Sept. 28, 2011

Commodore History Corner Archive

Editor’s Note: Nashville sports historian Bill Traughber has enlightened Vanderbilt fans over the years with his thoughtful essays on Commodore history. The award-winning author has recently written another book, Vanderbilt Football: Tales of Commodore Gridiron History. The 160-page paperback book includes 55 photos and can be ordered on historypress.net for $19.99.

A definition for a nickname can be a name considered desirable, symbolizing a form of acceptance, but can often be a form of ridicule. They can be awarded to, not chosen by the recipient. It can be based on a person’s name or various attributes.

A definition for a nickname can be a name considered desirable, symbolizing a form of acceptance, but can often be a form of ridicule. They can be awarded to, not chosen by the recipient. It can be based on a person’s name or various attributes.

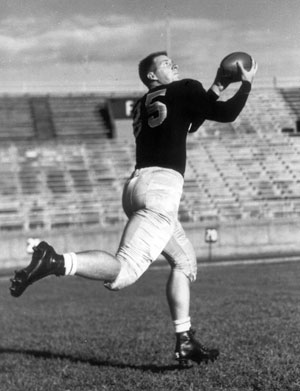

But for former Vanderbilt football player Ernest Jackson “Bucky” Curtis (1947-50) that was not the situation.

“When I was a youngster, I asked for it as a nickname because there was a football player at Notre Dame named Bucky O’Connor,” Curtis said recently from his Louisville home. “He played for the Irish in the mid-1940s and was kind of my hero. And I never outgrew the nickname.”

Curtis, 82, is from Gainesville, Ga., and was recruited by Georgia, Georgia Tech, Vanderbilt and a few smaller colleges. His father was a high school football coach and athletic director, but Vanderbilt had an advantage in recruiting the talented Curtis.

“The head coach at Vanderbilt [Red Sanders] got his first coaching job with my dad. My dad was with the Riverside Military Academy in Gainesville, Ga. He hired Red. Red never married and didn’t have any children so he kind of adopted me. I got my first baseball glove and my first football from Red. So when I was being recruited, I told him I was interested in Georgia Tech. Red said, `You’re not going anywhere, but Vanderbilt.’

“I had a sister at Vanderbilt. When I was being recruited I went to Nashville when Vanderbilt was playing a game against North Carolina State. I stayed in the dorm with the football players and liked what I saw, but still planned to go back and play football at Georgia Tech. But Red said, `No, I want you to sign before you leave here.’ So I ended up signing with Vanderbilt.”

During his freshman season, Curtis would not start, but found a great deal of playing time as a receiver. The Commodores would conclude the season (1947) at 6-4 (SEC, 3-3). Sanders squad would find victories over Northwestern, Alabama, No. 8 Mississippi, Auburn, Tennessee Tech and Miami (Fla.). Though freshmen athletes were generally ineligible for varsity play, a loophole in the rules would allow Curtis to play football as a freshman.

“We were eligible because at that time World War II had just ended and the rule was that if you were in school, you were eligible to play varsity ball,” said Curtis. “Sanders brought us in right after high school graduation and we reported to Vanderbilt in June. We went to summer school so we were eligible. We had a mixed bag of athletes. We had some guys that had been there before, but had been in the military.

“We had a hard core of guys that had been over seas fighting that joined the team. And there were about seven of us freshman that made the team, dressed and played some throughout the year. Actually for being freshmen we got to play. We didn’t play a lot, but we played in almost every game after the first three games.”

Curtis’ stats include six receptions for 124 yards and no touchdowns. That was second best behind all-SEC performer and Vanderbilt senior John North who led the Commodores with 11 receptions and 197 yards and one TD. Sanders ran a single-wing offense that didn’t allow for a great deal of passing.

In his sophomore season, Curtis earned a starting position as a receiver midway during the year. He solidified his starting role after his performance against Yale in New Haven. Another aspect of playing college football in this era was the expectance of playing on offense and defense. Curtis learned to play defensive end.

