Feb. 27, 2008

![]() Q &A with Charles Davis (pdf) | History Corner Archive

Q &A with Charles Davis (pdf) | History Corner Archive

|

|

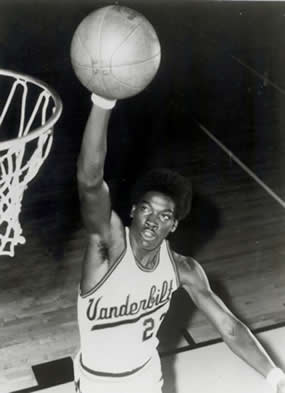

Charles Davis was a Vanderbilt basketball player (1977-81) who thrived to be the best he could in athletics and as a citizen. Growing up in South Nashville public housing, Davis desperately wanted to escape his environment of poverty, drugs and crime. Prior to arriving on the Vanderbilt campus, Davis won a state high school championship with McGavock as a senior and was named MVP. He earned a basketball scholarship to Vanderbilt and continued with an NBA career.

As a Commodore, the 6-foot-7, 215 pound Davis was a first, second or third team All-SEC player in his collegiate career that includes a red shirt year. Davis is currently ranked 8th on the all-time scoring ladder with 1, 675 points. For his career, Davis averaged 16.0 points per game with a 51.4 field goal percentage. His 683 career field goals are tied with Mike Rhodes for first. Davis led the Commodores in rebounding in each of the four years he played.

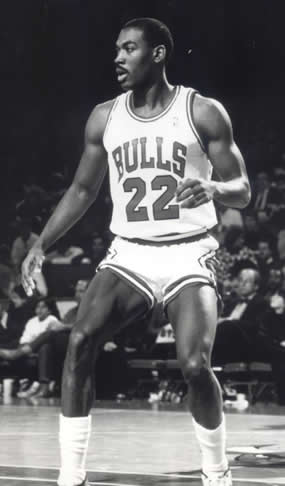

Davis was selected in the second round (35th overall) of the 1981 NBA draft by the Washington Bullets. In his eight years Davis played for Washington (1981-85), Milwaukee (1985-part of 1988), San Antonio (part of 1988) and Chicago (1988-90). Primarily coming off the bench, in 415 regular season career games Davis averaged 5.3 points per game, a 45.1 FG percentage (970-of-2152) and 2.4 rebounds a game. He also played overseas basketball in Japan. Davis currently runs the Charles Davis Foundation in Nashville.

Recently, Commodore History Corner researcher and writer Bill Traughber spoke with Charles Davis about his careers at Vanderbilt and in the NBA. This is their conversation:

Bill Traughber: When did you first gain a desire to become the best basketball player you could be?

Charles Davis: We were in a neighborhood program where we were taken to Vanderbilt to see a basketball game. I was 11 years old at the time. It seemed so far away from where we lived. The players were running up and down the court. People were cheering every time they scored a basket or did something good. They had uniforms on with their names on the back of their jersey. I was just in awe and thought this is where I want to come and play basketball. I wanted to know what I needed to do to become a basketball player at Vanderbilt. I just practiced and played against everybody that was better and supposed to be good. As I got older at 15 or 16, I wanted to play the best and challenge the best. Once I was able to realize I was a decent player, I was getting respect on the basketball court.

BT: Prior to your senior year, did you realize McGavock had a good enough of a team to make it to the state championship game?

Davis: In the beginning of my senior year, I told the home economics teacher I wanted her to make me a suit. She asked me why. I said we are going to win the state championship and I’m going to be MVP. She said she wouldn’t make a suit for me, but if I took her class, she’d show me how to make a suit. I took the class and at that time it wasn’t cool for boys to take home economics. I really needed that suit. I wasn’t the only boy in home economics, but it was like “Dude, you’re taking home ec?” We became very close. She was like my godmother. Her name was Betty Payne.

BT: McGavock did win the Class AAA state basketball championship in1976 and you were named MVP. What do best remember from that night?

Davis: We played in the state championship game and I was named the MVP. And there was Coach Ray Mears who was at Tennessee at the time. A few of us were outside in the parking lot sitting on a car talking about the game and waiting for the bus. Mears walked up to us and it was his car I was sitting on. I said I was sorry and Mears said it was all right that I could sit on his car or I could have it. Then he introduced himself. It was a funny moment.

BT: Besides Vanderbilt, what other colleges had an interest in giving you a basketball scholarship?

Davis: I was recruited all over the country, but I narrowed it down to Vanderbilt and Tennessee. At the time, Tennessee had Bernard King and Ernie Grunfield, which was the “Ernie and Bernie Show.” If I’d gone there, they would have been seniors while I was a freshman. Vanderbilt had the F-Troop a few years before and they didn’t really have a dominant player. So I thought it was wide open at Vanderbilt and I could be as good as I wanted to be from the start. I wanted to start and wanted a challenge. Vanderbilt was local and it was the right decision. I asked coach (Wayne) Dobbs if I could start and he told me if I was good enough, I could start. I asked him if I could have any number I wanted. He said if I was good enough, I could have any number I wanted. Ronnie Bargatze, who was one of the assistants there, was one of the reasons I came to Vanderbilt. I liked his personality and attitude. He was like a father figure.

