A Champion's Drive

by Graham HaysGordon Sargent arrived at Vanderbilt as a prodigious talent. He won a national championship by striving to be even better.

Reigning NCAA individual national champion Gordon Sargent will compete April 6-9 at the Masters Tournament at Augusta National Golf Club in Augusta, Georgia. This profile originally ran in November.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — Eight minutes. Gordon Sargent estimates that’s about the time that elapsed between his final putt in the final round of stroke play during this year’s NCAA Division I Men’s Golf Championship and the start of a four-way playoff to decide the individual national championship.

Eight minutes, give or take, to push away thoughts of a missed putt on the 18th hole that would have clinched the title without a playoff. The freshman hadn’t been nervous standing over the putt. He’d had a good read on the putt. He’d thought the ball was going in from the moment it left his putter. Watching nearby, Vanderbilt head coach Scott Limbaugh had too.

Instead, the ball slid by the hole, leaving Sargent and three competitors tied for first place.

Mind you, the individual title wasn’t Sargent’s main goal when he arrived in Scottsdale, Arizona, for the tournament this past May. College golf is primarily a team sport, and the trophy that matters most is the one that’s handed to the champion team. Yet by the start of the fourth and final round of stroke play, Sargent and his teammates were already all but assured of qualifying for the head-to-head match play round that decides the team championship. That job was done.

The individual title, awarded to the golfer with the best score through stroke play, was still there for the taking. And if there is something to win, whether it be bragging rights in a round with his dad and brother or an NCAA individual title, Sargent’s competitiveness takes over.

Not much more than eight minutes after he walked off the green at the end of regulation, he again teed up his ball on the same hole—No. 18 was the playoff hole. Rather than play a conservative shot and wait for the other golfers to make a mistake, the freshman ditched the cautious approach and pulled out his driver. The shot that followed will live in Vanderbilt lore, at least if Limbaugh’s text message history is a good first draft of history.

“It sent a message to everybody on that tee box that ‘I’m about to go take this thing,’” Limbaugh recalled of Sargent’s drive. “I don’t know what they said on TV, but the second he hit that drive, I had about 25 text messages from former players, just saying ‘OMG’ or going crazy about the ball speed. That swing, and then the courage he showed with the wedge to that pin—if you’re not there, you can’t understand what a big boy golf shot that was from a freshman.”

This time, Sargent sank his birdie putt to win the playoff and the title. He not only won Vanderbilt’s first individual national championship in golf but its first individual title in any sport since track and field standout Ryan Tolbert in 1997.

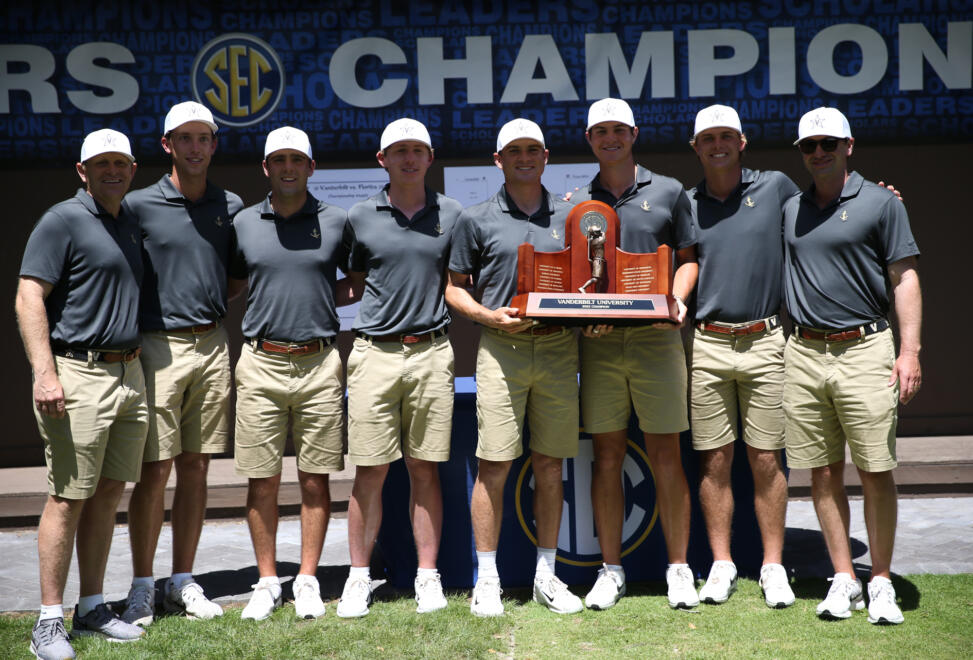

Rampant success can appear to be Sargent’s default setting. In addition to the individual national title, he helped lead Vanderbilt to the NCAA semifinals and a second consecutive SEC championship. He received the Phil Mickelson Award as the nation’s best freshman and represented the United States in recent months in the prestigious Palmer Cup, alongside Vanderbilt teammate Cole Sherwood, and in the World Amateur Golf Championship. One of the nation’s most highly touted recruits, he is now among collegiate golf’s top-ranked players.

