Follow along with Vanderbilt junior Kailia Utley and the @VandySwimming team on their recent international education trip to New Zealand. 🏊♀️🇳🇿

Throughout the trip, the team went on multiple cultural experiences and educational trips within the country. #AnchorDown pic.twitter.com/j1B67jWT5w

— Vanderbilt University (@VanderbiltU) August 17, 2023

Around the World in 90 Days

by Graham HaysVanderbilt student-athletes traveled to six countries across three continents on summer international trips, bringing them closer together and expanding horizons

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — By the time the Vanderbilt soccer team returns home from this fall’s SEC Tournament, it will have traveled approximately 5,000 miles during the season. The Commodores will then hope to trek a few more to the Women’s College Cup in Cary, North Carolina.

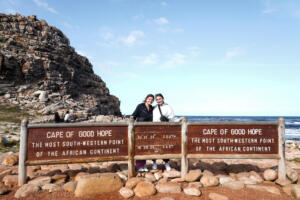

But none of that will match the summer odometer, which registered approximately 8,000 miles on the team’s trip to Cape Town, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.

And yet, soccer student-athletes can barely claim bragging rights as the most-traveled Commodores; they just managed to edge out the swimmers, who headed the other direction out of Nashville on their own 8,000-mile New Zealand odyssey.

Road trips are nothing new for student-athletes, who grow up traveling to tournaments and camps and balance their coursework with trips around the conference and country. But this summer, in addition to headphones and travel pillows, passports were required gear.

NCAA rules allow collegiate teams to take an international trip once every four years. With the help of each team’s donor-supported Excellence Fund, Vanderbilt teams seized the opportunity en masse. In May, shortly after completing their exams, soccer student-athletes traveled to South Africa and the United Kingdom. At the end of that month, swimming student-athletes set off for New Zealand. In June, lacrosse student-athletes toured the Czech Republic and Germany. Finally, shortly before classes began anew, women’s basketball student-athletes visited Italy.

Each trip featured opportunities for student-athletes to compete against international peers, conduct clinics to share their sport with younger athletes and see new places—from historical sites to natural wonders. But beyond the specific details of the itineraries, travel provided the means to continue journeys that drew students to Vanderbilt in the first place—journeys at the heart of the university’s historic Dare to Grow campaign, which celebrates the collaborative spirit inherent in athletics as an avenue for fostering lifelong learning and growth.

Journeys of learning, connecting, competing, experiencing and bonding that continue after returning home and long after their time in the pool or on the court or field comes to an end.

“It’s very easy to feel like you’re in a bubble and in your comfort zone when you’re at home in your city and community,” soccer senior Tina Bruni said. “But once you step out of that and open your eyes, you can see similarities and differences, challenge yourself and grow individually. You see things that you want to implement in your lifestyle that you didn’t even know existed. You gain perspective on how blessed we are to have this life, and how we should really go out and experience it and open our eyes to what’s around us.”

Soccer’s Mia Castillo, left, and Rachel Deresky, right, in South Africa (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt Athletics).

Learning …

In many ways, a week in Prague and Berlin sounds like a trip designed for lacrosse senior Haley Gochnauer, an English and law, history and society double major. The capitals of the Czech Republic and Germany, respectively, are focal points of Central Europe’s story and awash in history dating back almost a millennium. In addition to the opportunity to play and teach lacrosse, the trip included stops at sites like Prague’s Old Town and, near Berlin, Potsdam’s New Palace, which was home to generations of Prussian and German royalty. All of it was a history buff’s dream.

But for Gochnauer, another stop meant confronting—and sharing—history that doesn’t fit smoothly in a snapshot or social media post. History that is personal and painful and all the more important for it.

As a Jewish studies minor, Gochnauer completed a research paper last spring on post-traumatic stress disorder among Holocaust survivors. As a Jew, family and community history long ago imparted the full tragedy of the time, and the far longer history of the antisemitism that fed it. She learned about too many places like Terezin, a former concentration camp approximately 30 miles outside Prague that the lacrosse team visited.