BT: Richard Schmidt replaced Wayne Dobbs just before what would have been your senior year. You had to red shirt due to injuries. Was that a difficult time for you with a new coach and an injury?

Davis: We were playing at Mississippi State and Schmidt wanted to put me in hurt. I’m hobbling and limping around, but he put me in the game. I was in pain. I told him I couldn’t play. He said to go ahead anyway that he wanted me to play. I told him I’d try, but I’m on one leg. I went in running up and down the court. I’m still mad. I got the ball and dunked it as hard as I could. In the locker room at halftime I was in so much pain. I was in tears. Schmidt kicked a trashcan that almost hit me. He started yelling at me. I said, “Coach Schmidt, I’ve never disrespected any coach in my life. I’ve always done anything you’ve asked me to do. Joe Worden (Vanderbilt trainer) told you I can’t play and you’re trying to make me play. He had a tenacity to grab a player or punch them in the chest. I told him, `You’re not going to put your hands on me. My father doesn’t put his hands on me. I can’t play. I’m not going to play anymore. You can red shirt me after this game. I’m done.’

BT: You did red shirt. So during your senior year you and Mike Rhodes were named “Town and Country” which has become a part of Vanderbilt basketball history. Both you and Rhodes entered the season as seniors with a great chance to break Clyde Lee’s all-time scoring record. This was a controversial time for Commodore basketball as Schmidt mysteriously benched both you and Rhodes for much of the season. Rhodes did break the record in his last game in the SEC Tournament. Can you tell me what happened at the time?

Davis: During my senior year I needed about 86 points to be the all-time leading scorer at Vanderbilt. Rhodes and I would have gotten that in several games between the both of us since we were the one-two punch of “Town and Country.” For some reason, they didn’t want me to have the scoring record. Richard Schmidt wanted to play the players that he recruited. We had a good team. He came in with a Bobby Knight syndrome. He was going to coach the way he wanted to.

BT: Coach Schmidt would be fired soon after your last game. You were named to the Third Team All-SEC. And this is while you came off the bench in most games. You were still drafted in the second round by the Washington Bullets. Did playing for the Bullets help you end this emotional year in your life?

Davis: I went to camps and the NBA coaches were calling my college coach (Schmidt). He told them I couldn’t play. He’s not coachable. He doesn’t follow instructions. He can’t learn the plays. You don’t want to mess with this kid. He is a bad seed. I went to Washington and they had just won a championship a few years earlier. There were 65 guys in camp, and there are only two positions on the team. I was finally healthy with no injuries. I was working out hard and running. In three days of mini-camp, I was dunking over everybody and scoring. Bob Ferry, who was the general manager, pulled me off to the side. He said, `Charles, would you have a problem if we drafted you in the first round?’ I had my game face on. I didn’t want to smile. I said I didn’t have a problem with that. Then he asked me what was going on at Vanderbilt. They said that you’re not coachable; you’re not a team player. I said, “Mr. Ferry, let me tell you something. I came here for one reason. I came here to help Washington win a world championship. What you saw me do on the court the last few days, you take that and consider it. That’s the type of player I am. What my coach told you, go back and reassess that. Go back and tell him to be truthful to you. Ferry said we are going to take you in the first round. So after that I’m good. I went to Houston’s camp and there were a few other camps that they wanted me to go to. But I thought I wasn’t going to any other camps. The Bullets told me they’d draft me. When I was in Houston, they said they wanted to see if I could pass the ball to Moses Malone. I said I’m out of here.

BT: You were drafted in the second round. Frank Johnson of Wake Forest the first-round selection by the Bullets. What did the Bullets tell you?

Davis: I was mad. That was a difference in guaranteed money. I got a call from Washington and they said, `Charles, congratulations, we like you and look forward to you playing with us.’ I said, `What happened? You were supposed to take me in the first round.’ They said, `There was a move that came from upstairs that we needed a guard. But we are going to treat you like a first-rounder when you get here.’ They flew me up and there was a contract on the table with a one-year minimum. That’s what a second-rounder makes. I said, `Hold on. You said you’d treat me as a first-rounder. I’m totally upset.’ They said they weren’t really sure because of what happened at Vanderbilt and what happened to your coach. We just wanted to be sure. After your third year, you are going to jump up and make nice money. But it still was not a guarantee.

BT: Did you ever make big money in your NBA career?

Davis: In the eight years that I played in the NBA, I never had a guaranteed contract because of my situation at Vanderbilt. I did take the one-year, which was not guaranteed, but the minimum was $70,000. So I had to lock myself in for five years. In the third year my money was supposed to jump where I made some decent money. I played well in the summer league scoring 30-something points a game. It was like `Davis can play for the Washington Bullets, but he can’t play for Schmidt.’ This is still hanging over my head. When I got to my third year in my contract they said we decided to trade you. I got traded to Milwaukee. It starts over as far as money. It was minimum salary, which had gone up to $125,000. I should have been making $900,000 after my third year.

