Feb. 6, 2014

Commodore History Corner Archive

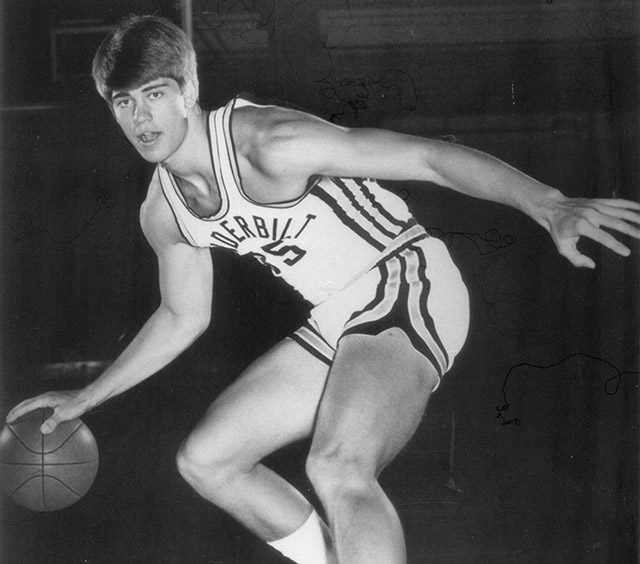

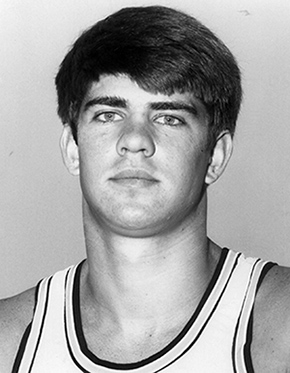

Former Vanderbilt basketball player Rod Freeman (1971-73) is the only Commodore to be drafted by the NFL, NBA and ABA. The New York Giants (seventh round), Philadelphia 76ers (11th round) and Memphis Tams (eighth round) selected him in 1973. Freeman might have been drafted a fourth time. A high lottery number prevented Freeman from being drafted again this time by the U.S. Army for the Vietnam War.

“I actually signed for more money in football than I did in basketball,” Freeman said recently. “I negotiated the contract myself. I was able to work a contact where I would avoid waivers. I had been offered a contract in basketball, but had not signed anything with Philadelphia. I thought I would get more money out of basketball, but that didn’t work.

“I got a signing bonus from the Giants and was to get another bonus if I made the opening day roster. They were going to a two-tight end set that year. I weighed about 225 pounds and the other players were much bigger. We were in pads one day and I thought to myself that I really wanted to play basketball. That if I didn’t buckle down and concentrate and play football I’m either going to get hurt or get somebody else hurt. I went to the coach at the time, who was Alex Webster.

“I told him they had been great to me, but my heart wants to play basketball. I’m from Indiana and that’s what I’m going to do. In my dorm room Webster and the team owner, Wellington Mara, came by to talk me into staying. I felt guilty about it so I gave back the bonus money. I didn’t have any strings attached. I thanked them and walked out of camp and to Philadelphia.”

Freeman, 63, is from Anderson, Ind., where his father was a swim coach. He was an outstanding athlete with chances to play in college on a basketball or football scholarship. But Freeman did not receive any college recruiting letters until after his junior year. They had been sent to him, but held back.

“Throughout my junior year some of the better players on opposing teams would ask me ‘Who you’ve heard from? Who have you talked to?’ And I would tell them, ‘I hadn’t heard from anybody,'” said Freeman. “I thought I was a good enough player to be hearing from colleges. After the tournaments in my junior year my dad handed me this box the size of two suitcases. It was full of letters. He and my high school coach thought it was in my best interest not to be bothered by all the recruiting attention.

“My father was grabbing all the letters coming to my house and my coach was grabbing all the letters going to the school. I wasn’t really excited about that. They thought they were doing the right thing and didn’t want me to be distracted. I grabbed that box and took it to my room. I took out the letters one at a time. I also played football so I had football letters also.