“You had to play both ways in those days,” Curtis said. “The thing that I went through was Red told me that I could play offense, and he was going to teach me how to play defense. The way he taught me was by having me come out 30 minutes before practice and hit heads with two guards who were pulling as blocking backs. The running back would take the ball and I’d have to make contact through the guards to tackle the back.

“I wasn’t very big back then. Actually nobody was as big as they are today. I was 172 pounds. There weren’t any facemasks and my face was full of scabs. I couldn’t eat and keep food down. After about four weeks of that I went down to see Sanders and said, `Coach, I think I’m going to have to quit. I just can’t take it. It’s a physical beating that I wasn’t expecting. I don’t think I can handle it.’ He said, `If you quit, where are you going?’ I told him I would go home. He said, `I know your daddy. If you quit, you better not go home.’ I started to think about what he said and he was right. So I stayed. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but I probably wouldn’t have played college football if it wasn’t for him.”

Vanderbilt would finish the season 8-2 (SEC, 4-2-1). The Commodores won their final eight games with key wins over Auburn, LSU, No. 15 Tennessee and No. 12 Miami (Fla.). Curtis led the Commodores in receiving with 259 yards on 12 catches. Those receiving numbers were seventh best in the conference. Curtis also collected three touchdowns.

At the end of the season, Sanders announced that he was leaving Vanderbilt for sunny California to coach at UCLA. Sanders had been at Vanderbilt in 1940-42, 1946-48 with a three-year interruption to serve in the military during World War II. Bill Edwards would replace Sanders.

“I was really disappointed when Sanders left,” said Curtis. “Actually the seven of us that came in as freshmen that were recruited by him, talked to him about going with him. He said that he didn’t want to get in the position of having the university say that he was stealing athletes. We were sincere about following him to UCLA. We bonded together in the fact that we were beginning to play a lot. But he just said no. That was his way of telling us we couldn’t make the team out there.

“A lot of people liked Bill [Edwards] a lot. He brought in an offense that gave me a chance to be a pass receiver because he went to the pro-type offense. It was the T-formation with wide-outs and a tight end. We threw the ball a lot. Bill was little different in the fact that he was a northerner. He thought the southern boys were slow and didn’t catch on quickly. He thought we were slow in picking up the change from single-wing to the T-formation. Bill never did know our names. For example, he called Jim Hutto `Hughto.’ Carl Copp was `Gopp.’ I was Bucky Curtis, but he called me `Bud’ the whole way.”

Curtis repeated as the Commodores’ top receiver as a junior. His 22 receptions for 446 yards were third best in the SEC. Curtis totaled five touchdowns and had four nullified by penalties. He tied with Ole Miss’ Jack Stribling for the highest number of TD receptions. The 1949 Commodores were 5-5 (SEC, 4-4) with wins over Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Auburn and Marshall.

“That was disappointing season for us since we had that great year as sophomores,” Curtis said. “We felt like with everybody coming back we would have a great season. With the change in coaches, I think we had a little mental letdown with the different system. The boys we had fit the other system better. I think that some of that crept into our thinking after we lost a couple of games. We had some positive things to take away from the year.

“The four years we were there, we never lost to Alabama or Auburn. That was always a good talking point. Bill Wade came into the picture and was a heck of a thrower. Jamie Wade [no relation] had been there. Our junior year was the first year that Bill had taken over. He was a sophomore and played in a few games as a freshman. Then he played a lot as a sophomore. Wade and [Babe] Parilli of Kentucky were the biggest throwers in the conference.”

Though Wade was a year behind Curtis, the pair would develop good chemistry and became one of the best passing combinations in the conference.

