Sept. 1, 2010

Commodore History Corner Archive

Commodore History Corner Archive

There is a saying in sports that nice guys finish last. But, seeing through Vanderbilt’s disappointing four-year record under the late John “Jack” Green (1963-66), the head football coach was always a winner. His high moral character and integrity were more important to him than winning football games.

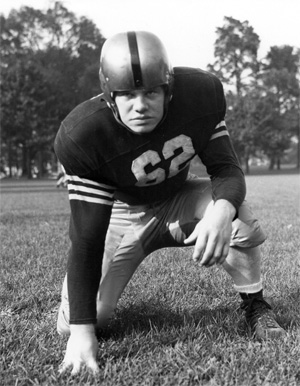

Born in Kent, Ind., Green played his high school football at Shelbyville, Ky., winning All-State honors in 1941 as a quarterback. He enrolled at Tulane University in 1942 where he played on the varsity as a freshman before receiving an appointment to West Point.

Green became a part of college football history as a member of the great Army teams of 1944-45. The Black Knights would be undefeated and national champions in each season. Green was selected as an All-American and Army captain as a senior in 1945.

“I met Jack in the summer of 1945 before his senior year at West Point,” said Jeanne Green, Jack’s wife who lives in Nashville. “I didn’t follow college football then at all. I had no idea who he was. I said, ‘What do you do other than going to class and having formations?’ He said, ‘I play a little football.’

“In the spring of 1946, before he graduated, he had a lot of leave time. I lived in Englewood, N.J. at the time and that’s 50 miles away from West Point. He came to down a lot of weekends to visit my family and me. One day one of my uncles, who was up on college football, said to me, ‘Is this the Jack Green who was the captain of the Army team?’ I told him I really didn’t know. He said you don’t know that he was a great football player? I said I don’t know anything about it. I really did not until later.

“When Jack would be there on the weekends, we’d go into New York City and people would actually stop him on the sidewalk to ask him for his autograph. Everybody knew about Army football then because they were the No. 1 team in the country. After he graduated, he went to Fort Benning and we were married in February 1947. I never saw him play football. He didn’t have time for girls or anything else.”

Coach Earl Blaik and Heisman Trophy recipients Doc Blanchard and Glenn Davis led those great Army teams. The 1945 team, captained by Green, is considered one of the greatest football teams ever assembled. That squad was 9-0 with a 48-0 victory over a highly rated Notre Dame team.

The Black Knights offense scored 412 points while the defense only allowed 46 tallies. At season end they were declared the national champions. Though Jeanne Green never saw her future husband play football, she did have quite an experience at one of college football’s most historic games. In 1946, No. 1 ranked Army played No. 2 ranked Notre Dame in Yankee Stadium.

“Jack had already graduated and flew up with a bunch of guys from Fort Benning that he had played football with at West Point,” said Mrs. Green. “They came for that game. I had a ticket up in the stands and Jack and all the guys were on the field with the team and his coaches. The game ended up 0-0 and everybody was euphoric over the fact that Army had really beaten Notre Dame. Jack and the guys went into the dressing room after the game. Jack completely forgot all about me.

“General (Dwight) Eisenhower and some men were walking around the stadium after the game. This was a half-hour or longer after the game. I was the only one sitting there. General Eisenhower came over to me to see why I was there. I told him I was waiting for Jack. General Eisenhower told one of the men go to the locker room and get Jack.

“Jack was mortified to think that he had forgotten me and that he was going to have to face a five-star general as a second lieutenant. Of course, General Eisenhower kept up with Army football so he knew whom Jack was. General Eisenhower said, ‘Well son, are you planning on marrying this girl?’ Jack said, ‘Yes sir.’ Then General Eisenhower said, ‘Then you better start planning on taking care of her.'”

The game ended in a 0-0 tie before 74,121 fans. The tie was the only blemish for both teams as the season ended. In the final rankings, Notre Dame was selected the national champion while Army was ranked second.

Green would eventually be sent back to West Point on temporary assignment as an assistant football coach for the Black Knights. Now married, Green knew that he wanted a future in coaching and serving as an assistant under Blaik would give the young cadet valuable experience.

Blaik played his college football at Miami (OH) (1915-17) and West Point (1918-19). He graduated from West Point in 1920. Blaik would be enshrined into the College Football Hall of Fame as a coach in 1964 after compiling a record of 166-48-14. He coached at Army from 1941-58. Blaik previously was a head coach at Dartmouth (1934-40).