Lacrosse student-athletes visit the Terezin Memorial in Czechia (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt Athletics).

Although not an extermination camp like Auschwitz-Birkenau, Terezin was a transit camp and Jewish ghetto in which tens of thousands died as a result of torture, malnutrition and poor conditions. Whether they died on site or were subsequently killed in extermination camps, few of the estimated 140,000 men, women and children who passed through survived the war.

Visitors to the memorial and museum walk through barracks where prisoners lived crowded together. They see not only the names of children in the camp but their drawings and scribbled poems. They see the isolation cells for prisoners who fought back or committed sometimes-imagined infractions. A member of each tour group is invited to step inside and describe to those outside the pitch-black void that envelops them when the door slams shut.

Walking through the grounds, visitors also see the haunting phrase “arbeit macht frei” painted above an archway beneath which prisoners walked each day.

“That was a heavy day and a very hard thing for me to see,” Gochnauer said. “I can hear about it and read about it in my books in America and be completely untouched from the actual physical reality—this is where people walked, and these are the places people went through.”

When she first heard about the trip abroad and the scheduled visit to Terezin, Gochnauer worried that it might be better to experience something like the museum and memorial with her own family. She would still welcome that opportunity for other sites, but seeing this one with what she calls her second family proved meaningful. Her closest friends looked out for her before, during and after the tour, able to sympathize if not experience it in quite the way she did. And at the same time, seeing it with her brought them that much closer to seeing it through her eyes.

Lacrosse’s Ashley Sampone, left, and Ashley Sampone, right, listen to a guide at Terezin (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt Athletics).

“It was definitely important for my team to see as well,” Gochnauer said. “It would have been difficult to know that we went to Germany but just ignored that side of history—because I think that it is a crucial piece to world history in general. All of my teammates were really respectful of the camp and of me and understanding what the day meant.”

Connecting …

International travel is a natural fit for soccer. FIFA, the sport’s governing body, has more members than the United Nations. And yet, growing up in California, Tina Bruni didn’t always feel she was part of a global game. Apart from the Women’s World Cup and Olympics, international soccer available on television was more often men’s soccer.

This summer, South Africa showed the world how that is changing. In August, South Africa’s Chrestinah Kgatiana scored a stoppage-time winner in the Women’s World Cup that eliminated Italy and sent the African side through to the knockout round for the first time in its history. Even in a tournament marked by upsets pulled by national teams long overlooked abroad and starved for resources at home, South African success stood out. In the players’ joyous celebrations, the world saw how truly global the game could be.

Hout Bay United Football Community grounds in Hout Bay, South Africa (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt).

It also wasn’t the first time this summer that South African soccer offered that lesson. A few months earlier, far from the bright lights of a major tournament, Bruni and her teammates experienced something similar in the Cape Town-adjacent community of Hout Bay.

The Hout Bay United Football Community mission is to create “the leading public benefit organization for youth development and education while also achieving successfully managed football.” The organization purposely chose “community” instead of the ubiquitous “club” as the final part of HBUFC to underscore its commitment to serve the area in ways beyond wins, losses and draws. Encompassing both an affluent and majority-white suburb and the impoverished and majority-Black townships of Imizamo Yethu and Hangberg, the area is, as Hout Bay United puts it, “a true reflection of South Africa” and “represents not only the racial and cultural diversity, but also the economic divide with rich living alongside poor.”

In their day with Hout Bay, the Commodores toured not just the club’s soccer fields and training environment but dormitories, classrooms and online learning spaces. Stepping beyond the club confines, they explored the surrounding communities that shape its mission. Guided by staff members and players from the senior team who grew up in Imizamo Yethu and Hangberg and could offer context on history, current challenges and successes, Bruni and her teammates visited homes, markets and more. They saw for themselves how the club was shaped by and is helping shape the community, providing youth with a ladder up on education and giving residents of every background a place to come together around the game.