“That summer before my senior year, Bill and I worked out every single day running the stadium steps,” Curtis said. “On the field, he would take the ball with his five steps back, come back up a couple and I’d make a move. We must have thrown passes at least two hours a day. That was something that we did on our own because we were both in Nashville. That helped us a lot. About 90 percent of the time when I finished a break and turned around, the ball was about five yards from me.”

Going into his final year, Curtis was being touted as one of the top-returning receivers in the SEC and the country. He made the national sporting news in the third game of the season against No. 12 Alabama in Mobile. This is from an AP story after the game:

“Before the Alabama game in Mobile Oct. 7, a telegram was handed to Bucky. From his sisters, Nancy and Fralil, it said: `They tell us man can stop neither time nor tide. See what you can do about the latter today.’

“Bucky grinned. Four minutes later he had stunned the Crimson Tide with an 85-yard pass play, the fourth longest aerial touchdown in Southeastern Conference history.”

Vanderbilt upset Alabama that day 27-22 and Curtis recorded his best numbers for a single game with 196 yards on six receptions and two touchdowns. The 196 yards were seven short of the national collegiate mark at the time of 203 yards held by Iowa State’s Jim Doran set the previous year.

“Bill [Wade] had a great day throwing,” Curtis said. “I found a defensive back that I was fooling with double fakes and just kept working on him. Bill kept putting it there. That day we were three touchdown underdogs. Offensively and defensively we played very well. Just about every time that Alabama would get to the 20-yard line, we stopped them. We’d take over on offense and moved the ball. It was a good pass and catch day.

“That long pass was what we called a Z-and-in. I’d go down, take one step in like I was going to run a post route, then fake three steps to the outside and then cut back in front of the defensive back. Bill would hit me when I was coming down the middle with what ended up being a post route.”

Curtis’ 29.3 yards per reception average in 1950 continues as a SEC record today. The 85-yard TD pass is the fourth longest in Commodore history. The 1950 Commodores were 7-4 (SEC, 3-4). Victories were recorded over MTSU, Auburn, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Chattanooga.

“There was one play that Mac Robinson and I ad-libbed in the Florida game,” said Curtis. “Wade threw me a down-and-out pass on the left side while Mac was running a swing route. I caught the ball and the defensive back hit me. Mac was running the completion of his route so I lateral the ball to him. Mac started running with the ball down the field. I got up off the ground and chased after him.

“Mac was about to be tackled on the 20-yard line. I yelled at him and Mac lateral the ball back to me and I scored. Mac and I love to laugh about that play because it covered about 80 yards. That was a game we lost, but shouldn’t have. We gave that game away. Florida was the closest team to our size that we ran into. And that game was in Nashville.”

Curtis racked up several accolades after his senior year. He was a First Team All-American, First Team All-SEC, selected to the East-West Shrine game (captain for the East team) and selected to the Senior Bowl where he served as captain and was named the game’s MVP.

Said Curtis, “The thing that made me feel best of all was what my father said. He said, `I’ve been in athletics all my life as a coach and an athletic director. You are the first all-American I have ever known.’ I was captain of the East team and captain of the South team. Those things make you feel good because you are playing on teams with guys that you only have about 10 days or two weeks to know. Then to have them elect you captain was an honor.”

Curtis said that he had fair speed for a receiver, but his long stride was a deception that made him look faster than he really was and he had the ability to find an opening downfield.

The Cleveland Browns, who had won the championship in the previous year, selected Curtis in the second round of the NFL draft. He would have an opportunity to face his new teammates while playing against the Browns in the annual College All-Star game that was played from 1934-1976. Each year a collection of college all-stars would face the defending champions of the NFL. Curtis was selected as an all-star.

“That was the biggest disappointment in my athletic career,” said Curtis. “I don’t know why Herman Hickman, who was our coach, didn’t let me play in that game. I was first-string end during the two-week workouts and all of a sudden I was on the bench. I have often thought that maybe it had something to do that I had been drafted by Cleveland. There were a couple of us on that team that were drafted by Cleveland and didn’t get into the game. I was so heartsick that after the game I left as soon as it was over. I never saw Hickman ever again.”

