April 13, 2016

Ralph Edwards and Grantland Rice are photographed with participates of “This is Your Life.”

Commodore History Corner Archive

“Grantland Rice. This is your life,” host Ralph Edwards said on the new NBC national radio program on December 28, 1948 from Radio City in Hollywood, Calif.

This Is Your Life began in 1948 and lasted on the radio until 1952 and continued on NBC television until 1961. The premise of the program was to surprise a guest (usually some type of celebrity or famous person) and take them through their life in front of an audience. Colleagues, family and friends made surprise special guest appearances. The Rice appearance was the program’s second show.

Rice was a legendary sports writer of national prominence that was born in Murfreesboro. Tenn., on November 1, 1880. While growing up in Nashville, Rice would prep at Wallace School. Rice would later describe the founder and headmaster, Clarence B. Wallace, as the most influential teacher he experienced. He would credit Wallace for his writing success due to the introduction and importance of Latin and Greek. Rice’s gift of his poetry was enhanced by these studies.

Rice found his way to Vanderbilt University in the fall of 1897. Football was a sport he cherished, but the three years on the Commodore gridiron only gave him painâ€â€literally. Used mostly as a substitute, this135-pound man accumulated a broken arm, four ribs torn from his spinal column, a broken collarbone and a broken shoulder blade.

Amazingly, his determination endured these hardships and he played four years of baseball where he became team captain. He claimed to have never missed a baseball practice and never missed a game after his freshman season. Rice’s most memorable game came against the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Playing first base, Rice contributed to a Vanderbilt 4-3 victory with 15 assists, no errors, a home run and a double.

Rice helped lead Vandy to the Southern Conference championship just before his graduation in the spring of 1901. He graduated with a B.A. degree in Greek and Latin. Rice graduated in the first Phi Beta Kappa class out of Vanderbilt.

Since Rice was successful in the arts while at Vanderbilt he saw an opportunity to pursue journalism. The Nashville Daily News was in its infancy, only a few weeks old when he applied for a job as a sports editor. To his amazement he got the job for five dollars a week. The legend was about to begin.

Rice would leave Nashville for writing jobs in Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Cleveland. He wasn’t comfortable in Cleveland and accepted a job as sports editor at a new newspaper in Nashvilleâ€â€The Nashville Tennessean. Eventually, Rice moved to New York City and became a legend in sports writing.

In 1908, the Vanderbilt baseball coach had to leave the team and Rice offered to coach for this one season. His team was .500 in what was termed a rebuilding year.

In 1948, the Dean of American Sports Writers had been wintering in California, a custom for him. Some friends from Vanderbilt and his longtime secretary, Catherine Mecca, and others, set up the surprise radio appearance by telling him Edwards wanted to interview him about the upcoming college football bowl games. Instead of being placed in a small radio booth, Rice was seated alone on a stage in front of an audience in a large room. This was 30 minutes before the afternoon program began.

From the 1999 book by William A. Harper How You Played the Game, The Life of Grantland Rice:

“Edwards came on stage. He began reviewing Rice’s birth in Murfreesboro in 1880, and his childhood there and in Nashville. Rice squirmed. Edwards asked him if he remembered anything about a cherry tree. Rice looked puzzled, squirmed some more, and drawled, ‘No. I don’t think so.’

“‘You didn’t cut one down?’

“‘No, that was somebody else.’

“‘Well, how about falling out of one?’ Something flashed in Rice’s mind. Then, a voice from behind the curtain: ‘Mama! Grant fell out of the cherry tree and I believe he’s broken his arm!’ Stepping out from behind the curtain was John, his brother, who he hadn’t seen in seven years.

“As the show moved along, Rice aged. His school days, and then the subject of his beloved teacher at Wallace School, C.B. Wallace came up. ‘Were you a good student!’ asked Edwards. Rice said he worked pretty hard, but that football and baseball took up much of his time.

“‘I wonder what Mr. Wallace thought of your efforts?’

“‘Not much, I suppose, but he taught me the rudiments of Latin and everything I know.’ Rice reached back through over a half a century and began to recite: ‘Arma virumque cano Troiae qui primus ab oris…‘ Just then, again from behind that curtain none other than Mr. Wallace himself uttered in a gentle Southern accent: ‘I never had to excoriate his epidermis.’ Rice practically fell off his chair. At eighty-nine, the chipper schoolmaster Wallace had flown out to California to surprise his old and famous student. Wallace stole the show, too, ad-libbing at will.

“As far as his own age, Wallace said that the only older objects he had noticed were a few eagles seen on the plane flight on his way to California. When Rice referred to a letter he recalled having written to Wallace a few years back in which he said that ‘if I had gained any measure of success in writing, I owe it all to you.’ The jocular Professor Wallace remarked: ‘Now right there’s the best piece of writing you ever did.'”

The show continued with more of Rice’s career reviewed. More friends of Rice were trotted out as were many of the All-American football players he named over the years including the famed Four Horsemen of Notre Dame (1924)– Harry Stuhldreher, Jimmy Crowley, Don Miller and Elmer Layden. A copy boy from Rice’s time in Atlanta made an appearance.