Finally, Bruni and her teammates returned to the Hout Bay United complex and helped put on a clinic for local youth, staging drills and organizing scrimmages for boys and girls.

“There were definitely some nervous ones, but a lot of them were very outgoing and very happy that we were there,” Bruni said. “It was heartbreaking to say goodbye. They were all giving us big hugs and smiling for pictures. They were incredible, every single one of them. They were really willing to learn. They were excited for the opportunities with new faces, and we were just as excited to be there with them.”

Earlier during their nearly two-week stay, Vanderbilt played an exhibition against the University of Western Cape, the first South African university to award an honorary doctorate to Nelson Mandela and where fellow Nobel Peace Prize laureate Desmond Tutu was formerly chancellor. Bruni and her teammates also conducted a soccer clinic in conjunction with Oasis Place, a nonprofit organization focused on helping the economically and socially marginalized Cape Flats community near Cape Town through a variety of social programs, including soccer.

“Everyone really welcomed us into their community, and we got to see how something like soccer really connects us,” Bruni said. “No matter the differences in our culture, our lifestyles, how we could all bond together through soccer.”

Soccer student-athlete Kate Devine with local children at Hout Bay United (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt Athletics).

During the World Cup, a group of largely Black South African women demonstrated soccer’s potential to inspire and empower—to overcome the challenges of a country’s troubled history on race relations and a sport’s troubled history on gender equality. Over the course of nearly two weeks, young South African soccer players, especially girls, shared a similar message in showing Vanderbilt student-athletes that their sport has the potential to bring people together.

“This trip really opened my eyes to how much women’s soccer is also global,” Bruni continued. “Everyone is brought together by this sport, no matter what. Even when we were playing with the kids, it didn’t matter if you were male or female, we were scrimmaging against each other and having fun. It was really incredible to see.”

Competing …

Basketball is increasingly as much a global language as soccer. There is hardly a corner of the world in which the sight of two teams racing up and down the court looks incongruous.

Even when the trip to the gym begins by boat.

For the women’s basketball team, traveling by watercraft was just one of the ways that game day in Venice, Italy, was a little bit out of the ordinary. Another was the tour of the city that occupied the morning, an excursion that took the place of the film study and walk-through and rest that more often accompany SEC preparation. But once the game against local opponents tipped off, aside from adjusting to a slightly more physical European style, Venice might as well have been Fayetteville or Tuscaloosa. Basketball is basketball. Competitors compete.

With five freshmen, including Poland’s Aga Makurat, and two transfer student-athletes, the women’s basketball team benefitted from the opportunity to get a head start on forming the on-court chemistry necessary to compete in the SEC. Coach Shea Ralph and her staff used the exhibition games to create small moments of adversity. Early in one game, they pressed and trapped full court—defensive concepts they’ve barely had time to introduce, let alone hone. Mastering the carefully choreographed rotation necessary for a press to work wasn’t the point. The goal was to see how the student-athletes figured out how to adapt and communicate.

The Commodores won in Venice and again against a different team in Rome. But more than results, competition made them better by helping them better understand each other.

“Even though I was already starting to learn a little bit about this at home, playing against other teams let me see what my teammates like to do—their strengths and weaknesses,” graduate student Jordyn Cambridge said. “As point guard, that’s really crucial information for me to know. I want to make sure I’m putting my teammates in positions where they’re going to be successful and where they’re not going to have to do something that’s too far out of their comfort zone.”

Jordyn Cambridge returned to the court for Vanderbilt in Venice (Leah Dusterhoft/Vanderbilt Athletics).

And afterward, when the game was done, basketball brought strangers together—crafting a TikTok video with opponents, swapping gear as mementos or simply standing around the court and talking about life.