And yet the roots of his success can be seen in those eight minutes in Scottsdale. In using the tools honed during his first year at Vanderbilt, Sargent embraced the discomfort of disappointment and emerged bolder and better for it. He brought to life Vanderbilt’s motto: dare to grow.

"When it’s a four-man playoff, you’ve got to expect that you’re going to have to do something—they’re not all going to give it to you."

Gordon Sargent

A passion to improve

Fred Major was one of many fans who followed Sargent’s progress from afar during the national championship this past spring, catching a few holes on television or following along online. And while he might have marveled at his former pupil’s nerve in taking on the four-man playoff, he wasn’t surprised by how it happened.

Major taught AP statistics at Mountain Brook High School near Birmingham, Alabama, when Sargent was a junior in the class. One of each year’s first exams centers on experimental design and sampling methods, the questions mostly requiring short essay answers. It is also an annual stumbling block for students, most of whom enter the class expecting more math than essays.

Like most of his classmates, Sargent struggled on the test. Major doesn’t recall the grade, but he does recall handing the corrected exam back to Sargent. Specifically, he remembers Sargent looking from the test to Major and back to the test, then saying simply, ‘OK, I’ve got this.’

Good to his word, Sargent breezed through the rest of the class with nearly flawless marks.

“I knew in that moment why he was such a darned good golfer,” chuckled Major, who described himself as an avid, if not always successful, practitioner of the sport. “There was no emotion, it was just as if he had hit a ball in a bad spot, but he knew he could get out of it. From then on, I couldn’t tell you what he changed, but he knew he had to change something. And everything after that he completely blew out of the water.”

By the time Sargent stepped foot in Major’s class, he was far from anonymous in Mountain Brook. Over the years, people around town had gossiped about some local freshman or sophomore who appeared poised to be the next big star in one sport or another. But the stories rarely started as early as middle school, as they did in Sargent’s case.

Sargent’s dad introduced him to golf almost as soon as the boy was able to come with him to the local course, cutting down a putter to fit the child’s dimensions. When he was 9 years old, Sargent entered the 10-and-under division of the Future Masters in Dothan, Alabama, a staple of youth golf in the region for more than 70 years. He did well. More importantly, he enjoyed the thought of doing even better.

“I just remember I really enjoyed it, and then I went back the next year and played a lot better,” Sargent said. “That was when I knew I could continue to get better. I feel like I’m pretty driven when it comes to wanting to get better, so even then, seeing the improvement over that year was a little eye-opening.”

By 2018, he was back in Dothan to win the Future Masters division for 15- and 16-year-olds. A year later, he was Alabama junior champion. A year after that, he won the first of back-to-back state amateur championships and competed in the renowned United States Amateur Championship. By his senior year at Mountain Brook, he was named USA TODAY Male Golfer of the Year as part of the organization’s annual high school sports awards.

Known early in his junior career for playing with polish beyond his years—keeping the ball in play and chipping and putting with precision—Sargent added world-class distance as he grew into his body during high school. He arrived at Vanderbilt as the most heralded recruit in what Limbaugh described as the most decorated class in program history.

Another ‘I’ve got this’ moment

Weeks into Sargent’s collegiate career, Vanderbilt traveled to the Birmingham area for the SEC Match Play Championship. Playing at his home course, Shoal Creek Club, Sargent had a golden opportunity to further cement his budding legend. Instead, he struggled, at least by his self-imposed lofty standards. He won his singles matches in the quarterfinals and semifinals, but he lost decisively in the championship match.

By his own telling, Sargent struggled to control his emotions that week. His body language betrayed him, and his focus wavered. With a decade of experience at Vanderbilt and nearly a decade more in collegiate coaching beyond that, Limbaugh said it wasn’t anything out of the ordinary for a freshman. Still, he recalled explaining to Sargent that there is “a certain way that champions think,” an approach that has been highly successful for the Commodores.

“He didn’t yell at me or anything, but he told me it was going to have to change, or it wasn’t going to get any better,” Sargent recalled. “From then on, it was about trying to work on that. It was a matter of understanding that how you act does not need to revolve around your golf game because it’s about much more than that. Obviously, you want to show emotion when you care, but you can’t let it take over.”

Four months later, Vanderbilt opened the spring season at The Prestige, an aptly named competition in La Quinta, California, that featured many of the nation’s top programs. Amid often windy conditions in the desert, Sargent endured an up-and-down week. In college golf, each team sends out five student-athletes, and the top four scores count toward the team total. On the middle of three days of competition in La Quinta, when the winds were at their fiercest, Sargent finished with the team’s fifth-best score—the dreaded drop score.