“We never lived on the post at all,” Mrs. Green said. “We lived in a small town outside the post called Fort Montgomery and that was by choice. Jack did not want to live on the post so he didn’t have to deal with superior officers. He really wasn’t home very much. As an assistant coach he did a lot of recruiting. It was a very fun time for me. The athletic department had three big buses that would take the team down to New York on Friday afternoon when we played in the city.

“Then on Saturday, the coaches’ wives and the official party would get on another bus and we’d go down to New York. Soon after we got to the George Washington Bridge, we’d be picked up by a police motorcycle escort and a whole brigade of police cars with sirens and lights flashing would take us flying into the stadium. It was fun.

“The really memorable trip that we made was by train to Notre Dame. Marie Lombardi, Vince’s wife, and I shared a suite on the train. Vince (Lombardi was an Army coach from 1949-53) was not from my hometown in New Jersey, but he coached football and basketball at the catholic high school there. He also taught chemistry and Latin. Vince was very smart. He also had a law degree. Jack and Vince became close personal friends before he became ‘the’ Vince Lombardi.”

In 1951 a cheating scandal on the West Point campus gained national attention that would escalate to the dismissal of 23 football players (83 cadets total). Blaik’s son, Bob, was a quarterback for Army and one of the players forced to resign. When the scandal broke, Blaik called it a “catastrophe.”

The Academy’s non-tolerance policy was “A cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do.” The Greens lived through that ordeal that brought an embarrassment to West Point.

“I don’t know how they do things now at the Academy, but there were two regiments,” said Mrs. Green. “They all took exactly the same courses while earning the same engineering degree. Monday, Wednesday and Friday the first regiment would take their classes and on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturdays the second regiment would take the very same classes. Evidently some of the football players who had taken the test, told the answers to the other football players and cadets. It wasn’t just the football players involved.

“If you knew that somebody has cheated you must turn them in to the Honor Committee. The whole thing was blown completely out of proportion. The reason that happened is because of Carl Blaik. A lot of the people on the academic staff were very jealous of the power that Carl Blaik had. When General (Douglas) MacArthur, General Eisenhower and General (George) Marshall were calling him after a game, people were jealous.

“He just had a lot of say about what was going on at West Point. Football players were still going to class on Saturday before a game. They went to class until 11:00 in the morning and then they started playing football at 2:00 in the afternoon. A lot of people on the academic stripe felt that Colonel Blaik had too much power and they seized upon this cribbing scandal as a way to take him down two or three pegs.”

After Green’s eight-year obligation at West Point was complete he resigned from military life with the rank of Captain and continued his coaching career at Tulane University in New Orleans. Mrs. Green said they enjoyed living in New Orleans, but the high academic standards made it tough to find enough quality football players to win.

The Green’s next stop was in Gainesville to coach for Ray Graves and the University of Florida. Green was an assistant head coach while being the offensive coordinator one year and defensive coordinator the next. Mrs. Green has one memorable trip to Baton Rouge.

“The five coaches’ wives made every single away trip,” said Mrs. Green. “If we didn’t go as part of the official party then we drove. So once when we went to LSU, our vice-president Dr, Harry Philpot, came on the trip and he was going to sit in the LSU president’s box. It just so happened that the President of LSU at that time was General (Troy H) Middleton, who was an Academy graduate.

“Dr. Philpot was going to sit in Middleton’s box. His wife didn’t make the trip and he wanted one of the coaches’ wives to sit with him. Obviously nobody was going to volunteer to sit in the LSU box. It turned out that we had to draw straws. So guess who drew the short straw. I had to go over there and sit with them. I was trying to be very polite and represent the University of Florida very well and not do anything that would embarrass anybody.

“But when it was obvious that in the last five minutes of the game that we were going to win, I just couldn’t stand it another minute. I turned to General Middleton and said, ‘We are going to win this game, and I’ve just been sitting here being quiet.’ He said, ‘Yes Jeanne, you’ve been wonderful. Now you can just let go.'”

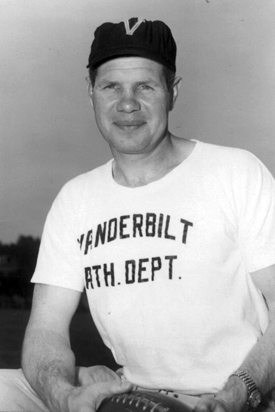

Art Guepe had been Vanderbilt’s head football coach for 10 years (1953-62) with a 39-54-7 record when he resigned after the 1962 season. The Commodores were coming off a 1-9 season. Over 60 applications to replace Guepe were processed.

After a screening reduced that number to 26, Vanderbilt’s Vice Chancellor Rob Roy Purdy, chairman of the Committee on Athletics, was still not pleased with the final selections. Green never applied for the vacant coaching position at Vanderbilt. The football coach would also have the title of Athletics Director.