“I’ve really only ever been in America,” Cambridge said. “Going somewhere else and still being able to see that we’re interested in the same things, have some of the same goals—and we’re just getting there in different ways—that was pretty cool for all of us to be able to bond over that.”

Few athletes anywhere in the world have traversed quite the same route as Cambridge or stuck as doggedly to their goals. The Nashville native arrived at Vanderbilt in 2018, having already overcome a torn anterior cruciate ligament—which led to the diagnosis of a rare joint disorder that slowed her recovery. Near the end of her sophomore season, she tore the ACL in her other knee. Last summer, shortly before beginning her fifth year on campus, she tore her Achilles tendon, ending her season before it began.

An NCAA waiver granted the graduate student pursuing her master’s in human development studies a sixth year of eligibility. The Italy trip, almost exactly a year after her Achilles injury, would mark her competitive return (she had been participating in full-court, five-on-five situations in practice). In consultation with coaches, and wanting to ensure that conditions in the Venice gym were optimal for her return, the training staff held off on clearing her until the team arrived for the game. They settled on a total of eight minutes, two per quarter.

After so many comebacks, and all the setbacks, frustrations and lonely hours of rehab that come with them, Cambridge described herself as almost emotionally detached from the milestone. She had learned the perils of getting too high or too low in a given moment. But for the Nashville native, what mattered much more was the opportunity to play on that day in that particular gym. Her experience had taught her to savor special moments when they come.

“I was ready to get out there and play,” Cambridge said. “I knew that I at least wanted to play a couple minutes while we were in Italy—because I’m never going to get another chance to play in a different country. So, either I get to play 30 seconds here, or it’s never going to happen for me. I was excited for that. It was another of the once-in-a-lifetime opportunities over there.”

Vanderbilt’s pregame meal was a little bit different in Venice (Leah Dusterhoft/Vanderbilt Athletics).

Growing …

Like their soccer counterparts, by crossing the equator in May, Vanderbilt swimmers experienced an extra autumn in their year. But after donning layers of warm clothes and rain gear to trek through mountains, beneath cloudy skies and a cold rain, Kailia Utley and her teammates could be forgiven for thinking winter had arrived early in the Southern hemisphere.

Midway through their stay in New Zealand, the team embarked on an all-day hike in the Tongariro National Park. The weather, which delayed the start of the adventure, was miserable for much of the hike. But after hours on the trail, their patience and persisted were rewarded.

“The clouds started to part, and the top of the volcano came into view, the sun shining down on it,” Utley recalled. “Everyone turned around and was just speechless. It was one of those moments you could never have expected to have—that was not what you had been looking at the past four hours. It just reminds you how much hard work and effort can lead to something magical. I mean, some of my teammates are not outdoorsy people—at all. They were not huge fans of hiking either. And even for them, they were like, ‘That was worth it.’”

While the trip began in Auckland’s urban environs and included a meet in the familiar confines of an aquatics center, the team spent the bulk of the two-week trip exploring the natural world around Rotorua and Whakapapa. The former is a lake and literal hotbed of geothermal activity, and the latter is near Mount Ruapehu, an active volcano that rises more than 9,000 feet.

In the process, with help from Guil Gualda, professor of earth and environmental sciences and trip participant, Vanderbilt swimmers became amateur geologists—much to the annoyance of drivers stuck behind the bus that stopped at seemingly every rock outcropping it passed.

“It was really interesting to see that progression in a short amount of time, for something that most of my teammates were not interested in before and aren’t necessarily going to pursue in the future,” Utley chuckled. “Some of them surprised me in how much they loved it—taking notes about a rock. And it was really interesting when they’re showing us things like rocks that came from volcanoes three kilometers away.”

The daylong hike through the volcanic landscape was the culmination of the mini course in some of the forces that shape the world around us. It also proved useful in learning about the bonds that hold a team together. Trained guides monitored the weather and ensured the safety of the traveling party, but hiking roughly 20 kilometers through rugged terrain on the other side of the world tests a person’s resolve more than a stroll on the boardwalk at the beach. When the distance, weather or steep spots pushed people out of their comfort zone, teammates were there with a word of encouragement or a reassuring hand.