Yet even amid the struggles, Limbaugh saw no hint of sagging shoulders or frustration. And rather than let the difficult day snowball, Sargent reacted the way that his old stats teacher might have recognized. The next day, he shot a 65, 18 strokes better than his previous round and the lowest score of any of the more than 100 golfers in the event’s three rounds.

After teammates Reid Davenport, Matthew Reidel, Sherwood and Jackson Van Paris picked him up the first two days, he returned the favor to ensure that the Commodores cruised to victory by 10 strokes.

“He still always finds a way to get to where he’s trying to get to,” Limbaugh said of the growth evident in California. “And as the spring went on, he became more and more comfortable with being one of the best players on a highly ranked team.”

"He had the presence and the ability to change the group so that everybody was taken care of and treated equally.”

Fred Major, Sargent's former high school teacher

The benefits of collaboration

Competitive golf in the popular imagination is an individual pursuit. Outside of a handful of international events celebrated partly because their team formats differ from the norm, Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods and others gained their legends through feats of rugged individualism—caddies notwithstanding.

From that first taste of competition at the Future Masters through his amateur titles and accolades, Sargent, too, demonstrated comfort with striving for singular excellence. And again, that carried over from the course to the classroom and beyond.

As high school seniors, Sargent and several of his friends signed up for Major’s computer science principles class. It represented an opportunity for them to get a head start on college requirements while making the most of their remaining time together at Mountain Brook. Yet when Sargent learned that only the credits from a higher-level AP computer science class would fully transfer to Vanderbilt, he didn’t hesitate to switch classes and follow a more solitary path.

“He was going to take whatever he had to take to get the credit, instead of taking the lower course and having fun,” Major said. “He would have learned a lot in my class, but he was going to push himself to do the absolute max, while still taking AP calculus and all these other top-level courses.”

Still, there was something about collaborative environments that he craved as much as the rewards of individual pursuits. Growing up, he always tried to play with older, better players, seeking knowledge he didn’t yet have to sculpt the skills he wanted. And before winning an SEC title at Vanderbilt, Sargent and his Mountain Brook teammates won a high school state title together. Off the course, Major never saw him struggle when junior tournaments took him out of school for days at a time and he had to review lessons on his own. But he also saw someone who was at his best when able to bring out the best in those around him.

“If somebody wasn’t being treated the way they were supposed to be treated, he took issue with it and straightened it out,” Major said. “Not overtly and not in a mean way, but he had the presence and the ability to change the group so that everybody was taken care of and treated equally.”

Sargent has already experienced the world that awaits him beyond college golf, most recently in the World Amateur, when he competed on the same course that just four years ago hosted the world’s best in the Ryder Cup. Like more than a few former Vanderbilt golfers, he’ll eventually test himself in the somewhat solitary world of professional golf. It is a future that excites him, a challenge he’s eager to experience—in due course. Because it’s also a future that reinforces the fleeting quality and permanent value of his presence as part of a team, when he’s able to bring out the best in those around him. And when they are able to return the favor.

“If you ask anybody on this team to do something for you, they’re going to do it, which I think is really cool,” Sargent said. “And we’ve got two great coaches who will do anything for you, if you just want to talk about life or get some golf out there. There are so many people around you in college golf, which is different than junior golf and pro golf. There are so many resources and people who want to see you succeed. That’s humbling, and it takes the pressure off. And it makes it better when you succeed.”

Eight minutes in Scottsdale

Even before his first potential winning putt missed the mark on the final hole in regulation in the NCAA event, Sargent labored through a difficult round. After back-to-back rounds of 68 to take the individual lead, he would sign his scorecard after recording a 74 over the final 18 holes. On a day when few competitors broke 70, he battled just to keep his head above water.

Limbaugh walked with him throughout the round. And earlier in the day, at the team hotel, Sargent spoke at length with William Kane, a staff member with College Golf Fellowship.

He said, “This round’s not going to define you as a person,” Sargent recalled of the conversation with Kane. “Just go out there and play your game and let things happen. If it’s meant to be, it’s meant to be. So just keeping giving yourself opportunities.”

Entering the playoff, an opportunity remained. Strong closing rounds from his teammates kept Vanderbilt atop the overall leaderboard, guaranteed its place in match play and freed him to play without any added stress.

He and Limbaugh discussed using a 3-wood off the tee for the playoff hole, a lower-risk strategy that would have paid dividends if the pressure forced his competitors to make mistakes. Sargent eventually told his coach he couldn’t do it. He wanted to hit driver. After walking every hole with him that day, Limbaugh knew it wasn’t a rash or emotional decision. It was the calculated logic of someone who understood his strengths and how to use them.

For a moment, he thought his drive might drift toward a water hazard, but it landed softly and left him in a position to use his second shot to set up a birdie attempt.

“When it’s a four-man playoff, you’ve got to expect that you’re going to have to do something—they’re not all going to give it to you,” Sargent explained.

Success can seem like it comes easily to Gordon Sargent. But in the span of about eight minutes in Scottsdale, he showed just how hard he’s worked for it.