Dec. 10, 2014

Commodore History Corner Archive

One disastrous basketball game in the 1947 Southeastern Conference Tournament can be credited in contributing to the construction of Vanderbilt’s Memorial Gymnasium. Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky Wildcats had eliminated the Commodores from the tournament with an embarrassing 98-29 defeat.

Attending that game was Red Sanders, the Vandy athletics director and head football coach. Kentucky’s win sent a wake-up call to Vanderbilt basketball. Sanders would hire the school’s first full-time basketball coach, Georgia Tech assistant Bob Polk (1948-58, 1960-61). Nashville West End High School basketball standout, Billy Joe Adcock, was given the basketball program’s first scholarship in 1947.

Adcock became Vanderbilt’s first all-American and first player to score over 1,000 points. Polk’s first scholarship class of Jack Heldman, Dave Kardokus, Gene Southwood, George McChesney and Bob Smith played for three seasons (1950-52). Kardokus would become First Team All-SEC as a senior and led the Commodores to a championship victory over Kentucky in the 1951 SEC Tournament. Heldman logged the most minutes played. Now, the final ingredient necessary to be competitive in the SEC was a spacious gym to play its home games.

Vanderbilt had been playing its home games at the Hippodrome (an ice skating rink), area high schools, the Navy Classification Center located on Thompson Lane and later at David Lipscomb College. Practices were held at the Old Gym located on the campus and built in the 1870s.

The university’s Board of Trust formed a committee to seek the funds necessary to build a new campus gymnasium. It wouldn’t be until 1950 that the actual construction of the project began. The master architect, Edwin Keeble, was commissioned to build a combination gymnasium and concert hall.

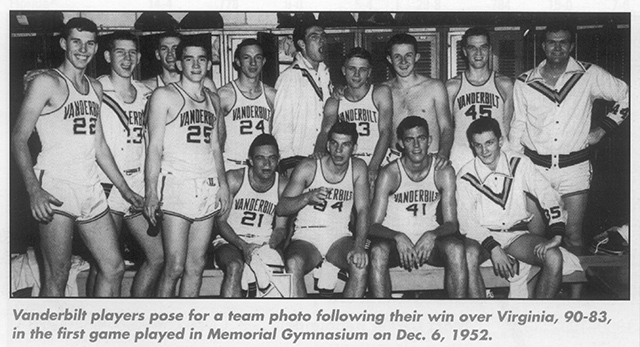

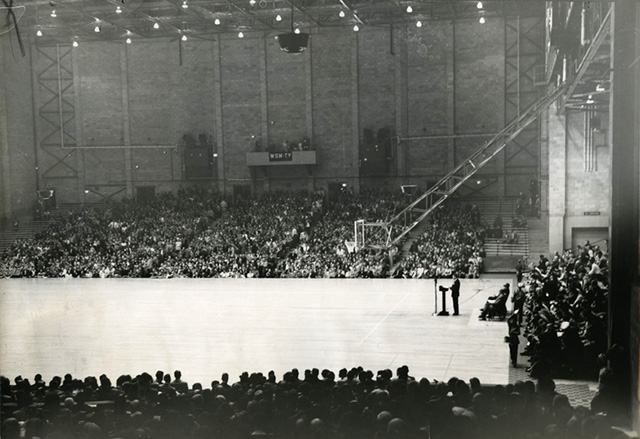

The plans called for a seating capacity of 6,583 at a cost of nearly $1.5 million. The gymnasium was ready for the team’s fall practice in 1952. Memorial Gymnasium was named in honor of the 144 former Vanderbilt students, men and women, who lost their lives in World War II. The dedication game was played on Dec. 6, 1952 against the University of Virginia.

The pre-game dedication program was presided by Vanderbilt Vice Chancellor C. M. Sarratt. Charles S. Ragland, who was the general chairman of the Memorial Gym fundraising campaign, presented the keys of the gymnasium to Vanderbilt Chancellor Harvie Branscomb. A memorial address was given by James G. Stahlman, publisher of the Nashville Banner, who served as chairman of the gymnasium committee of the Board of Trust. Dr. John K. Benton, Dean of the Vanderbilt School of Religion, gave the dedication prayer. The program ended with the singing of the National Anthem.

These are Stahlman’s remarks:

“Fifty-one years ago, I first knew Vanderbilt. As a spindly-legged boy of eight, in what was then worn and known as `short pants,’ I saw my first Vanderbilt-Sewanee football game. That same fall I first laid eyes upon the old gymnasium on the campus. Since that snowy day I have been deathly allergic, architecturally, to what I have sometimes facetiously referred to as `early Methodist Gothic,’ the most horrible example of which is that outdated, dilapidated temple of physical culture at the Twenty-Third Avenue gate. I revolted at the sight of it then. I do today.

“This great structure which we dedicate tonight, paradoxically, is the outgrowth of that allergy. When World War II was ended, it was apparent that Vanderbilt University should erect as appropriate memorial to those sons and daughters of the Commodore who had worn the uniform of their country in that war. Vanderbilt, in the opinion of some, knew no greater physical need for a new gymnasium. And so it was that this memorial was conceived in, proposed to and approved by the Board of Trust. It was the generosity of that board, so quickly and unhesitatingly expressed, in its first appropriation of a half-million dollars, which made certain the campaign for funds from alumni and friends of Vanderbilt, which have gone into this massive building.