“It’s trying to help them through a fear that you wouldn’t necessarily have known that they had,” Utley said. “I didn’t know that some of my teammates were that uneasy with heights, for example. That specific fear isn’t something we’ll ever come across during swimming. But now I know what sort of pep talk they might need in a tough spot or if they’re afraid of something. I think that was a very defining experience for a lot of people.”

Bonding …

Swimming might appear an odd choice for a discussion of camaraderie. At least compared to other team sports, it leans heavily on individualism. Relays aside, once an athlete is in the water, as Utley noted, it can feel as if it’s just you and the black line at the bottom of the pool. But that potential isolation is also why camaraderie and collaboration are all the more important. You’re ultimately responsible for how quickly you cover a length of the pool, but your teammates have everything to do with your state of mind entering and exiting the water.

“Sometimes I get nervous, and then I get a little bit too much in my head,” Utley explained. “Having that team—that you really trust, and that supports you—brings you back. You want to see them do well. You want to see them push through and achieve those goals that they have. And when you’re close to those people, seeing them do well helps you too.

“It’s fun, when you’re racing, and you can maybe catch a glimpse of your teammates at the end of the lane. It helps take you out of the individual mindset, even for just a second, and gives you a broader perspective.”

Soccer in South Africa (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt Athletics).

You can form those bonds on campus, studying for a final, talking in a locker room, exploring Nashville or watching movies. But the very act of traveling—say, leaning on your neighbor’s shoulder through a 16-hour flight from Dallas to Cape Town—concentrates the process.

On the soccer team’s final day in South Africa, Bruni and a few of her teammates woke up early to go for a run on a nearby beach and watch the sun rise. It wasn’t part of any itinerary, and it could just as easily have been the sun rising above the ocean near Bruni’s California home. But their spontaneous decision led to an ultimately unforgettable shared memory.

Lacrosse on a bike tour in Germany (Laura Topp/Vanderbilt Athletics).

Traveling with friends can lead to memories that have very little to do with the location and everything to do with the company. In Potsdam, the lacrosse team rented bikes and split into groups to tour the city. Gochnauer remembers the palaces and castles they pedaled past, the grand fountains and parks. But in this instance, it wasn’t the history that mattered.

“I’m just … I’m with my people,” Gochnauer said. “I could just be biking around anywhere, and it would still be super fun. This is one of the closest teams you can meet. Everybody likes to say they’re close, but we truly feel it. And whether we were just going out to eat or walking around the city, it was a great experience with everybody. It felt like, ‘Yes, these are my best friends.’”

Travel brings people together. It increases understanding of the world, its history and the people who call it home. But it also helps people understand themselves and where they fit. A bike ride through Potsdam or a mountain hike in New Zealand will pay dividends this year for teams that now are closer than ever before.

“I think a big part of life is new experiences,” Gochnauer said. “And I think travel is a great opportunity to acquire those experiences.”

Just as a summer of travel will help on the lifelong journey that awaits.

“All my stamps in my passport are because of Vanderbilt,” Cambridge chuckled. “I’m very appreciative of that.”

Help support future travel, development opportunities and current priorities by giving to a Vanderbilt Excellence Fund: Women’s basketball | Lacrosse | Soccer | Swimming | All sports

About the Dare to Grow Campaign

Launched in Vanderbilt’s 150th year, Dare to Grow is a $3.2 billion comprehensive campaign, the most ambitious in university history. The campaign will succeed through three essential pathways—Destination Vanderbilt, Discovery Vanderbilt and One Vanderbilt—and by furthering the culture of belonging, innovation and collaboration that defines the Vanderbilt Way. Learn more at vu.edu/daretogrow.