However, Curtis’ journey into professional football would be put on hold with the Korean War in progress.

“I sure was looking forward to playing professional ball in Cleveland,” said Curtis. “Back in those days you didn’t have an agent and I had to deal with Paul Brown [Browns owner and coach]. Baby Ray, who was a tackle with the Green Bay Packers for 11 years and our line coach at Vanderbilt, heard Bill Edwards tell me, `When you talk to Brown, don’t give him any trouble. Just take what he says and sign the contract.’ When I came out of Edwards’ office Baby Ray said to me, `Don’t listen to that. Tell him you want $12,000 or $15,000 because you are not going to get that much. Then he will negotiate with you.’

“I had made the Browns team during the preseason, and then I was drafted into the military before the season began. It was just horrible and a nightmare. Paul Brown told me not to worry about the draft that he had people in Washington that would work that out. Then they came back to me a few days later after workouts. I received a telegram from General [Lewis] Hershey that I had five days to report into the service. So Brown told me to find out where I was being sent. I told him I was going to Fort Jackson. Brown said, `Lord don’t go there, they don’t have football.’

“He told me to go somewhere where you can keep your legs and wind in shape. I called the Air Force and they said I had to join for four years. I said I didn’t want to do that. I had run into the best recruiting salesman and the next thing I knew I was in the Navy for four years. He had sold me on the fact that I could apply for OCS [Officers Candidates School] and would only have to serve two years. I did that and went through all the stuff to get the OCS appointment, but I failed the physical. I had a crooked arm and not enough teeth. I could have one, but not both. So I ended up in the Navy for four years.”

Curtis would spend his entire four years in San Diego without being sent to Korea. He played football, basketball and golf on the service teams. When his service time expired, Curtis looked into going back to Cleveland and playing professional football again.

“I had stayed in touch with Brown and every time they played the Rams in Los Angeles, he had given me a bunch of tickets,” said Curtis. “I’d take some of my buddies from the Navy football team to watch Cleveland play the Rams. I had already talked to him about coming back. Brown told me they would renew my contract, which was $8,500. I said, `Wait a minute. I’ve got four more years experience.’ Though it was in the Navy our service team beat the Washington Redskins, the 49ers, lost to the Rams 14-7 in exhibition games. I had obligations since I was married with a kid.

“He told me he would increase the contract to $9,000. The Canadian Football League came down to talk to Bill Wade about jumping from the Rams to their league, but he didn’t do it. So Wade told them about a friend who is an end in San Diego and they should talk to him. I knew that I was only going to play for two years because I was going to work for my father-in-law in Cincinnati. I talked to Toronto and they were paying nearly twice as much as down here.

“I signed up there for $15,000 and got a bonus for making the all-star team. It turned out to be a nice situation and in the second year I received a nice raise. They just assumed that I was coming back. I told them I had made a commitment to my father-in-law and I was finished with football. My wife got to love Canada and was pushing me to go back. But her father was adamant that if I didn’t come back, he wasn’t going to let me work for his company. So I stayed with my commitment and didn’t go back to Canada.”

Curtis did go to work for his father-in-law who sold the company to International Paper. Curtis worked for that firm for 29 years and later purchased a company himself. He was selected to the 2010 Class of the Vanderbilt Athletic Hall of Fame and was Vanderbilt’s SEC Legend of the Game in 1997. The retired Curtis was asked to look back on his playing days at Vanderbilt and talk about his fondest memory.

“I established a lot of friendships when I was at Vanderbilt,” said Curtis. “My father-in-law told me to make sure that when you leave college, that you don’t leave the relationships that you built. I didn’t, and that would have to be the biggest thrill I got out of being a member of the Vanderbilt alumni. The people I met there I’ve really enjoyed, respected and have a lifetime relationship.”

If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.