“One of the letters was from Vanderbilt. In the beginning of my junior year they were ranked 13th in the nation (in the) preseason. I thought I wanted to go to a school with good basketball in a good conference and good academically. I had interest from Duke, North Carolina State, Davidson, Purdue, Indiana and New Mexico. I went to New Mexico, to be honest, just for the trip. Coaches came to visit me. My high school basketball coach, Ray Estes, was going to Vanderbilt. I don’t know if he followed me to Vanderbilt or I followed him, but in the end I went to Vanderbilt.”

The SEC played a full freshman schedule usually as a preliminary game before the varsity. Freshmen were ineligible for varsity play at this time. One special varsity senior for Vanderbilt was Perry Wallace. Wallace broke the color barrier in 1968 becoming the first black basketball player in the SEC.

“Perry Wallace could not have been nicer to Rod Freeman,” said Freeman. “I kid people and tell them I’ve got my retired number hanging in the rafters of Memorial Gym. Perry was No. 25 and when I was a sophomore that was the number they handed to me. I started out in engineering and that’s where Perry was. I loved him to death.

“About the black-white issue, I grew up playing ball with black guys so to me they were brothers. I went to their house and they came to my house in high school. When I came to Nashville it was very different. On our freshman team we had one black player and he was a walk-on. As we traveled throughout the conference it was it interesting to see how blacks were treated. I wasn’t involved with it, but was I was aware of it. We didn’t have those issues in Indiana.”

Freeman was excited about playing basketball for Coach Roy Skinner and the Commodores. Unfortunately after playing freshman games in the preseason with Belmont, David Lipscomb and Trevecca, Freeman had an emergency appendectomy that slowed his progress.

Freeman was excited about playing basketball for Coach Roy Skinner and the Commodores. Unfortunately after playing freshman games in the preseason with Belmont, David Lipscomb and Trevecca, Freeman had an emergency appendectomy that slowed his progress.

“I went into the hospital on a Wednesday and came out of the hospital the following Wednesday and weighed 190 pounds,” Freeman said. “I lost 30 pounds in a week. I tried to get back to class and couldn’t do it. I went home for the Christmas holidays and came back to school in January. It took me a while to get my stamina and strength built up. I had a lot of infection in my body. My only memories from that year were those preseason games. We had four scholarship players and just two of us went through the entire four years and that was Ray Maddux and I.

“We played a game at Florida and were staying in a hotel by the interstate. Since my dad was a swim coach I loved to swim and the water. I was having a great time before the game jumping in the swimming pool. Ron Bargatze was my freshman coach. He came out and started yelling at me to get back into my room and rest before the ball game. Being in Florida in the wintertime was pretty cool.”

In Freeman’s first varsity season as a sophomore the Commodores were 13-13. At 6-foot-8 Freeman earned a starting position as a forward.

“My sophomore year was really the only time I played the entire year,” Freeman said. “I was a starter at one forward while Thorpe Weber was the other forward. Van Oliver was the starting center while Rudy Thacker and Ralph Mayes were guards. I was playing with four seniors. That team was probably the most talented team I’d been on. We were tall, fast, quick and could shoot the ball. The one thing that we didn’t have was chemistry. Coach Skinner was having family problems and we felt that on the floor in practice. On the floor my freshman year we would start five high school All-Americans. It was an unbelievable team.”

During that 1970-71 season Vanderbilt played Ole Miss in Memorial Gym. It was a shootout with Vanderbilt winning 130-112, the most points scored by a Commodore team. Freeman scored 16 points in that game.

In Freeman’s junior season the Commodores were 16-10 with more bad luck coming his way.

“At the beginning of the season I broke my foot and I didn’t really get going until conference time,” said Freeman. “It takes a while to get into a groove and playing shape. You can only get in playing shape when you are running up and down the court when the whistle is blowing. We did get this new crop of guys like the F-Troop [Joe Ford, Lee Fowler and Butch Feher] and the situation with Coach Skinner was still going on.

“We didn’t know at the time about his problems until much later. Jan van Breda Kolff, Terry [Compton], Bill Ligon, and Lee Fowler were really good ball players and were sophomores that year. We had the makings of a good team then, but still lacked the chemistry.

