afternoon in Knoxville. Their lone loss at that point in the schedule was with Georgia Tech. Coach Robert Neyland’s Vols entered the game, 4-2-1. Vanderbilt won the contest, 13-7 with two touchdowns and a missed extra point. A newspaper account of the game from the book Fifty Years of Vanderbilt Football by Fred Russell and Maxwell E. Benson read:

But for the gallant Carl Hinkle, Tennessee would have scored, perhaps won. This super-performer single-handedly clinched the victory for Vanderbilt. With only five minutes to play, a pass from Cafego to Eldred had set the ball on Vanderbilt’s nine. Cafego was running wild, splitting the middle and circling the ends. It seemed impossible to head them.

On second down, he tore through center, where Hinkle met him with a murderous tackle that sent him from the game, groggy and reeling, just as the Commodore’s captain had put out Cheek Duncan with a bone-rattling blast three plays before. Their exit took somewhat out of the Vols.

Later the brilliant Hinkle intercepted Babe Wood’s pass and lugged the ball to midfield. Morrison rushed in Pluckett and he killed the remaining seconds with three wide, sweeping end runs. It was the first victory over Major Neyland since 1926. Vanderbilt made only one line substitution, Henderson for Merlin.

The last game of 1937 was against undefeated Alabama (8-0) on Vanderbilt’s Dudley Field on Thanksgiving Day. Though it was not known at the time, the winner of this SEC battle would be invited to the Rose Bowl to play California. Frank Thomas was the head coach for the Tide. Hinkle would be part of one of Vanderbilt’s and the SEC’s most historic plays.

Vanderbilt had the ball on its own 41-yard line with one minute left until the first half with the score tied, 0-0. Quarterback Bert Marshall gained four yards followed by a trick play. The Commodores tried to repeat the famous “hidden ball” play that beat LSU earlier in the season. In that game, Commodore tackle Greer Ricketson picked up the ball left on the ground to sweep around end for a 50-yard touchdown.

Alabama must have been looking for the play as they quickly recovered the exposed ball. The ball was marked on the Vanderbilt 44-yard line and four plays later Bama scored on a touchdown pass before the half. The extra point was missed as the Commodores trailed at halftime, 6-0.

Vanderbilt came out in the third quarter fired up as the Commodore fans were roaring in the stands. Marshall would direct a 53-yard touchdown drive with fullback Hardy Housman finding the goal line for a touchdown. The extra point was good and Vanderbilt led, 7-6.

With six minutes left in the final period, the Tide lined up for a 23-yard field goal attempt by a substitute end named Sandy Sanford. Sanford was facing a tough angle, but the kick was good. Hinkle charged the ball, but just missed the block by inches. The Commodores could not move the ball for a score in the final minutes and Hinkle walked off the field in his last game with a disappointing defeat. Alabama won 9-7, but lost to California in the Rose Bowl, 13-0.

Hinkle would talk about his thoughts on his final moments in the last college game of his career. Russell relayed Hinkle’s recollections in one of his Banner columns:

“I was groggy going off the field, a little sick at my stomach. The between-halves rest helped. No complaints from the coaches; just a few instructions. We went back out really `ready’ and had that touchdown pretty quick. They couldn’t stop Bert Marshall. When Joe Agee made the extra point, I was sure we had `em. It was a great feeling.

“Then they started a terrific drive. We were tiring, but I thought we could hold on. When they got to out to fourteen, fourth down, and Sanford came in, I guessed wrong again, thinking it might be a fake. Rushed him all I could, though. A field goal through the middle, and we were behind again. But until the very last play I still thought we might get `em, that Marshall might get loose. Then it was over.

“I reached down and got the ball. I knew I couldn’t keep it. They deserved it. I handed it to Kilgrow. As I walked to the field house, I realized my playing days were over. I had to laugh a bit. I wasn’t ashamed to lose. It had to be someone–why not us? Amazingly, I felt all right. It wasn’t painful. I didn’t cry. I wished we were starting over.”

Joe Kilgrow was Alabama’s All-American halfback that finished fifth in the Heisman Trophy voting that season. Hinkle was seventh in the voting. The year, 1937, was the third year the award was in existence. Running back Clint Frank of Yale was the 1937 recipient of the Heisman Trophy.

Hinkle won the 1937 SEC Most Valuable Player Award (just the sixth Vandy player to receive the honor) and a First Team All-American selection by the Associated Press, Grantland Rice and Liberty. He was enshrined into the National College Football Hall of Fame in 1959.

After graduation, Hinkle turned down several offers to coach and play professional football. Hinkle did accept an appointment to West Point though he was ineligible to play football. However, Hinkle did scrimmage with the Cadets. At West Point, Hinkle received the top military honor by being named Regimental Commander (First Captain). The honor also presented Hinkle with the General John Pershing Sword.

During World War II, Hinkle served as a pilot and won the Distinguished Flying Cross with two Oak Leaf Clusters, Presidential Citation Unit with Oak Leaf Clusters, France’s Croix de Guerre, the Air Force Medal of Commendation. Hinkle would retire from the Air Force as a colonel.

Hinkle was named to the Vanderbilt Hall of Fame in 1969 and the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame in 1970. He died of a heart attack in 1992 at age 75 in Little Rock, Ark. Hinkle was buried with full military honors in the National Cemetery of Little Rock.

If you have comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via e-mail WLTraughber@aol.com.