“It has been the feeling that this gymnasium should be not simply a memorial to Vanderbilt men and women of World War II, the living and the dead, but it should be a constantly used facility for the development of strong, clean, active minds. It should be the training ground for keen competition, wholesome recreation, and true sportsmanship. It should be the undefiled shrine of untainted amateur athletics. It should be the revered monument to those who gave their lives for all Vanderbilt holds essential in human character, fundamental in our national institutions and sacred in our relationships with Him whose generous bounty makes this and all else both possible and worthwhile.

“Let this gymnasium and all which may ever take place herein befit the service of these men and women and especially the memory of those 144 who gave their lives for God and Country.

“Listen in reverence, with prayer upon your lips and gratitude in your hearts, as I read their hallowed names.”

Stahlman continued by reading the names of the 144 that died in service and concluded with “To the Glory of God and their memory we dedicate this gymnasium.”

Vanderbilt won the game 90-83. Dan Finch scored the first points in the gym, making two free throws only 11 seconds into the game. Moments later he made a lay-up for the gym’s first field goal. George Nordhaus scored a team-high 18 points in the game.

“I was our high scorer that night, but I will tell you it didn’t happen all that often,” Nordhaus said in an interview several years ago. “I’m sure proud of that one. Looking back on that, we kidded a lot about who would get the first points in the gym. Dan (Finch) was our best player, no question about that. I just happened to score more that first game than he did.”

Nordhaus was a sophomore in this era when freshmen were eligible for varsity play. He was an all-state basketball player out of Evansville, Ind., from where Polk lured him to Nashville with a scholarship.

“When I was being recruited, I knew that Memorial Gym was being built and that helped in recruiting,” said Nordhaus. “Of course, there was a great deal of excitement with the sellout crowd and everything. We were so up and it was such a thrill to be in there for the first game. We were just like little kids. I don’t think that we thought we were going to lose that game in any way, shape or form.”

That 1952-53 Commodore team rolled up a 10-2 record at Memorial, but just 10-9 overall (5-8, SEC). All their wins came in their new permanent home.

“We were terrible on the road,” Nordhaus said. “We really didn’t understand if it was home cooking or the excitement of the new place. In those days when we went to Mississippi or Mississippi State you were playing in a miserable place. It was hard to go down there and win in any of those places. It was so rabid you couldn’t hear yourself think. They were real small places with guys leaning over the top. Eventually they all got big gyms. Except for Kentucky, I don’t remember any good gyms at all.”

Scoring totals for the first game include: Nordhaus 18, Finch 13, Bill Feix 12, Tom MacKenzie 12, Jim Cummings 10, William Riley 8, Clarence Taylor 8, Bob White 7, Jerry Fridrich 2, Charles Buechlein 0, Dewey Thomas 0, Charles Harrison 0, Billie Gee 0, Ralph Schulman 0 and Thomas Grossman 0.

In that inaugural season in Memorial Gym, the Commodores defeated Virginia, David Lipscomb, Texas, Baylor, Yale, Georgia Tech, Florida, Georgia and Tennessee twice. The1952-53 squad recorded two Memorial Gym team records that still exist today.

After the Virginia game, David Lipscomb College made an appearance in Memorial Gym and loss, 92-66. The Commodores launched 120 shots from the floor against the Bisons. Later, against Yale, Vandy attempted a record 59 free throws.

Legendary sports writer Fred Russell wrote before the game in his Nashville Banner “Sidelines” column, “First-nighters at the gym will observe, among other features, the very latest thing in basketball goals. With hinges on the back side, and lifting into the ceiling when not in use, they are the only backboards of their type in the world.”

There is a plaque hanging on a wall in Memorial Gym by the entrance across Kensington Garage on the 25th Avenue South side that names all 144 men and women killed in World War II.

Memorial Gym has gone through many additions and renovations, which have brought the current capacity to 14,316. With its sometimes-improbable underdog victories, sell-out crowds, last second winning miracle shots and defeating No. 1 ranked visiting teams, the old friend made a name for itself as “Memorial Magic.”

The photos above are of James G. Stahlman giving his Memorial Gym dedication speech and looking at the plaque listing all the 144 Vanderbilt students killed in World War II. (From left to right): Ragland, Stahlman, Sarratt and Branscomb.

Traughber’s Tidbit: You can see a DVD of the pre-game dedication and part of the game action on YouTube, courtesy of Chip Fridrich, son of the late Jerry Fridrich. WATCH

Tidbit Two: The Vanderbilt men’s team has never recorded a losing season in the 62-year history of Memorial Gym. Their all-time record entering the 2014-15 season is 743-209 on their home floor (78 percent). Undefeated seasons include 1955-56 (13-0), 1960-61 (13-0), 1964-65 (14-0), 1966-67 (14-0), 1992-93 (14-0) and 2007-08 (19-0). The Vanderbilt women’s team began playing in 1977-78 and are 438-101 all-time (81 percent). They have only one losing season (5-6) in the 1982-83 campaign, but have had several one-loss years.

If you have any comments or suggestions contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.