April 14, 2010

View Commodore History Corner Archive

View Commodore History Corner Archive

Purchase Traughber’s book Nashville Sports History

Grantland Rice was born in Murfreesboro, Tenn., on Nov. 1, 1880. He became a legend and a pioneer in sports writing journalism developing an art of language and poetry into the profession he dearly loved.

By the time he grew into a teenager, Rice was living in Nashville on Vaughn Pike. Later, the family moved into a larger house on Broad St. (now 10th Ave.), where he played games with the neighborhood kids.

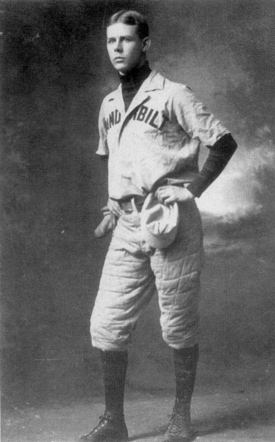

Rice found his way to Vanderbilt University in the fall of 1897. Football was a sport he cherished, but the three years on the Commodore gridiron only gave him pain–literally. Used mostly as a substitute, this 135-pound man accumulated a broken arm, four ribs torn from his spinal column, a broken collarbone and a broken shoulder blade.

Amazingly, his determination endured these hardships and he played four years of baseball where he became team captain. He claimed to have never missed a baseball practice and never missed a game after his freshman season. His most memorable game came against the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. He contributed to a Vanderbilt 4-3 victory with 15 assists, no errors, a home run and a double.

Rice helped lead the Commodores to the Southern Conference championship just before his graduation in the spring of 1901. Rice graduated with a B.A. degree in Greek and Latin. He graduated in the first Phi Beta Kappa class out of Vanderbilt.

Barnstorming for several weeks in the summer with a semi-pro baseball team gave him the confidence to consider playing professional baseball. However, his shoulder injury from football ruined that aspiration.

Since Rice was successful in the arts while at Vanderbilt he saw an opportunity to pursue journalism. The Nashville Daily News was in its infancy, only a few weeks old when he applied for a job as a sports editor. To his amazement he got the job for five dollars a week. The legend was about to begin.

Rice was blessed with the gift of writing rhythmic heads and verses for his leads. His managing editor complimented him on these stories, which in the beginning were printed without a by-line. One of the first poems to appear was in the Aug. 13, 1901, edition. After covering a baseball game between Southern Association members Nashville Vols and Selma at Nashville’s Athletic Park (later Sulphur Dell) he wrote:

Baker was an Easy Mark, Pounded Hard over Park,

Selma’s Infield is a Peach, But Nashville now is out of Reach,

All of the Boys Go out to Dine, And Some of them Get Full of Wine.

After their long, successful trip, the locals opened up against Selma yesterday afternoon at Athletic Park, and when the shades of night had settled on the land the difference that separated the two teams had been increased by some dozen points.

Throughout the whole morning a dark, lead-colored sky overhung the city, and a steady rain dripped and drizzled, only stopping in time to play the game, but leaving the field soft and slow.The reader would have to find the box score to learn the outcome of the game. The year 1901 was the inaugural baseball season of the Southern Association. The Nashville Vols franchise was in first place throughout the season and eventually won the first championship. The interest in Nashville was intense as baseball fever grew. The Nashville Daily News was an afternoon newspaper, which meant scores were always a day late. Rice would cover the Vols by train for key out-of-town games.

To beat the other newspapers in Nashville, Rice devised a plan to send detailed information back to Nashville for important games. He used a telegraph wire hook-up from the ballpark with recruited telegraphers to relay game information in a bulletin-type style.

For a small fee, crowds in the Masonic Theater or from two bowling alleys on North Cherry St. would receive detailed information just moments after a play was made. Some of these games were scripted as if the game was getting play-play action, which built suspense.

Rice would also give this advice for unruly fans that attended baseball games in Nashville:

When you’re sitting on the bleachers and your yelpings rend the sky,

As you watch the lissome base hit or the long summer and twisting fly,

Don’t forget your parlor manners, do not raise particular Ned,

And don’t saturate your neighbor with the pop that is red!

If you see a head below you, pool-ball like, devoid of hair,

Don’t hit it with your cushion–let it roost in calmness there–

And when evening comes in silence, and the sun sinks in the West,

Shake the peanut shells from off you, and go home to well-earned rest.Rice would leave Nashville for writing jobs in Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Cleveland. He wasn’t comfortable in Cleveland and accepted a job as sports editor at a new newspaper in Nashville–The Nashville Tennessean.

In 1908, the Vanderbilt baseball coach had to leave the team and Rice offered to coach for this one season. His team was .500 in what was termed a rebuilding year.

Rice moved on to the glamour of sports writing in New York City and died in his office on July 13, 1954. He was working on a story about Willie Mays and the All-Star game.

If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via email WLTraughber@aol.com.