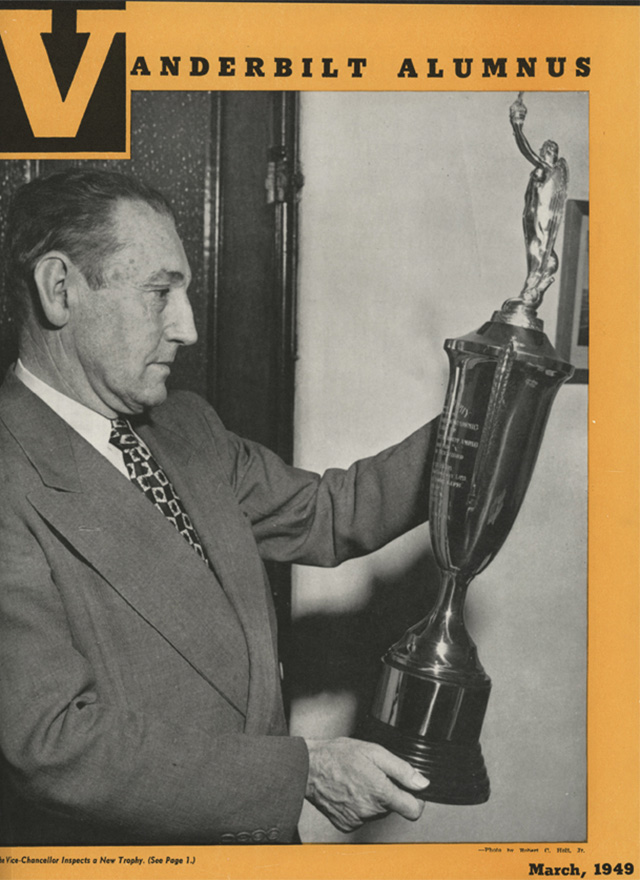

Jim Thorpe, whom Rice said was the greatest athlete of all time, also greeted Rice. The program ended with Amos Alonzo Stagg, a legendary football coach, who knew Rice from his days in Nashville. Stagg announced that “Philip Morris,” the sponsor of Edwards’ show had established a “Grantland Rice Trophy” at Vanderbilt to honor one of the university’s students who combined academic and athletic ability. The trophy was to remain on the Vanderbilt campus with each year’s winner’s name to be inscribed on it. The winner would be revealed at each Vanderbilt commencement.

After the broadcast there was a party for Rice at the Hollywood-Roosevelt Hotel with all the show’s participants and others. Of course, to learn about some of the behind the scenes information look to a Fred Russell Nashville Banner column. Russell, also a Vanderbilt alumnus, and Rice were close friends. Russell wrote after the event:

“Right here it should be stated that one of the top assists of the show should go to Vice-Chancellor C. M. Sarratt of Vanderbilt. When Edwards’s scriptwriters sought some Vanderbilt baseball or football teammates of Rice to appear on the program, it was Sarratt who suggested Professor Wallace.

“Professor Wallace was undecided about accepting the invitation. He telephoned me twice last week, both times ‘on the fence.’ When Jimmy Barbour, his nephew, said he would accompany him that fixed it.

“To be put into effect at once, the trophy, carrying Rice’s name, will be inscribed: ‘In honor of the men whose academic record for the year at Vanderbilt University was highest among athletes who earned the ‘V’, their names inscribed. It is a permanent trophy.

“The program, well prepared and well presented, was of calculable value to Vanderbilt. Jim Chadwick, chief writer for Ralph Edwards, telephoned from Santa Monica, Calif., exactly six times to Bob McGraw, assistant to Chancellor Harvie Branscomb, and received splendid cooperation, McGraw furnishing most of the program information and fulfilling each added request and new thought.

“Above all, though, was the quality of the subject. Grantland Rice is a thoroughbred, one of the real persons.”

Said Sarratt after the program aired, “I have not been officially notified as to how the trophy is to be handled. And I don’t know when we will get it. But I am delighted over it.”

Other engravings include: Grantland Rice Trophy For Achievement in Scholarship and Sports, Donated December 28, 1948 by the Philip Morris and Company LTD. Radio Program “This Is Your Life.” In Recognition of Grantland Rice, B.A., Vanderbilt University, 1901â€â€Baseball, 1899, 1900, 1901 (Captain)â€â€Football, 1899â€â€Phi Beta Kappa.”

So, where is the Vanderbilt Grantland Rice Trophy in 2016? The historic trophy now rests in a trophy case with other vintage Vanderbilt athletic trophies in a McGugin Center conference room. However, no Vanderbilt’s athlete’s names are inscribed on the trophy as originally intended.

That might be of foresight, as the slender trophy would carry a limited number of names in future decades. And the original engravings take up an entire portion of the trophy. A Vanderbilt student-athlete was honored at each commencement in Rice’s name.

In 1984, Russell’s name was added to the scholarship making it the Fred Russell-Grantland Rice Sports Writing Scholarship. The award is given to a student interested in pursuing a career in sports journalism.

Rice died in his New York City office on July 13, 1954 at age 73. He was working on a story about Willie Mays and the All-Star game. Upon Rice’s death another “Grantland Rice Trophy” was presented annually to the college national football champions recognized by the “Football Writers Association of America.”

A different Grantland Rice Trophy was presented from 1954-2013. That initial award was presented to ULCA in 1954. The Bruins were coached by former Vanderbilt football player and head coachâ€â€Red Sanders.

If you have any comments or suggestions contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.

Vanderbilt Vice-Chancellor C. M. Sarratt examines the Grantland Rice Trophy.