“The reason that Jack didn’t apply for the job was that one of the other men on the Florida coaching staff had applied for the Vanderbilt job,” said Mrs. Green. “He didn’t feel it would be politically correct to also apply. Vanderbilt talked with a lot of people and didn’t want any of the people that they talked to. Mr. O.H. Ingram owned a barge company in New Orleans and he not only was on the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, but was also on the Tulane Board of Trust.

“He knew about Jack through the Tulane football team. Mr. Ingram suggested to the Vanderbilt Board of Trust that they call Jack and ask him if he would be interested in coming in for an interview. I said, ‘Jack, we don’t need to go to another private school. We’ve already done that. We are winning here so there’s no point in you going to Vanderbilt.’

“I guess he was just so intrigued that he was asked to come that he interviewed for the job. And it was a head-coaching job. Any worthy coach knows in his heart and mind that he can succeed where somebody else has failed. And if they don’t feel that way, they don’t need to be coaching anything. They did offer him the job.”

Green’s first season began with a rocky start as Furman upset the Commodores, 14-13 in the opening game in Nashville. The Commodores would finish that 1963 season 1-7- with its lone victory over George Washington, 31-0.

Green’s first season began with a rocky start as Furman upset the Commodores, 14-13 in the opening game in Nashville. The Commodores would finish that 1963 season 1-7- with its lone victory over George Washington, 31-0.

The day before GW game President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Vanderbilt did tie Kentucky (0-0) and Tulane (10-10) that season, but lost to Tennessee 14-0.

“Vanderbilt took about 10 years off his life,” Mrs. Green said. “It absolutely sucked the life right out of him. It was just horrible to watch. Jack never had a contract at Vanderbilt. He and Dr. Purdy would have an agreement and they would shake hands. He never had a contract because he said he would know when it was time to leave before anybody else did.

“When he had given it his very best for four years, and realized that he could not do any better than he had done, he resigned. There are photos of Jack smiling and happy to have the job and then four years later some photographer took a photo of him in the dressing room. It was a photo of him in just absolute utter despair. People actually wrote letters to the editor complaining how awful it was that somebody would print a picture of him like that.

“Football is not a job, it is a way of life. Everything in your family revolves around that job. It was just a lot of very hard work. You see these coaches today playing golf and having a great time, and Jack didn’t have time for any of that. Many of the Vanderbilt alumni, who were former football players, wanted Jack to go out and play golf with them. He said, ‘I didn’t come here to play golf. I came here to work.’ Jack did the best he could with it, and it just didn’t work out.”

Green’s four-year record at Vanderbilt was 7-29-4. His best season was in 1964 at 3-7-1 with a 7-0 upset win over Tennessee at Vanderbilt. In his final two seasons the Commodores were 2-7-1 and 1-9. In the SEC, Green was 2-20-2.

Green did make improvements on defense where the 1965 Vanderbilt defense was ranked No. 5 in the nation and No.1 in the SEC. Vanderbilt’s 1966 schedule was rated as the toughest in the country. Green’s commitment to Vanderbilt was revealed when during his tenure this time he was offered a chance at the head coaching position at the University of Oklahoma, a national powerhouse.

“I read about that in the newspaper,” said Mrs. Green. “I opened the newspaper and saw that article so I phoned him at the office. I asked what is this I am reading in the newspaper? One of Oklahoma’s U.S. Senator’s had died leaving that Senate seat open. Bud Wilkinson resigned his job as the Oklahoma coach (1963) to run for the Senate. So Oklahoma needed to find another coach.

“They called Jack about becoming their new coach. He told them he appreciated them calling, but he had a job and it was not the time of year for him to be leaving Vanderbilt. I know the reason he didn’t tell me about it because if he knew I had known about it, I would have had the moving van in our driveway before he could bat an eyelash. Jack was a man of such integrity. His reputation meant more to him than anything. I always said to him if he had to cheat to win he would have given it up.

“Jack didn’t have a contract at Vanderbilt. He could have easily just told Dr. Purdy, ‘I know we shook hands, but I’ve had a better offer.’ But he would have no more do that than cut off his hand. He honored his commitment. He said he had a job and never thought anything more about it.”

A few of Green’s top players at Vanderbilt were All-American Chip Healy; All-SEC players Gary Hart, Dave Malone, Lane Wolbe and Dick Lemay, Bill Juday, Dave Maddux and Sam Sullins.

In Green’s last season in 1966, the Commodores were 1-9 (SEC, 0-6). After a season-opening win over The Citadel, Vanderbilt lost nine straight including the final game in Nashville against the Vols, 28-0.