“You look at our record my senior year [20-6] versus the way we were the first two varsity years. Coach Skinner and his wife got a divorce during the summer of my junior year. It was like his mind was free. All of a sudden he began to coach and interact more with us whereas before he was more reserved. I never understood that when it was going on. My junior year we did not play together as a team at all. All those seniors that started the year before had left. I didn’t start because I was sitting on the bench the first part of the season nursing a bad foot. So all five starters were gone.”

Freeman played on a team his senior year that went 20-6 (13-5 SEC) and tied for second in the conference. He was still slowed by old injuries, but played on a team that put it all together.

“In the beginning of my senior year every one of us knew what our jobs were,” Freeman said. “We were not individuals, but more like a team. I knew I needed to get in there and rebound. When I was asked to score I was expected to score. I was expected to play defense on the inside guys. If anyone of us got hurt or took a rest on the bench somebody else would step up and play. On my senior year team I had never seen so much chemistry with as good as it was.

“We knew when we went into a game we were going to win that ball game. We knew it. I had never been on a team like that before and that is an unbelievable feeling as a player. We started the season 8-0. We’d played some nationally ranked teams and were ranked 11th in the nation. It hurt me that I had broken my foot and couldn’t play much anymore.

“I hoped that my teammates missed me as much as I missed them. Coach Skinner was fantastic that year. Had it been like it is now we would have easily gone to the tournament that year. They were even better the next year winning the SEC championship. Of course, they got rid of the dead weight with me and Ray Maddux (laughing).”

One of Freeman’s teammates was Steve Turner. Turner was 7-foot-4 and ranked as the No. 1 high school recruit by some experts. Turner was one year ahead of Freeman, but took a redshirt after his junior year and graduated with Freeman’s class.

“Steve was a friend,” said Freeman. “If you are 7-foot-4 and had to put up with some of the comments back then about you, some good and bad, you’d probably be different yourself. Steve went to Bartlett High School in Memphis. His basketball coach was actually the head football coach. I suspect Steve did not get a lot of instruction on playing basketball as a high school player. When he came to Vanderbilt he was relatively raw. To be honest he probably didn’t get a lot of instruction when he came to Vanderbilt.

“Coach Skinner was able to recruit guys that already knew how to play basketball. Steve didn’t know how to play basketball as well as some of the other guys. But what he could do at 7-foot-4 was dunk the ball when he got inside. The NCAA changed the rules. You couldn’t dunk the ball after Lew Alcindor [Kareem Abdul-Jabbar] dominated with his height. Now Steve has to lay the ball up and use more finesse on the inside. More than he had to in high school.

“In high school he is 7-foot-4. How many high school guys are going to stop him? In college he had more competition, bigger and better players and he couldn’t dunk the ball. I would walk in airports with him and people would make fun of how tall he was. He was an 18-, 19-year-old kid and would have to be mature to handle that. He didn’t always handle that very well.”

Eventually selected by the New York Giants in the NFL draft, Freeman was expecting to be chosen by Tom Landry’s Dallas Cowboys. He dressed and worked out in Vanderbilt’s spring football practices.

“Gil Brandt of the Dallas Cowboys met with me after a Vanderbilt basketball practice,” Freeman said. “The Cowboys had some type of computer system that showed I had good size and good hands as a basketball player. And I had football scholarship offers after high school. When I should have been studying I was in my dorm room taking all these psychological tests for Dallas. On draft day the New York Giants selected me, which was a surprise. I had only talked to Dallas.”

With his love for basketball, Freeman was hoping he’d be chosen in the NBA draft. Philadelphia chose him in the 11th round.

“Being a kid from Indiana I was hoping I’d go in the first round,” Freeman said with a laugh. “I didn’t have much to lean on and I had been injured a lot. I didn’t get much feelers in basketball. I was drafted in the 11th round, which back then was called the supplemental rounds.

“The guy that helped me prepare to play at the next level was Ed Martin over at Tennessee State University. I would go over there and work with him in the summer. He had a relationship with the general manager in Philadelphia. If I had a guess he might have asked that Philadelphia at least take a look at me. So they probably wasted their 11th round choice on a guy named Rod Freeman.”