BT: The first NBA game you played was against Julius Irving–Doctor J. Were you intimidated with such a player?

Davis: I used to watch this guy play on TV. At that time you had playing for the 76ers Dr. J., Darryl Dawkins, Bobby Jones, Maurice Cheeks and Andrew Toney. I’m a pro now. I’m going to be on the court with guys like this all the time. That’s the way I saw it. I knew everything about Doc. I was not going to let him go to the right or I would have been dunked on. You have to make him shoot a jumper from his left side. I scored 16 or 17 points. We beat them and I didn’t get dunked on.

|

|

BT: The last two years of your NBA career was with the Chicago Bulls. This was before the Bulls became a dynasty. What was it like playing with Michael Jordan?

Davis: At that time I was a true veteran. I had played against everybody and played against the best. It didn’t matter. I was just trying to see where I fit in. I had developed into a swing guy. I was kind of the Bulls enforcer at the time. Having to guard Michael and Scottie (Pippen) in practice for two years helped me. In a game, guarding anybody else was a joke. I played against anybody. I didn’t back down against anyone. One of my coaches said Davis was the only one that ever stood up to Michael and never backed down. That was my mentality. When I stood on the court I had to be competitive. And when we were off the court we were buddies. We played pool, joked around each other and did what guys do as teammates. When it came to game time, if Michael thought that the players on the court were not playing hard, he’d let you know. We were playing the Pistons in the playoffs and Michael said put Charles in. I never heard of a player telling a coach to put a player in a game.

BT: You had worn jersey No. 23 before you arrived in Chicago. Of course, that was Michael Jordan’s number. What was said about No. 23?

Davis: Every team I ever played for, even Vanderbilt, I wore No. 23. So before I went to Chicago I checked to see who was No. 23. I had been in the league for six years at the time. I walked into the Bulls locker room and Michael was on the training table getting taped. He said, `CD, don’t try it.’ I said, `What are you talking about?’ I knew we had to deal with it when I got there. I told him I could change the whole world if I wore No. 23. I said, `I’ll tell you what MJ. You pay me a half a million dollars, I’ll wear another number.’ Michael told me as long as I owed him a half a million, I’d never be broke. He still owes me a half a million bucks.

BT: Are NBA practices tough and intense?

Davis: It all depends on the coach and you as an individual to keep yourself in shape. You can play one-on-one or three-on-three after practice to stay in shape and keep your stamina up. When I played in San Antonio, we never ran plays. We just ran up and down and played basketball. When I was with the Bullets, everything was real structural. Our main thing was to get back on defense and be physical. Banging the whole time. When guys came off the screens loose, pop them and stand them up. With the Bulls we did a lot of transition up and down the court. It depended on the coach’s style of play. You’ve got guys that log a lot of minutes. The coaches are not going to have them out there the whole time running up and down banging too much. You are playing three games a week anyway.

BT: You did have an eight-year career in the NBA. That is longer than the average stay for an NBA player. What were your strengths that kept you in the league?

Davis: My longevity was that I could play three positions. I could play the big guard; the two guard and I could play some four. I was bigger and stronger than the average small forward coming into the league at the time. I was strong enough that I could bang to rebound with the power forwards. I was fast and could run the two guard and I could shoot. Don Nelsen (Milwaukee coach) said it was hard to cut me because I could play more than one position and could beat out some guy that has a guaranteed contract. He told my agent he couldn’t cut me because he didn’t want anybody else to get me and I was valuable as a swing guy and played three positions.

BT: What is a memorable experience playing in the NBA?

Davis: I was in a plane accident. Don Nelson, Mike Dunleavy and myself were taxiing on a plane to play Washington when I was with Milwaukee. On the runway, the plane set the brakes hard because there was gas truck on the side of the runway. The three of us had injuries. Nelson had to have surgery on his neck. I had occasional whiplash and Dunleavy, I think that his career. When I got back to the hotel room my whole left side just locked up. This is right before pre-game. I asked the trainer to apply some heat on my shoulder and neck. I played that night and scored 30-something points and was named game’s MVP. I knew all of Washington’s plays and their guys.

BT: What motivated you begin the Charles Davis Foundation?

Davis: There is more than athletics. You need an education to have a better life, to support your family and be a good citizen. That’s why I created the foundation. We are more of a resource-based foundation. I want to empower the youth to reach their potential which is through PEACE an acronym for Positive, Education, Athletic, Cultural, Economic development. We have programs to allow anyone with us or through us to progress. It is up to them. If you put in the hard work, it will pay off. I knew when I was out of shape. I would continue to practice even when basketball season was over. I applied that to my beliefs and foundation like we do today.

To learn more about the Charles Davis Foundation you can visit their web site at www.charlesdavisfoundation.org. If you have any comments or suggestions you can contact Bill Traughber via e-mail WLTraughber@aol.com.