“Jack was just so beaten into the ground that he was really in utter despair,” said Mrs. Green. “We had the nicest kids. They just weren’t good enough to win in the Southeastern Conference. I knew a couple of days ahead of time that he was going to resign. Obviously, I didn’t say anything to anybody. The one saving grace was (Tennessean sports writer) John Bibb.

“It is such a shame that sports writers today don’t try to emulate him. Jack could talk to John and tell him something in confidence and know that it would never be repeated. There are probably not very many coaches in the country today that can say that. But when John had to write something bad, he always did it in the nicest way. John knew that it was going to happen.”

Roger May played quarterback for Green at Vanderbilt and graduated in 1968. He was attracted to the university by its academics reputation and having a chance to play early. May was recruited out of Pensacola, Florida.

“Coach Green was a very charismatic guy based on the fact that he was an All-American at Army,” said May, a Nashville attorney. “He was a great guy to be around and no nonsense guy. He tried his hardest within his limited capacity that the university gave him to produce a winner.

“Coach Green rarely got visibly mad. Sometimes he would overrule a coach or take part in something unless he thought it was absolutely necessary. If he opened his mouth, when he was watching you, then somebody screwed up. Coach Green had more of a calm demeanor. He never mentioned his time playing at Army or his own career, but everybody knew it. It was always what we needed to do to get better, and what we needed to do to win that week. He was never that type of guy that shared his feelings.”

After leaving Vanderbilt, Green stayed in coaching and was off to Kansas to be an assistant under Pepper Rodgers. Green was later lured to Baylor University during a time their head coach was on the hot seat of losing his job. Green went to Baylor with the premise that he would become the next Baylor head coach, but the Board of Trust would not hire an assistant from that present staff.

“That was the end of football for us,” Mrs. Green said about the Baylor situation. “Jack thought if that is the way everybody is going to play this game, he couldn’t deal with it any more. We moved back to Nashville because Jack was offered a job at Avco. When you’ve got three children with one in college and one getting ready to go, you go to where the job is.”

The Greens had three children David, Nancy and Dan. Green let his boys know that they were not expected to play football just because their father was a football coach. It was not always enjoyable being in a football family especially when things were not going well.

“I loved being a coach’s wife,” Mrs. Green said. “Anytime you lose, it is difficult. It got to the point at Vanderbilt where there was nothing to say when a game was over. Our children would suffer in that kids at school would say nasty things about their father. At Vanderbilt games, all the kids used to sit in the bleachers under the scoreboard. Some kid sitting behind our daughter made some really nasty remarks about her father and she turned around and knocked him right out of the stands.

“When we met at the car she told me what she had done. I said, ‘well good for you.’ I’ve wanted to do the same thing many times myself. We moved into another house in Nashville and the moving van was in the driveway. I saw this woman coming across the yard, and I thought this is one of the neighbors coming to welcome us. She looked at me and said I guess you know that it was my son that your daughter knocked out of the stands at the Vanderbilt football game. I told her I wasn’t aware it was her son. If it was your son, who are you? She didn’t even tell me her name and she went on and on.

“I said well if the situation had been reversed and somebody had something really nasty about one of your children about their father what do you think they would have done? That was probably the only time in her life that she didn’t have something to say. She said her son had a perfect right to say that because he bought his football ticket. It was hard on our children, but a lot of jobs are hard on kids.”

Green died in August 1981 of an illness at age 57. Bibb wrote in his column this tribute after Green’s passing:

“On a day like today, all the deceit and selfishness that so often cloud the broad scene of the world of sports seem insignificant to many of us. For that matter, the fun and good times that go with this business aren’t very important right now, either. That’s because there is a very special hurt this morning. Jack Green died yesterday.

“The special hurt so many people across the nation feel today is because Green was a special person, particularly special to those fortunate enough to have known him on a daily work basis. Special in deed, to those who watched him struggle with the Vanderbilt football program at a time when the odds against him succeeding were so heavy that surely only Green, and his players, recruited throughout the country, felt they could be overcome.”

Green would be enshrined into the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1989. He is also a member of the Hall of Fames at West Point and Tulane. It was not at West Point that Green’s character and integrity was shaped.

“That was instilled in him when he was a young child.” said Mrs. Green. “Jack had nine brothers and sisters. He was the fourth of 10 children. Jack was the one that the family could always rely on when anything was needed. He was the star pupil. He took every course they had in Shelbyville High School and never made anything less than an ‘A.’ Everybody thought he was the most perfect person they’d ever known.”

If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com