In the 1973-74 Philadelphia season, Freeman played for a poor team that secured a 25-77 record. Gene Shue coached the 76ers. Freeman appeared in 35 games, scoring 106 points (3.0 average), making 39-for-103 shots (37.9 shooting percentage) along with 54 rebounds, 14 assists and one blocked shot.

“It was the first time in my life I dealt with sitting on the bench when I wasn’t injured,” said Freeman. “The year before, Philadelphia had the worse record in NBA history [9-73]. They actually cleaned house, which is one reason I was able to secure a roster spot. Oddly enough, I played all through preseason and started. In rookie camp I led the team in scoring and rebounding in the first game. Doug Collins and I shared scoring honors in the second game.

“I started all the exhibition season at forward. The first game of the season we played Houston at the [Philadelphia] Spectrum and I found myself on the bench. I didn’t start. I couldn’t understand that. I thought I’m a rookie and I’m not supposed to start. I ended up playing a few minutes at the end of that game. I didn’t play again for 15 games. The experience that I had was phenomenal though. I met a lot of great people. I played against some guys I watched playing professionally when I was a kid.

In this era of NBA basketball the top players included Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Walt Frazier, Rick Berry, Elvin Hayes and John Havlicek. The ABA was still in existence, but declining with financial difficulties. The league shut down a couple of years later.

“A lot of the really good ABA players were coming back to the NBA,” Freeman said. “The NBA teams had secured their draft rights early on and had access to those guys. In Philadelphia, Billy Cunningham came back to the 76ers. This was the era that I was in. The first time I had a chance to play in Madison Square Garden we were switching off on guys. All of a sudden I found myself at the top of the key guarding Walt Frazier. I thought what is Rod Freeman doing guarding Walt Frazier in the Garden? This was a guy I grew up watching. Abdul-Jabbar was in Milwaukee.

“I helped hold Rick Berry to 52 points one night. Had I gone in to guard him, no telling how many points he might have scored [laughing]. This actually happened when we played Golden State at their place in Oakland. (Former Vanderbilt All-American) Clyde Lee played for the Warriors then and could not have been nicer to me before the game when we had a chance to visit. I will always remember his encouragement and kindness to me.”

“Tom Van Arsdale was a guy I got to play with. The Van Arsdale twins were great athletes and from Indiana. Every kid growing up in Indiana wanted to be like Tom or Dick Van Arsdale. I was walking out on the floor during the first day of veterans’ camp in Philadelphia and there is Tom Van Arsdale. I introduced myself to him and told him it was a privilege for me to play ball with him out here. He was 6-foot-4 and I was 6-foot-8 and I looked up to him.”

Lee would join the 76ers the next year when Freeman left Philadelphia. That rookie season for Freeman would be his last as a professional basketball player.

“Coach Shue wanted me to go to Los Angeles and play in the summer league,” he said. “I had spent all the money I saved during my rookie season. I came back to Nashville and went to work. I played basketball at TSU and Fisk all summer long. As the result of not having a no-cut contract they let me go. They released me in September not long into training camp. It was really the first time in my life I experienced rejection. I thought I’d go home and start to earn an honest living. The rest is history and I have no regrets.”

Freeman worked at First American National Bank, managed a construction supply company and served as Vice President of Marketing for Murray Ohio Manufacturing Company. In 1985, he founded Fitness Systems, Inc., and sold it in 1998. He is currently President of Rocking R Companies, LLC that he founded in 2001. In 2011, Freeman was elected to a four-year term in as Brentwood (Tenn.) City Commissioner.

Traughber’s Tidbit: Carl “Zeke” Martin was a Vanderbilt basketball player/coach for the 1910-11 and 1911-12 seasons. He was a Mobile, Ala. native and arranged a game between his Commodores and the Mobile YMCA team in his first season. Martin decided to stay a few extra days in Mobile to get some rays on the sandy beaches with his team. Vanderbilt officials were so upset over this unauthorized “vacation” that Martin was suspended for the rest of that season.

Martin was by trade a mechanical engineer and an avid fisherman, sportsman and explorer that led to world travels. He developed a 1,000-acre section of a remote beach near Mobile as a vacation spot. The land was later subdivided and developed. In his honor six acres are named “Zeke’s Landing” which today is a marina with deep-sea fishing, restaurants and water sports.